Recognizing the urgency of school safety related to students with disabilities, the New Jersey Council on Developmental Disabilities adopted a white paper in 2018 outlining issues and challenges. The paper called for better planning, individualized approaches, staff training, and better coordination with first responders.

BY MERCEDES WITOWSKY

Most schools have comprehensive plans for emergency situations – fires, natural disasters, active shooters, terrorism, and the unplanned release of chemicals. Few have effective plans to address the complex, individualized needs of students with disabilities during emergencies.

Currently, there are no national models addressing the needs of students with disabilities in school-based crisis preparedness. As a result, most schools are not fully prepared to support students with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD).

Many schools rely on an approach that forces students with disabilities to simply wait for help. Advocates agree: "sheltering in place" and waiting for help is not a comprehensive solution. It leaves students in harm's way, and may be dangerous to other students and staff. In addition, door barricades and lockdown plans designed to keep children safe often ignore the needs of students with disabilities, who may have adverse reactions to alarms that overwhelm senses, difficulty processing instructions, or an inability to remain still or quiet.

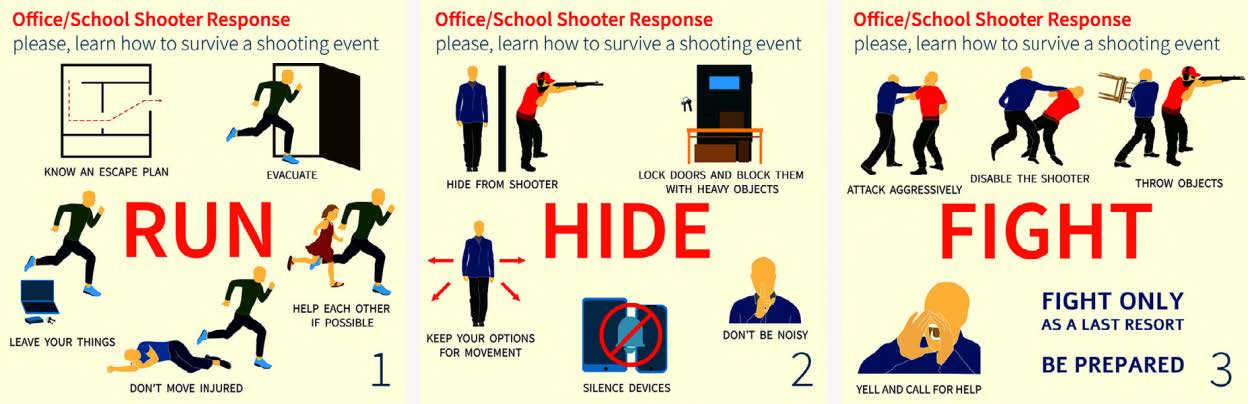

RUN, HIDE, FIGHT

The Department of Homeland Security recommends a "run, hide, fight" strategy during active shootings. This calls for running away from the danger (when possible), hiding somewhere safe when you can't run, and fighting back against a shooter (if running or hiding are not options).

This strategy is not useful for students with disabilities who may not be able to "run." The "hide" aspect of this approach may require students to wait quietly in areas such as libraries, bathrooms, and classrooms until response personnel can assist them – even if these areas aren't accessible or safe. The "fight" strategy may also present challenges for students with mobility, intellectual, communication, and emotional disabilities.

"Run, hide, fight is not close to sufficient planning when considering students with disabilities or special healthcare needs," said Peg Kinsell, policy director, SPAN Parent Advocacy Network, "The absence of school-wide evacuation planning for students with disabilities and special healthcare needs is a gross oversight."

In addition, all students need certain "drill skills" in order to be safe during a school crisis including maintaining silence, following directions quickly, maintaining a position or location, managing feelings of stress/frustration without acting out, and managing schedule changes. Any one of these skills can be problematic—if not impossible—for some students. They must be taught the necessary skills and be provided with accommodations, including sensory, medical, and behavioral supports. For students who are unable to perform these skills, safety rests entirely with staff, who often lack effective training, supports, and time to coordinate response efforts.

"When I was in school my evacuation plan was to wheel myself into the ladies' bathroom, go into the handicapped stall—the only place big enough for my power wheelchair, and turn around with my back to the door," said Kevin Nuñez, vice chair, New Jersey Council on Developmental Disabilities. "I was told that if a shooter came in, the bullets would have to go through the metal door and my wheelchair before they hit me. I was told to wait there, alone, in the dark. That was the plan."

NEW JERSEY'S REQUIREMENTS

In New Jersey, schools are required to have regularly-scheduled drills. They must address all hazards, fire, active shooter, and bomb threats. Since 2011, all New Jersey school districts have been required to have school safety and security plans. These plans are designed locally with the help of law enforcement, emergency management, public health officials, and other key stakeholders. These plans must be reviewed and updated annually. While state guidance on school safety addresses 91 specific planning elements, only one touches on the needs of students with disabilities, requiring schools simply "to accommodate students with disabilities." While such plans must provide for the health, safety, security, and welfare of the school population, very little guidance has been offered in supporting students with disabilities.

