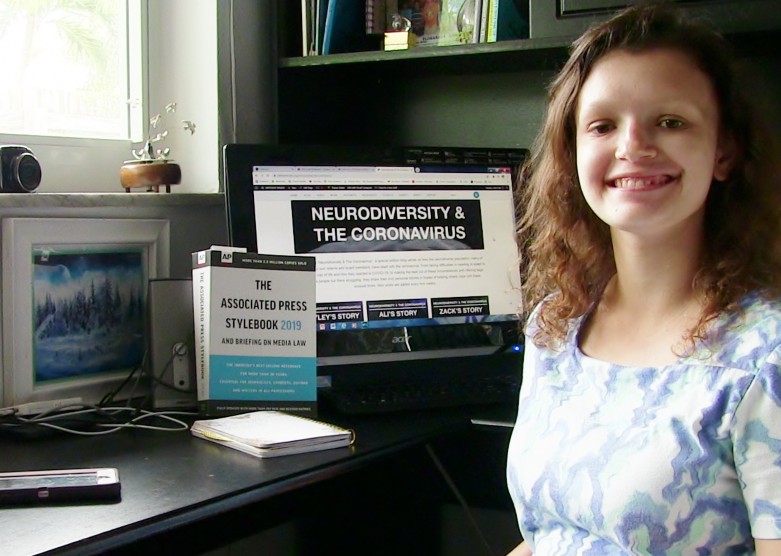

WRITE AWAY: Julia today; "From working in the office of Different Brains as a camera person and a writer to working at home on my Neurodiversity and the Coronavirus project, I've really enjoyed being a part of their internship program. It's given me the opportunity to advocate on the behalf of myself and others."

Being a neurodiverse advocate

BY JULIA FUTO

It's important for someone who is neurodivergent to be able to know how to stand up for themselves, but so is knowing how to help them when they need it the most. This is for the educators, employers, co-workers, caregivers, parents, friends, and family members out there.

The word "advocate" can be defined in many ways. An advocate can be a person who publicly supports a particular cause or policy, defends or maintains a cause, or promotes the interests of some kind of group. A self-advocate, on the other hand, is someone who represents themselves or their views and interests. They strive to help others with the same views and interests as their own. Advocacy is crucial, but how does one become a good self-advocate? The best way for me to explain this would be through my own personal experiences and how they helped me become the person I am today.

My journey began the day I was born. Although my mom's pregnancy with me was uneventful, I was extracted with a pump because I was in distress. My shoulder was stuck, the cord was wrapped around my shoulder and neck, and there was a true knot in my umbilical cord. We also learned my umbilical cord was connected to the placenta abnormally (velamentous cord insertion). I was born blue with Apgar scores of 5/8. My first blood test results came back atypical for 18 of the 31 results. I also had jaundice and went home with a light for three weeks. My mom's delivery nurse called me a "miracle baby" and told my mom I was born for a reason.

I was my parents' first child. My mother's family lived in New York, and we lived in Florida. My mom, having no experience with babies, thought I was a "high need baby" as was described in her "What to Expect the First Year" book, so she followed the directions and attended to my needs, not knowing what a "regular need baby" was like. Her mom was an elementary school teacher and she noticed things about me that were different before I was one year old. My grandmother enlisted my aunt to help. My aunt is a speech pathologist in an elementary school. My aunt arranged a developmental screening for me when I was three years old, which recommended further evaluations.

To compound problems, my eyes started to cross, and after months of alternate eye patching with no success, I had double strabismus eye surgery a few months after my fourth birthday. My depth perception has always been impaired because my eyes don't converge. I failed every school eye test, so I get notes from the eye doctor's office after testing one eye at a time to pass. Besides being uncoordinated, the lack of depth perception made me trip over curbs and walk over the ends of playground equipment. I frequently injured myself by accident.

In kindergarten, I underwent a professional evaluation by a respected neurologist at the Dan Marino Center. I was diagnosed with encephalopathy, which is a fancy way of saying, "brain damage", and developmental coordination disorder (DCD), also called "dyspraxia". DCD is both a physical and developmental disorder that impacts the ability to learn motor skills and coordination, things many people take for granted. DCD can also impact learning ability. For me, it affected my coordination, balance, motor skills, knowing where my body was in space, and because it's a developmental delay, I was always behind in everything. I also started physical and occupational therapy.

I struggled a lot in kindergarten. Little things were constant challenges, like keeping my pencil from rolling off my desk. I was given a desk in kindergarten that had a sloped top instead of a flat surface, which didn't fit with the flat-table groups the rest of the kids had. I also had assistance from a classroom aide at my desk, and as a result, I didn't sit in the circle to learn the teacher's lesson or instructions. I didn't sit with my peers, so I was isolated. I stood out, not in a good way. As a little kid with disabilities, I didn't know how to advocate for myself, or even that I needed to.

