ANCORA IMPARO

RICK RADER, MD ■ EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Quasimodo Syndrome

There is no such thing as Quasimodo syndrome; I made it up. I use it because I am guaranteed that none of my students (medical students, interns, residents, fellows and attendings) have ever heard of it and thus I get their attention – sometimes for as long as 10 minutes.

If you're in the field of developmental medicine (providing healthcare for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities), you spend considerable time navigating the minefields of diseases, disorders, disabilities, impairments, illnesses and syndromes.

While the terms are often used interchangeably, they are in fact not the same. The terms mean different things and those differences often impact on eligibility for services, treatment, reporting, diagnostics, research, inclusion in clinical trials and funding. Over the years I have included explaining the distinctions in my training. It's important for clinicians, educators, researchers, funders, families and patients to appreciate the difference between a specific disease and a syndrome. While there are approximately 30,000 known human diseases, not all of them are syndromic. Most of the readers of EP are familiar with (or at least heard the names) Down syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome, Williams syndrome and Fragile X syndrome. I emphasize the importance of learning about syndromes since they can provide a GPS to better understand, anticipate, and respond to the variety of moving parts found in most syndromes.

I use Quasimodo syndrome as an example of how we need to approach and cogitate about syndromes that we never heard about, read about or thought about. For full disclosure, there is no such thing as Quasimodo syndrome; I made it up. I use it because I am guaranteed that none of my students (medical students, interns, residents, fellows and attendings) have ever heard of it and thus I get their attention – sometimes for as long as 10 minutes. I had to resort to using Quasimodo syndrome since I had to stop using Walking Corpse Syndrome (also known as Cotard's syndrome) which I thought was rare enough that no one would be familiar with. That worked for 11 years until an intern nodded when I mentioned it and shared that his older brother had it. It was then and there that I decided that I would outsmart this new crop of millennials.

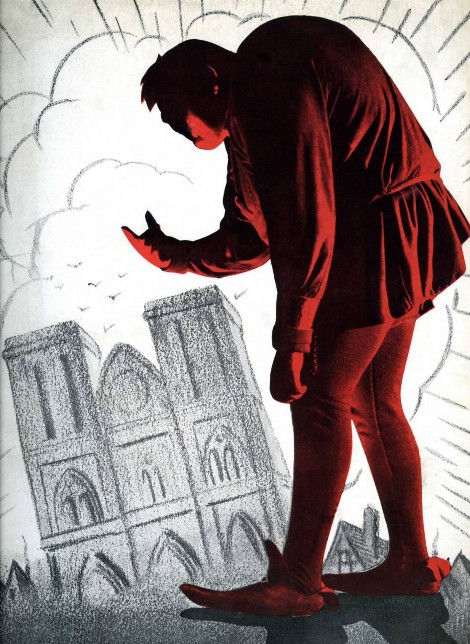

SANCTUARY: Charles Laughton portrayed Quasimodo in the 1939 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Feared by the townspeople as a sort of monster, Quasimodo finds sanctuary in an unlikely love that is fulfilled only in death.

Quasimodo was the fictional character and the main protagonist of the novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo. Douglas Harper shares that "Quasimodo was born with a hunchback and feared by the townspeople as a sort of monster, but he finds sanctuary as a sort of monster, but he finds sanctuary in an unlikely love that is fulfilled only in death." I can remember seeing several movie adaptations of the story starring Lon Chaney (1923), Charles Laughton (1939) and Anthony Quinn (1956). I believe it was among my earliest introductions to human variation, intolerance and the cruelty experienced by these unfortunate individuals.

I was delighted in being the creator of Quasimodo syndrome and wondered about other "made up" diseases. Real diseases have long been part of the storyline in fiction. Boccaccio (circa 1353), in his book The Decameron, tells the story of 10 people of Florence who escape from the Black Death. Tuberculosis was a common disease in the 19th century, and was a major player in Russian literature, including Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment and Kirilov's The Possessed. The Brits saw the significance of TB in the works of Charles Dickens (Dombey and Son), Gaskell's North and South, and Ward's Eleanor. John Dugdale in to fight it." his book Plague Fiction, suggests that "Albert Camus (The Plague) was based on cholera in 19th century France. It was seen as a fable about the need for people to help each other in the meaningless world seen by existentialism, and as alluding to the German invasion of France, fresh in Camus's mind."

Nancy Wexler, writing in the British medical journal The Lancet offers, "Huntington's disease appears in many novels, such as Ian McEwan's 2005 Saturday. It was criticized for its negative portrayal of the protagonist with the disease.

Netflix and other movie channels feature an abundance of movies featuring Zombie apocalypses, fast spreading viral invasions (perhaps too close to home), roaming rabid animals spreading instant death, unstoppable super bugs and alien's proclivity to shrink humans simply by commanding it.

Thanks to Hans syndrome but how can we accelerate its spread, achieve 'herd acceptance' and hope we never foster antibodies Qu for sharing some fictional diseases that we should be glad we don't have to suffer from nightly White House briefings on how to prevent their spread. Carnosaur Virus: This airborne pathogen infects and impregnates women with dinosaur embryos, which Alien their way out of the unwilling mothers' wombs. Ostensibly the goal of this genetically-engineered virus is to wipe out humans and allow dinosaurs to rule the world once more.

MM88 Virus: A super virus that amplifies the negative effects of other viruses and bacterium, making it extremely deadly. The epidemic kills off the entire world population except for 855 people stationed on an Antarctic base. Eventually, everyone dies in a nuclear fire anyway, which is one way to eliminate the virus.

Simian Flu (Planet of the Apes): ALZ-113 is interesting because it demonstrates radical ly different symptoms between apes and humans. While it enhances the intelligence of apes, allowing them to form a human-like civilization in less than a generation, it straight-up kills humans. The mutant strain later "devolves" humans, but the only demonstrable example of this is Nova, the little girl who is still capable of expressing emotion and empathy. Meanwhile, the more humanlike Caesar begins to show a more warlike and vengeful disposition by the end of the series, raising the interesting moral quandary: What really defines intelligence?

Perhaps the idea of fictional syndromes is not such a bad idea. Maybe there is something we could learn from this unexplored model. Perhaps it would not be based on how can we stop the spread of the syndrome but how can we accelerate its spread, achieve "herd acceptance" and hope we never foster antibodies to fight it.

TIPS: Total Inclusion of People Syndrome – People who are exposed to this demonstrate an uncanny behavior to care for and about people who appear different from them.

HELP Syndrome: Helping to Eliminate Learned Prejudice – People exposed to this become opposed to stigmatizing people, isolating them and disregarding them.

isolating them and disregarding them. LEARN Syndrome: Learning to Embrace, Accept and Respect Neuro-diversity – People exposed to this finally open up their hearts, minds and communities to people who think, behave, and express themselves differently.

Of course, we would need a fictional organization to ensure that these syndromes do not exhibit a "flattening" of their spread or worse become eradicated. What about the CDC – Celebrate Diversity in the Community. But why fictional? •

ANCORA IMPARO In his 87th year, the artist Michelangelo (1475 -1564) is believed to have said "Ancora imparo" (I am still learning). Hence, the name for my monthly observations and comments. – Rick Rader, MD, Editor-in-Chief, EP Magazine Director, Morton J. Kent Habilitation Center Orange Grove Center, Chattanooga, TN