"Security is a superstition. It does not exist in nature. Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing." ~ Helen Keller

The principle idea behind meteorologist Edward Lorenz's "Chaos Theory" speculates that the brief flutter of a butterfly's wings can evolve into air currents capable of creating a hurricane 10,000 miles away. Well, if you can believe it, her name really was "Fifi." She was 12 years old, just like me; and I thought she was beautiful.

Fifi... and Secrets

Years ago, my maternal grandparents swapped residences for a month with friends who lived on a small Greek island. Consequently, all involved parties enjoyed cheap, yet memorable vacations. The Hellenic friends got a cozy, three-story house in New England, while our family – grandparents, my mother and I, an aunt, an uncle, and two cousins – stayed at a minimalist, yet spacious former pistachio farm. I was bored and driven a little nuts by so many family members who were also bored. But as the undiagnosed kid on the spectrum who was enduring typical school pains back home, I also felt liberated, and grateful for such a dramatic change in scenery.

Fifi worked at the ticket window of her family's small movie theatre. And when I would walk or bike the two miles along the coast into town, Fifi could be seen on my right from the dirt road as it opened up onto the whole port. In the frame of my vision she existed as a bored, motionless oddity amidst a sea of activity; forced to sit in her tiny shed, surrounded by commerce – the unloading of small fishing boats, fast hands and loud voices in the open market, and on certain days, the sound of waves falling on the docks to my left.

Her English was broken, but good enough, and I set about my plan to ask her out on a date. In front of our bathroom mirror, I repeatedly tried to replicate the facial expressions Harrison Ford produced in the first Star Wars movie – contortions of the skin and muscles that magically elicited sounds of approval from the girls in the audience (…all twelve times I saw the movie). I'd never asked someone out before, but if I failed here, no one would know, so why not try?

When I arrived at the movie theatre, ready to ask, her much older brothers were doing some work in the back of the ticket booth. Clearly, it wasn't the perfect opportunity. "Eh," I thought, impatiently, "Big whup," and I went for it anyway. "Oh no," she blushed, smiling happily, "I am not supposed to go out with boys."

Halfway home on that dirt road her brothers ambushed me. They'd been running alongside, unseen by the foliage that shielded the ocean from the road's view, and so I never saw them until it was too late. They roughed me up a little, found a high point off land's end, and then as trees to my hammock swinging in the wind, they counted 1-2-3 and threw me into the sea. Walking home, soaked, but drying quickly in Greek summer heat, I was so happy. No, it hadn't been traumatic. Fighting was a way of life back then, and when I saw how deep the water was, I knew they had no intention to really hurt me. And no, it wasn't a happiness steeped in cultural pluralism by learning that Greek rules for dating were different – Please… the new rules sucked! And lastly no, I wasn't happy because I'd gotten nobly whipped up for a girl: while beautiful, Fifi wasn't worth this kind of trouble.

I was happy because of the marvelous discovery I'd made. I had just been humiliated, and yet I had the opportunity to keep it a secret. Had I suffered the same degradation back home, people would talk, word would get to friends, maybe family too, and I'd have to endure social repercussions for my failures until others got tired of teasing me. I might even be hearing taunts about it today! But because I was traveling, and having this experience amongst strangers, no one would know unless I decided to tell them. Far from home, in travel, there really was infinitely less punishment for screwing up. Herein, amongst strangers, risk, was relatively safe.

Risk, and the Entire Spectrum

Now if you're reading this and thinking, "Well, my child's place on the spectrum is much more challenged, so this article isn't really relevant to me," – you're making a huge mistake. For at its core, this story is about having a clean slate to try out new things, and this applies to the entire spectrum. My experiences are from my end of the spectrum (wherever you deem that to be) but the values are universal, and with modification can become adaptable to the entire spectrum.

When at home, everybody knows about the blowup you had last week, the issue you had in the produce aisle. Any time they want, caregivers can bring up the suspension you got from school two years ago. You're just waiting for them to do it, you know they know, and they know you know they know. You can't escape!