As part of the Exceptional Student Education process, I was evaluated by the school at the end of kindergarten to determine my "placement" and to develop an Individual Education Plan (IEP). A school psychologist evaluated me for my first-ever IEP during recess, where she observed me sitting by myself under the playground slide. I actually sat there on purpose because the playground was set up within an interior courtyard. All the kids played dodgeball and the balls would, for me, unpredictably ricochet off the walls throughout recess. I wasn't able to judge how to stay out of the way, so the balls frequently hit me. The other kids laughed when I got hit. I liked neither the pain nor embarrassment of recess, and felt safe under the playground equipment since the balls couldn't hit me there. The school psychologist never bothered to ask me why I hid under the playground equipment, and I would have told her it felt safe. In her report, the psychologist declared my behavior as anti-social, and I was diagnosed with autism. My school IEP placement labels were autism and OHI (Other Health Impaired), to include the DCD.

When I was eight, I had a language evaluation, which resulted in a vestibular (balance) evaluation, and additional therapy to integrate my primitive reflexes. I was in third grade with retained primitive reflexes. This was very unusual because primitive reflexes are supposed to be gone at three to four months of age. I spent an entire summer, five days a week, with physical and occupational therapists trying to integrate them, but to this day, I still have some, and they cause me to always feel on edge. I was also diagnosed with nonverbal learning disorder.

When I was ten years old, my mom enrolled me in a type of Japanese martial arts called "aikido", which helped me in so many ways. Not only was I learning martial arts, I became stronger physically, mentally, and emotionally. The people at Aikido accepted me unconditionally, which significantly improved my development, social skills, confidence, and self-esteem.

The beginning of high school was tough! I was enrolled in a technical high school for my first two years and the pace was too quick for me. I also felt very lonely. I didn't belong there, so it was time for a change, and I'm glad I did because it led to a breakthrough.

I transferred to my home high school my junior year, and one of the classes I had to take was journalism. My journalism teacher took notice of me early on—not because I was "different", but because of my writing skills, work ethic, interest in photography and videography, and because I got things done on time. Instead of making me stand out in a bad way, he saw my strengths and helped me enhance them. He saw potential in me and went out of his way to help me succeed, which is something no teacher had ever done for me before.

The next year, he became my yearbook teacher and gave me the role of copy editor. However, I wasn't limited to that one job. I attended school events as a camera person and had to go interview people, which was the first time I did "extra-curricular" activities at school. My ESE facilitator noticed my involvement in school and asked me to give an informative speech on my overall ESE experience to a group of Caribbean school officials visiting our school to learn about exceptional student programs. I had never done anything like this before, so I had no idea how it would go, but it went so well, I ended up giving a few more speeches before I graduated—one of which was at a faculty meeting. This was huge because no student in my school had ever attended a faculty meeting to be a guest speaker and teach the teachers something. I also gave a speech about kindness at the Senior Class Award banquet, and received a standing ovation. My ESE facilitator and yearbook teacher helped transform me from being a nobody into a somebody with a strong voice.

AGES AND STAGES: (clockwise from top left) "As a baby, I had an elongated head since I had to be pulled out with a vacuum. My family likes to joke around about the shape of my head, and they think it looked like a tic tac;" "Here I am at nine years old. I spent this summer doing physical and occupational therapy every day to integrate my primitive reflexes. My dog, Ting Ting, made me very happy; "My kindergarten school picture. My face has a few scratches on it because I am clumsy. This is also about one year after my double eye surgery, and my eyes are still a little crossed."

At aikido, I learned I was powerful, but I didn't know how powerful I was until I got up in front of a large group of people, shared my life story with them, and offered them advice on how to help someone who is neurodiverse. It was a beautiful stage of my life that I will never forget and will always cherish. This is how I became an advocate; now it's time for me to share with you the lessons I've learned and how to be a self-advocate.

The first step for me was self-acceptance. If you have difficulties accepting who you are as a person, you may be left with low

self-esteem and try to be someone you're not, which makes functioning in life even harder. At first, having a diagnosis can be scary, and then you may deal with the thoughts of "something is wrong with me," but know you are more than your label(s). Just because you are a little different, it doesn't mean you are incapable of accomplishing anything. In fact, neurodiverse people are often extremely gifted in areas that the neurotypical population would find unfathomable.

