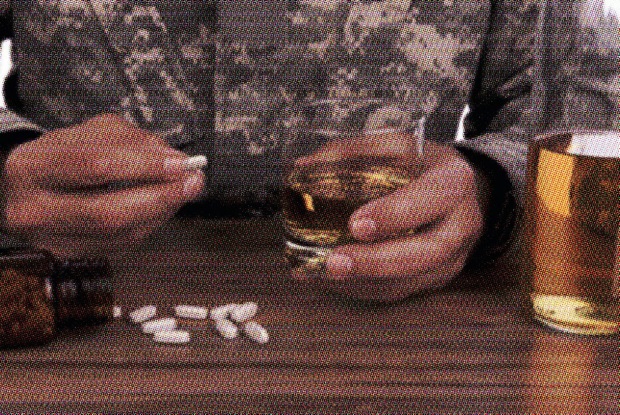

Some veterans shared that they feel as if they are bad in some way, and that is why they are taking drugs and alcohol. They seem resigned to the notion that they are not worthy of feeling good about themselves. Face it, waking up after a night of bingeing and/or drug use is not a good feeling. One is not going to wake up singing, "Oh, what a beautiful morning!" Many have said to me that to attempt to allay the urge for drugs, they imagine what they will feel like about 12 hours from the beginning of taking them, in hopes of being deterred. Generally, they will succumb to the urge, because the pull for that feeling of relief is stronger than the deterrent of a hangover the next day. It's those 12 hours that the servicemember is after, a way to relieve the pain. What do I mean by relief? Feeling better. A way to escape feeling depressed, anxious, or half alive, as one military member described. The problem is that this relief is so very temporary and, even worse, can prove fatal. Where can a servicemember find a form of healthy relief? Therapy is a good start. Unfortunately, some express their fear of opening up with anyone, afraid that their history would not remain confidential. There is a feeling of loss of safety after having been through some very scary, life-and-death events. Feeling trust in anyone or anything in a world that no longer feels safe is a very difficult hurdle to overcome. There is a loss of faith not only in themselves but in the world at large.

If you can relate to this, do not give up on finding a practitioner or friend that you can trust to share your experiences with, since this is not a problem that is conquerable alone. The desire for relief from the pain born out of traumatic experiences is a very strong one. One veteran said that he

grapples with the desire to turn to drugs or alcohol. What occurred to me as he said this is that one needs to get in touch with what is driving the actions toward this destructive behavior. Before healing can occur, he or she will have to take a long, hard look at the traumatic

event and its aftermath.

Fear is a mighty foe. There is fear of facing the past, fear of remembering the acts from combat, and fear of facing a personal sense of guilt for these acts. Self-medication is a way of escaping from fear and shame. The problem is that this form of escape not only creates more

shame, but can put a person's life in jeopardy. In speaking with veterans, I found that several of them were not moved by the idea of losing their lives while taking drugs. They had seen close friends, comrades, the enemy, and innocent civilians die, and they were numb to the desire to live as a result. They seemed to be living in and out of their bodies. In therapeutic

terms, they were dissociating.

"No matter how low you think you have sunk into an abyss, there is hope. At the root of all of this pain is a crisis of faith. I do not mean faith born only of religion, but faith whose root lives in a person's innermost, private being – the faith that produces the momentum to believe that life can be meaningful again."

Dissociation is a very self-protective act, a form of defense, to dissociate oneself from feelings that were generated by a traumatic event. Unfortunately, war is a source of traumatic events. Dissociating is a way for one's psyche to protect itself from experiencing feelings of sorrow and pain. The double-edged quality of this defense is that it leaves a person unable to experience real joy as well.

In an attempt to survive, the ability to thrive has been thwarted. One becomes like a vessel floating emptily, aimlessly, uncertain of the past and very disconnected from the future. The present is what one is attempting to endure. event and its aftermath. Fear is a mighty foe. There is fear of facing the past, fear of remembering the acts from combat, and fear of facing a personal sense of guilt for these acts. Self-medication is a way of escaping from fear and shame. The problem is that this form of escape not only creates more "No matter how low you think you have sunk into an abyss, there is hope. At the root of all of this pain is a crisis of faith. I do not mean faith born only of religion, but faith whose root lives in a person's innermost, private being – the faith that produces the momentum to believe that life can be meaningful again." shame, but can put a person's life in jeopardy. In speaking with veterans, I found that several of them were not moved by the idea of losing their lives while taking drugs. They had seen close friends, comrades, the enemy, and innocent civilians die, and they were numb to the desire to live as a result. They seemed to be living in and out of their bodies. In therapeutic And the quest for the high, the quest for numbness, is a way to avoid feeling pain, an attempt to experience a synthetic form of joy or elation. It is not the kind of joy one feels when he or she sees a loved one accomplish a milestone in their lives (e.g., seeing a son or daughter graduate from college, or an elder parent reach age 80, or the feeling of joy one feels when he or she falls in love). It is a very temporary feeling of elation. As I've heard it described, "I felt amazing, although it was short-lived." Where is the future in that short-lived feeling? There is none. It is hollow. So how does one shed the pain, be alive again in a real way? How does one learn how to create and experience real joy? How can one avoid being paralyzed by the pain of the past? No matter how low you think you have sunk into an abyss, there is hope. At the root of all of this pain is a crisis of faith. I do not mean faith born only of religion, but faith whose root lives in a person's innermost, private being – the faith that produces the momentum to believe that life can be meaningful again. To do this, one must investigate the pain born out of past traumatic experiences that led to