And if you make a mistake and get a lecture about it, this usually convinces you not to try again. Even if the lecture is deserved, why do people think that you'll have the social confidence to want to give it another shot? Where's the incentive? Is it to please your lecturers? Or to learn the lesson? Sociologist Terri Apter states that it takes five words of praise to erode the damage done by one word of blame. So those lectures, those emotional reactions from loved ones, only increase the humiliation.

But in travel, if you fall on your face in disgrace…who cares?

You'll probably never see those people again! Just go to the next (town, street, or store) and try again; only this time armed with more information with which to modify the social experiment.

As a school consultant, I know that when districts travel train the more challenged kids so that they can go learn how to buy a slice of pizza on their own…that on a developmental level this exchange is the victorious equal to someone like me learning to slow down movements and vocal patterns in the deep south so as to emulate locals (and have them accept me more).

But despite the wide-spread autism awareness we've all built over the last 20 years, our ability herein has actually decreased due to our urgency to monitor so much. Unless the individual is still learning not to inappropriately touch others, or doesn't understand street safety (i.e. that cars can kill you), I say they're ready for these independent lessons of travel. I'll be the first to tell you that we were way too reckless in my day. But I'll also counter that we've since gone way too far into the opposite extreme of over-protection, having bypassed an emotionally-healthy middle ground to the point where finding opportunities to develop confidence and strength, wherein you are truly unmonitored, have become far harder than they need to be.

We also often teach independence by…increasing their dependence on us as caregivers? And we wonder why it's not working? Independence, outside of cooking, cleaning, and how to manage a bank balance, is often best taught by independence itself.

Our over-protection has humanist origins. Spectrum realities such as pool drownings, assaults of every kind, and a sickening overuse of the sex offender registry have so riled up caregivers that spectrum kids are often raised in a fear-based atmosphere that resembles a lockdown. But I believe that we, as spectrumfolk, process failures better than people think. I think caregivers refrain from providing true opportunities at independence often because of their inability – not ours – to process the failures. It's a snowball effect, leading to spectrumfolk being denied the opportunities to fail, which then makes for true inabilities to process failure because failure itself is now so much more intimidating. Under these circumstances it can even transform into trauma. Our kids leaving home successfully means relying on us as parents less, not more (and as I wrote in my first book, nervous parents usually end up raising nervous kids).

The degree of independence will always be relative to one's place on the spectrum. But if we all digest these ideas, then we might do a better job of looking for those proportionally-appropriate situations amongst "strangers" – You know them… those fellow earthlings that we've been condemning as too dangerous to interact with?

My mother and grandparents did not monitor me when I went into town on that dirt road, or when I'd be gone for hours. Therefore, my capacity for adventure, and my confidence in risktaking, was comparatively through the roof. All my attention could now be directed at the world, rather than apportioning off attention to the amenable, or unwanted companion that most kids on the spectrum are stuck with when they're out amongst the community.

What we can do as parents is to let go of control, not try to assume more of it as is our instinct – to be the catalysts of independence, not the architects. If we can't stop ourselves as parents from monitoring, we could at least convince kids of the giant lie that we are completely unaware of whatever transpired. Is there more risk? Yes. Is it worth it? When you consider the true cost of doing otherwise? (the absence of confidence? Or Independence?) Absolutely.

Becoming That Pluralist

Another benefit of travel for especially the literal-minded spectrumite, is that you become a pluralist; one who gets it into their head that there is never one way to do anything. And immersing yourself in different customs and traditions is incredibly helpful because as spectrumites, we often desire the narrow-minded simplicity of one culture; we often don't want more than one option, as we don't trust our ability to choose! (It's like trying to shop at a large supermarket when you're really hungry). Issues without context are easier to count on, and therein become safety valves to those of us who find ourselves in a very strange world.

Oddly enough, many economically-challenged children learn this lesson much faster than more-privileged folks, and here's how. When we grow up, our parents convey their values to us, usually in the context that this is the way to live life on planet Earth. Most of the time we comply and emulate them – until later on when we realize that our generation is rejecting or reshaping those values… into new standards that the younger generation can call its own.