Upon recognizing you do have strengths and knowing what they are, you can be a force to be reckoned with! Because I'm a little slower than average, I have been told by many I have the patience of a saint. I've used this patience to not be judgmental of others, which, in one case, was even lifesaving to one of my friends who had depression and considered suicide. I listened to all of her problems and let her know I was there for her. She felt accepted, and that's all she needed. I then learned my patience was helpful to others. When you hone your skills and find something you're passionate about, the rest is a walk in the park. This is where you want to start, because you'll then be able to find your voice.

Upon having a passion about something and finding your voice, you'll have what you need to start an advocacy role. To find your voice, it's important to have confidence in yourself and be able to set boundaries with yourself, others, and organizations. If you aren't getting the help you need, but you also don't stand up for yourself, you may never get the help. Sometimes, you'll need to be the one to take initiative to help yourself or others, and when you do, it feels very rewarding.

Sometimes, we need help finding our voices, and that's where having connections to the right people helps. Several people and groups have helped me develop into the advocate I am in different ways, but I had to ask for help first. Although it can be difficult to ask for help, there's no shame in doing so. By asking for help, you are advocating for yourself. These people and groups would ideally have your best interest in mind, and like my ESE facilitator and journalism teacher, they'd have the ability to see the best in you and help you bring out your strengths.

Finding a platform helps too. I enjoyed giving speeches in high school so much, I didn't want it to end upon graduating, and I was in luck. One of my aikido teachers introduced me to an internship program at DifferentBrains.org, a non-profit organization that helps the neurodiverse population become advocates through journalism. She knew one of the board members, who knew the founder, and forwarded me an email detailing their internship program. I'm so glad I joined, because through Different Brains, I've met people from many different walks of life and of various professions.

Introducing interns to professionals in different fields is part of what they do there. At Different Brains, I've created various blogs ranging from my own experiences with DCD, to making an entire coronavirus and neurodiversity project, where I give other neurodivergent interns the opportunity to tell their stories as well as offer advice to people having a hard time dealing with COVID-19.

Different Brains interns are provided with one-on-one attention and they have the ability to work with, and learn from other self-advocates. I've gotten more support from Different Brains than I've gotten from almost any other agency and I get to do what I love, so finding this platform was a win-win situation for me.

It's important for someone who is neuro-divergent to be able to know how to stand up for themselves, but so is knowing how to help them when they need it the most. This is for the educators, employers, co-workers, caregivers, parents, friends, and family members out there. Here are some of the things people have done for me that have worked and may be able to help you help someone who is neurodiverse.

Spend time to get to know us on a personal level. You never know what has happened to us behind closed doors, what struggles we've been through, and how our experiences further affect how we behave; ask questions like why they might be sitting under a slide at recess, the answers might surprise you. By getting to know us and not stereotyping us, you are earning our trust and we can start opening up to you. You may also be able to find our strengths and help us work on them.

Communicate amongst each other about our progress. It takes a village to raise a single person, but how can the village help if they're not communicating with each other and don't know how we're doing?

Communication with someone who is neurodiverse through encouragement, positive reinforcement, confidence building, and in my case, candy corn (I would do anything at school for a piece of candy corn), can be the teamwork that makes the dream work! Also, we need to be around people we do well with, as being with mismatched teachers can cause us a lot of damage, and exacerbate our delays. Patience with us is key, as it may take us a little longer to learn or comprehend something, but it is well worth it in the end.

In the words of Francis of Assisi, "Start by doing what's necessary; then do what's possible; and suddenly, you are doing the impossible." In life, we all face adversity, but we become stronger and better human beings as a result of it. This rings true especially for the life of an advocate and someone that is neurodiverse. Light shines the brightest during the darkest of times, and during these times, we begin to discover who we truly are as well as the power we have. Our biggest weaknesses can oftentimes be our greatest strengths. •

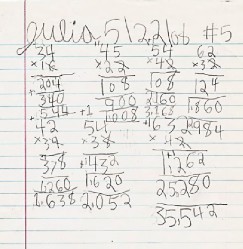

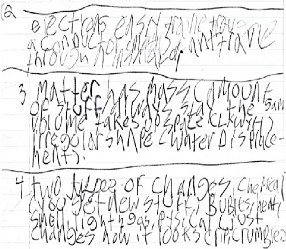

DEVELOPING DISCIPLINE: (clockwise from top left) "Trying to do assignments and homework as a little kid was tough. I couldn't even read my own handwriting so studying for tests from my own notes was impossible!;" "I started aikido as a ten-year-old. I attended their spring camp as a trial and I liked it so much, I came back for their summer program. Here, I am helping a kid younger than me practice falling by gently pushing him down to the floor.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Julia Futo is neurodiverse, an intern at Different Brains, a college student, and martial artist whose purpose is helping people find their voices. She enjoys reading, writing, art, music, Zumba, and helping others.