But often, poorer children get partially or even fully raised by grandparents, who have different values than the parents. And not only do those kids therein learn early that there is a different way of thinking than that of their parents, it opens up the opportunity to sense that there could be multiple ways of thinking. When my father left for Vietnam, my mother and I moved in with my grandparents so that my mother could try to get her degree. After my father's death, we continued to live with them, and even after getting our own place, they were a mile away, and always retained a major influence. I clearly saw differences in the values of my 1960s-era mother vs. the more Victorian mores of my grandparents.

Travel exposes you to what those different modes of thinking, interpreting, behaving, and feeling…really are. And this gives you options, starting with the choice to embrace those elements that you like about the culture you grew up in, and to reject the ones that you don't.

"Oh, He's Just Weird Because He's a Foreigner."

Where travel does discriminate between the entire autism spectrum is that some of us have varied abilities to conceal our diagnoses, and some of us have none.

Still, more of us have that ability abroad than we do at home. For when are a foreigner, you are expected to be different. A little struggle with eye contact won't be noticed that heavily, and in countries that speak a different language, a unique and monotone manner of speech will rarely be of concern. Even the occasional inappropriate comment can often be misinterpreted as having been translated awkwardly.

Where you may not be ready for travel is if you are so infused with the spectrum tendency to be self-involved. For everyone wants to be heard, and any natural interest in that other culture will go a long way towards their embracing you. But be forewarned: real attention to other people and their stories is almost impossible to fake.

If you can show that true interest in their culture, then not only will this increase your chances for acceptance abroad, there is the additional benefit that it could make you more attractive at home to foreigners in your country.

As the relatively "weird" person in our surroundings, our sense of alienation from our peers will often be noticed by others. And to visitors and immigrants who are also trying to figure things out, this then presents as a potential bonding mechanism. They're more prone to share their sense of estrangement if they see that the majorities are alienating you (however unconsciously), and they do so in the hope that you might understand what they're going through. For instance, when I was in college, all of my longer-term relationships were with girls from France, Sweden…etc. Fellow spectrumite author, Stephen Shore, married a woman who is originally from China. The "not belonging" factor can make for kindred spirits that metamorphasize into…belonging. I didn't marry a foreigner but my wife and I met in Iraq, and I wonder if she would have fallen for me under domestic circumstances. Over there, I know that I was at my passionate best, and that others more universally respected me. I wasn't the eccentric guy in Iraq, I was the guy saving lives.

And if you fall deeply in love with being far from "home," well…many spectrumfolk also live happily abroad.

"What Doesn't Travel Accomplish for People on the Spectrum?"

While the following is an admittedly superficial and paraphrased rendering (I'd bore you otherwise), the criteria for an autism diagnosis under the DSM-5 comprises three major points:

1. Deficits in social communication In travel: People care less.

2. Repetitive patterns of behavior In travel: People care less.

3. Symptoms must present in early childhood.

In travel: People care less. And no one knew you then anyway. If one is young and has a speech delay, therein perhaps avoid travel to a country where English is not well known, as learning new words could hamper the development of your first language. But if you're secure in your native tongue, travel. And remember that the less they speak your language, the more you will learn of theirs.

If you have potentially alienating issues, such as with hygiene… that you do not address because you want to be liked for who you are, try to at least accept that others have the right not to want to spend time with you, and that maybe you too are not ready for travel abroad.

We are a part of a minority that cannot yet "just be ourselves" and be accepted. In order not to slip through the cracks we have to make ourselves into somebody that others will take interest in. This can mean working hard at a talent, like a musical instrument, or a language, or any ability that will cause others to notice us. But in the end, everyone (including neurotypicals) has to become someone that others will want to befriend, date, or hire. Nobody can just really "be" unless they are ok with limiting their potential friends and partners to others who also just want to "be," or to not developing.

go Ahead… Hit Me with your Excuses

Actually, don't. Because the only legitimate excuses are a medical inability to leave home (which is probably insurmountable), or a lack of money. On the latter, let's think… One golden rule to remember is that the more exotic your destination, the more likely the exchange rate will dramatically work in your favor as an American. That right there is an economic winwin. If you're a parent, try the house swap as my grandparents did, and save perhaps thousands of dollars in hotels. Such swaps, thanks to the internet, shouldn't be that difficult.

Some Examples from Bygone Days

In 1986, I spent months behind the Iron Curtain. Finishing my undergrad work at Hampshire College, I had become a rather junior scholar of a World War II era playwright named Bertolt Brecht; and with the help of a college advisor got permission from the East German government to do some work in the Brecht Archives in East Berlin. Well, thanks to the exchange rate, I lived in a land that no Americans were traveling to on less than $5 a day. I had saved money from my job in the school cafeteria and took off for, not just East Germany, but also Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary.

My graduate writing thesis for Columbia University required that I live out of my car for the summer of 1988. While I needed starter money to figure out how to get work to pay for food and gas (and beer), I soon got the hang of it using a CB radio, and by inquiring at truck stops. I worked every job imaginable; road crews, open-pit mining, car mechanic, dish washing, unloading trucks, I was always paid at the end of the day, and in cash. In sticking with small towns (where you will always be noticed), I frequently cut deals for free beer by playing guitar in bars. Compared to what my needs were as a 23-year old (such as $5 per night or less to pitch my tent), I was actually rolling in money. On that trip, I accrued independence and job skills that went far beyond the provincial lessons experienced by my neurotypical peers. The rules have probably changed, but… go learn the new rules!

Any chance I could, whether it was with family, a group of friends (for some strange reason I had a lot of buddies who were well-known combat photojournalists), I left, to adventure with them. And while I never made much money, I could sometimes get my expenses paid by writing about the experience, such as when I covered the Jamaican elections in 1989. If a big event is happening that's worthy of global news coverage, there will at least be foreign media representatives there that you can solicit.

And if you can dream of getting so lucky, your adventures might become of value to someone, and become a job. Unlike my friends and wife, I did not become a proper journalist. But as the United Nations Representative to a veterans group, I conducted work in Cuba, Bosnia, and was the Director of the Iraq Water Project (IWP) an endeavor that brought clean water to 81,000 people in the Basrah area during the Saddam years. In those days, when I said something inappropriate to a boss, I got away with it so much more than I would have in an office job because the work was somewhat imperative. Getting the job done in that line of work was a lot more important than how it got done. My advice for the adventurers of today (whose spectrum "juice" resembles mine) would be to scale back on some of the risks I took, like… avoid bullets. And maybe avoid countries that harbor the Al Quaedas, the Talibans, and the Boko Harems. Avoid North Korea too. I know they're in the news a lot, but given their monitoring system, you'll unfortunately learn very little. Think instead of places like Belarus, all the other countries in Africa, spend a month or six in India, Bolivia, China, or better yet… Iran!

Tabula Rasa

Far away from home, no one was expecting "weird," "smart," or "rude" Michael John to say or do something out of the ordinary. Our home life, after all, is dependent on how others interpret our past behaviors – how our words and deeds become the building blocks of our reputations. Our happiness at home relies much on other people's opinions. We are treated differently because of earlier actions – sometimes suffering, sometimes benefiting from the consequences.

But not so when we are strangers with no history. With unfamiliar people we start from scratch. Amidst unknown territory, the treatment towards us is clearly different. Herein freed, we can conduct tests, trying out different mannerisms, or different ways of carrying and presenting ourselves without fear of reprimand or ridicule, because no one besides us knows that we are faking something. In travel, our successes in behavior modification come quicker because others unknowingly give us a superior chance to learn.

Sometimes the risks are painful. When I arrived in East Berlin at the end of my 1986 trip, I was not well. Having run afoul of authorities who wanted me to sleep in expensive hotels rather than youth hostels, I'd spent an awful lot of nights running from cops, sleeping in train stations or park bushes (a night in jail) – and I'd recently been violently sick with one of those 24 hour illnesses. After months in the other countries I was near tears as I would plead with officials for the "Eastern-Europeansonly" hostels that to my surprise barred Westerners (the other communist countries had no issue with my staying in their hostels). I begged them to let me in… just to have a bath even… until finally, one succumbed. I rejoiced like never before, and may have cried some from relief. My long shower preceded a 14 hour sleep. And so happy, I did something in waking that in today's context won't be viewed so favorably – I passionately kissed the maid; though not because I wanted anything else to transpire. I did it to show "Anja" how grateful I was to everyone there. (After doing it I of course wondered if I had gone too far, but she eased my conscience by demanding my address in the U.S., and yes, I got a few letters later on).

And two years later, in living out of my car in the states I was cathartically confronting the land that I felt hated me, and that had stolen my father. Still three years away from quitting drinking, there were a lot of bar fights – most of which I lost. But herein I was just as much the prized foreigner as anywhere else. That trip taught me that most of my country was surprisingly just as, if not more eccentric than me, and that it was home, whether I liked it or not.

I could go on… But the real mystery was as follows: That for as long as I can remember within these fantastical travels, that I've had an intangible, remarkably overblown sense of purpose; a narcotic illusion of destiny egged on by the ideas I studied – theoretics foretelling me (and others, as this is a very spectrumlike tendency) that great heroism was in store; even as it told others, rather accurately, that great comedy was a lot more likely.

But that's what makes it so much fun. That's why travel teaches you to take yourself less seriously, not more. That's why, at my age now, these experiences are money in the bank; withdrawals, rich with interest, that I can extract at any time, whenever I need a voice telling me how lucky I am.

Midwesterners Have no Sea to Look At

When I went downstairs at the East German hostel, there were four women waiting behind the check-in desk. Dressed in their hostel employee uniforms that included (surprisingly) stylish red coats, they beamed at me and erupted into laughter.

"You kissed Anja, yes?", one asked. Embarrassed, I smiled, laughed also, and nodded. Gesturing to her colleagues, who all smiled at me, she said, "Then you have to kiss all of us."

I know, I know… in this day and age that may not be the best story to tell. But given that informed consent was loud and clear, I share it.

It is also a moment that still resonates with intense, shared joy. I can only speak for myself, but I'd wager that none of us had sex on the brain at all. As I did indeed kiss all four of them, warmly amidst a sea of blushing and laughter, I knew that we were enjoying the kind of moment you can only have with someone that you will never see again. The word is "abandon." We have forgotten that it also has a positive use.

My mother only put her foot down with me twice. The first time was in my senior year of high school when I wanted to go to Oberlin music school. She refused, saying I was going to a liberal arts school. The second time came at the end of my cross-country trip, when I was fully intoxicated with a confidence I was sure no one else had ever known. I could get work anywhere, and I could meet new people for as long as I wanted. In a phone call, as I regaled her with a monologue depicting my superiority over the rest of the world, she surprised me by interrupting. "You need to come home."

It was like the snapping of fingers that releases you from the grip of hypnosis. Eventually back in Chairman Howard Stein's office, I feared serious reprimand. I was supposed to have arrived at Columbia to begin my thesis year on September 1st. It was now October 3rd. "Michael, did you seriously entertain not coming back?" I remained silent. "You were thinking of staying out there, and living like that…?" I nodded, and I wasn't smiling. But he was.

Where I come from, even the poorest of the poor are encouraged to dream about the faraway places they hope to visit.

But we recently moved to the predominantly white, northern Midwest to take care of in-laws. Because we did so for family, we'll never regret it. But it's been really hard – and not just because of the contrast that 28 years of prior New York City living would indicate. The Midwest is now an incubator of insecurity, resentment, and low-productivity. Whereas it once enjoyed a rich, educational history, thriving industry, and a dedication to community and toughness (both mental and physical), it has slipped into an Emperor with no clothes – one that cannot face its lack of an economic or spiritual future. Forget diversity – real critical thinking is also rejected at the first, subconscious sign (too intimidating). White values herein are such presumed universal values that locals can't understand why people of color aren't flocking to adopt them. Here, the good folks refuse to stand up to the bad folks, which puts into question how good they really are. Perhaps all are threatened by our coastal standards (including the pressure to travel), as they seem to demand that we stop judging them in reference to our snooty selves. With apologies to the ones I care about, they insist on their right to what I have termed "the license to suck (at whatever they do)," and will not stop whining until we give it to them.

And so, within this region, feeling as rejected as I was in middle school for my behavioral differences (and corresponding big mouth), I remember stories like those I've described in this article more vividly because it has become critical to do so; not to combat Midwesterners' accusations of elitism, or their cultural reluctance to venture outside their own skin – but instead for me to make sure that I continue to share with them, even if it's in the disrespectful spirit of colonialism. They too often seem indignant that others have stories to tell, choosing to believe that the only reason people tell them is to make others feel inferior. Their lack of confidence is heartbreaking, but their dedication to isolationism is sickening. So every time I venture back East, I rush into the love of friends; figuratively bathing in both their approval and the absence of behavioral bigotry. But I also reserve one morning to stand on a beach.

I imagine what lies afar – not because I can visualize it, thanks to the travels that shaped me; but instead because the conjuring act serves as a challenging, albeit beatific reminder that at heart, we are not free; not one bit. The bitterness of Midwesterners is a poker tell; it's a dead giveaway. Somewhere inside, they know what they're missing. Unless we all expand with our fellow man, and grow past our surroundings, we are prisoners.

When you're that kid on the spectrum, diagnosed or not, you get it – that others don't get you. I knew, walking home on that Greek dirt road, that if I were to tell my family the story of Fifi and her brothers, that they would come up with inaccurate assessments and irrational, unthought-out takeaways; all of which they'd of course have to "share." Trust me, there would be plenty in my life that I would not share with them. We'd all been down this road many times before. But their forever-unconditional love always more than made up for the confusion, and said love felt strong that day. So I told them what had happened. It was my choice. And I am still hearing jokes about Fifi to this day. It has never bothered me.•

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Michael John Carley is the Founder of GRASP, a School Consultant, and the author of Asperger's From the Inside-Out (Penguin/Perigee 2008), Unemployed on the Autism Spectrum, (Jessica Kingsley Publishers 2016), the upcoming Book of Happy, Positive, and Confident Sex for Adults on the Autism Spectrum…and Beyond!, and the column, "Autism Without Fear," which for four years ran with the Huffington Post and will soon be transferred to Sinkhole at sinkholemag.com For more information on Michael John, or to subscribe to his updates, you can go to michaeljohncarley.com

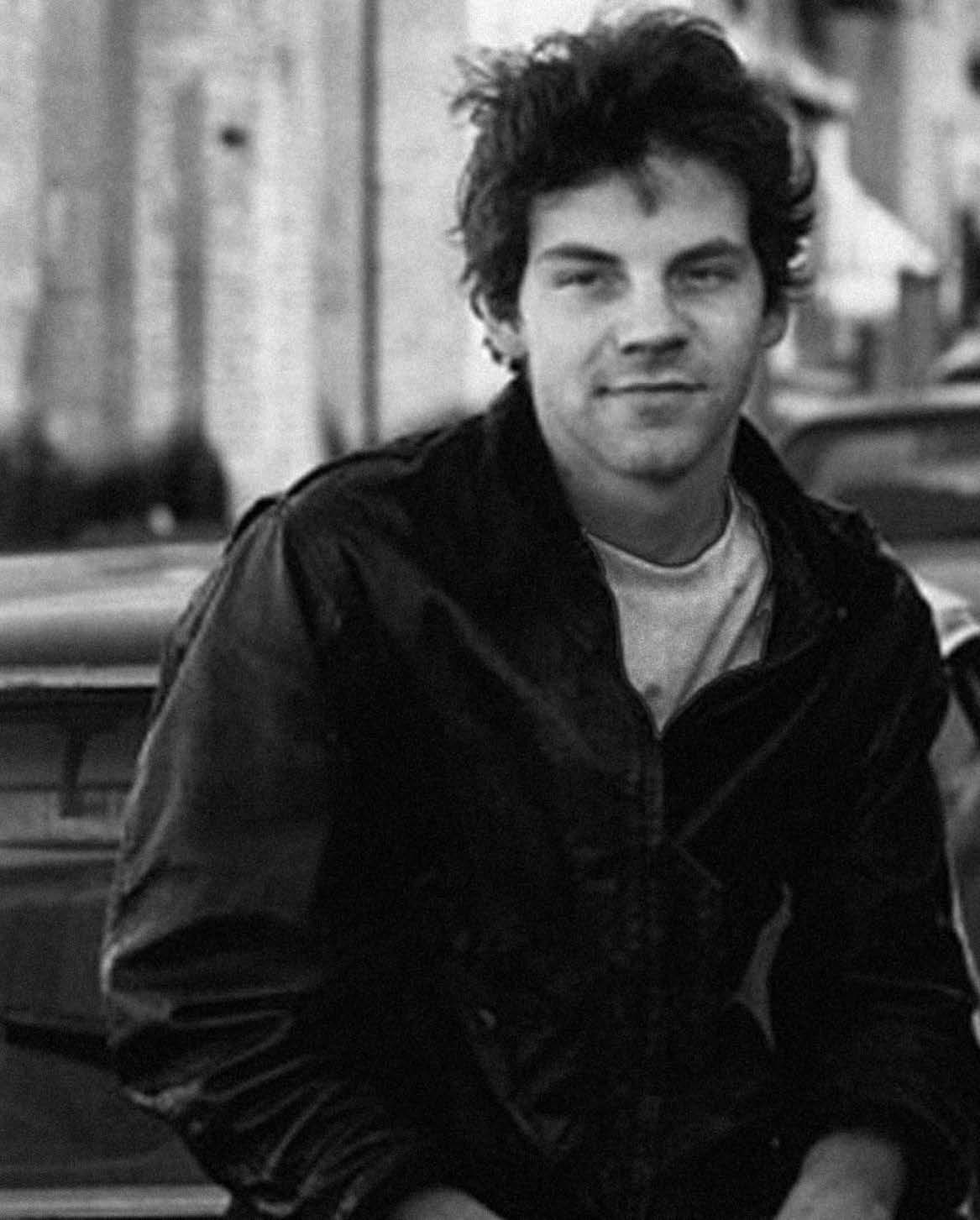

SOJOURNER: Michael John Carley during his months inside Eastern Europe, 1986. "In travel, our successes in behavior modification come quicker because others unknowingly give us a superior chance to learn."

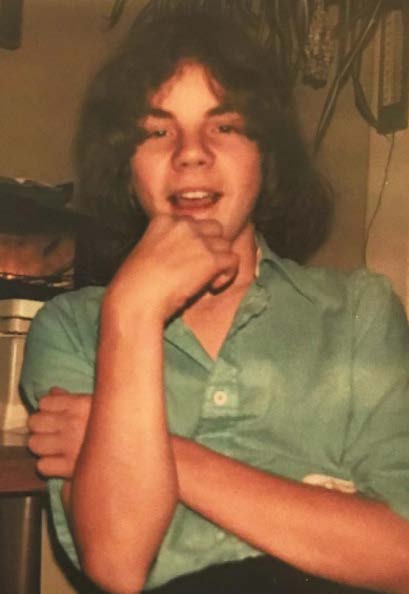

CHARTING A COURSE: (Above left) The author at the age of 12 or 13, around the time of "Fifi." (Above right) Later, as a teenager; learning to read maps and look afar.

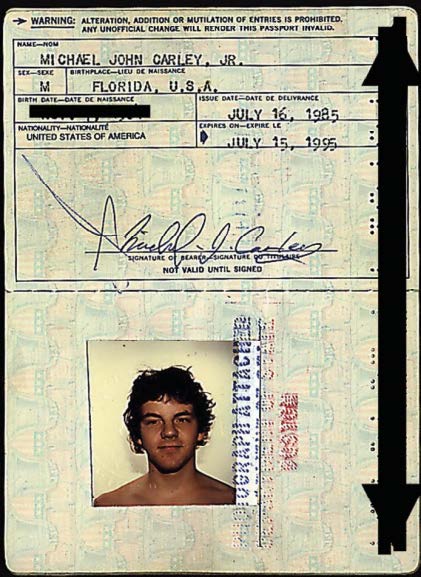

QUICK PIC: The author was washing pots at a kitchen job one summer when he realized he had only one hour to get a picture taken and mail in an application for a new passport. Needless to say, this provided many border agents with a good laugh.

READ ALL ABOUT IT: A 1996 Sarajevo newspaper article details the author's work with veterans in Bosnia.

THIRST FOR ADVENTURE: With neighborhood children in Iraq at the restored Labbani water treatment center in 2001.