DESIGN FLAW: A "run, hide, fight" strategy is not useful for students with disabilities who may not be able to "run." The "hide" aspect of this approach may require students to wait quietly in areas such as libraries, bathrooms, and classrooms until response personnel can assist them — even if these areas aren't accessible or safe.

FEDERAL REQUIREMENTS

Federal law mandates that every child with a disability receive a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment. Children who experience difficulties in school due to physical or psychiatric disorders, emotional or behavioral disabilities, or learning disabilities are entitled to receive special services, modifications, or accommodations at no cost. This includes support for their ability to learn in school and participate in the bene fits of any district program or activity, including emergency preparedness and school safety plans.

- Three federal laws apply to children with disabilities:

- 1) Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 (amended 2008);

- 2) Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1975 (amended 1997); and,

- 3) Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (revised 1978).

The ADA provides "a clear and comprehensive national mandate for the elimination of discrimination against individuals with disabilities." Specifically, the ADA prohibits the exclusion of any qualified individual with a disability, by reason of such disability, from participation in or benefits of educational services, programs, or activities. This includes emergency response in a school safety crisis. IDEA requires schools to provide an individualized educational program (IEP) designed to meet each child's unique needs and provide the child with educational benefit. IDEA requires individual educational success planning for each student on a case-by-case basis through IEP development.

Some students who may be self-sufficient under typical circumstances may have other needs during an emergency. They may require additional assistance during and after an incident in functional areas, including, but not limited to communication, social, sensory, transportation, supervision, medical care, and reestablishing independence. A component of the IEP should consider the child's individualized needs to ensure their safety during an emergency, including evacuation from a classroom and building.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act protects students with a physical or mental impairment substantially limiting one or more major life activities. Often, children covered under Section 504 have impairments that either do not fit within the IDEA eligibility categories or may not be as apparent as those covered under IDEA. The Individualized School Healthcare Plan (ISHP) articulates the healthcare accommodations required for each student qualified for service under Section 504 regulation. The ISHP assists in the safe and accurate delivery of school healthcare services.

Last, Executive Order 13347, Individuals with Disabilities in Emergency Preparedness, was signed by President George W. Bush in 2004. It adds to existing legislative policy ensuring the safety and security of individuals with disabilities are appropriately supported. It also requires public entities to consider the unique needs of individuals with disabilities in their emergency preparedness planning. Clearly, schools have a legal obligation to design plans for the individual needs of students with physical, sensory, intellectual, and other disabilities. Individuals who may lack understanding of a situation, and those who are unable to act quickly must also be accounted for. In addition to students, school personnel and visitors with disabilities also need protection.

School systems must have the capacity to move all students, staff, and visitors with disabilities to a safe location immediately during an emergency. Mitigation (the effort to reduce loss of life and property by lessening the impact of disasters) is a crucial part of emergency planning in schools and should never allow leaving anyone behind because of a disability.

MARYLAND'S EFFORTS

Currently, Maryland is the only state that specifically addresses the needs of students with disabilities in school safety laws. In 2017, Maryland passed legislation ( mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/legislation/details/hb1061?ys=2017rs ) updating guidelines to "accommodate, safeguard, and evacuate" people with disabilities during a school emergency. The law further requires IEPs and 504 plans to address a student's safety needs.

To further improve student safety, Maryland passed the Safe to Learn Act, which solidified school safety plans by mandating assessment teams and the training of school resource officers. To address students with disabilities, officers must receive sensitivity and de-escalation training. In addition, a representative from the state's Protection and Advocacy agency, Disability Rights Maryland, ( disabilityrightsmd.org) was appointed to serve on a committee at the Maryland Center for School Safety. In Maryland schools, students with disabilities are included in emergency plans. Teachers and resource officers must also receive training to ensure student safety.

NEW JERSEY'S CALL TO ACTION

On June 4, 2019, NJCDD convened a Summit on School Safety at the College of New Jersey. Bringing together a diverse group of stakeholders and thought leaders. The NJCDD took a leadership role in creating a forum to discuss issues, challenges, and best practices related to the needs of students with disabilities. The objective was to identify issues while generating tangible solutions to school safety for students with disabilities.

More than 70 guests from the public and private sectors participated in the Summit. Major stakeholders in New Jersey's special education and emergency response communities were represented. Recognizing the urgency of school safety related to students with disabilities, the New Jersey Council on Developmental Disabilities (NJCDD) adopted a white paper in 2018 outlining issues and challenges. The paper called for better planning, individualized approaches, staff training, and better coordination with first responders.

In response, the NJCDD released a comprehensive report, School Safety Issues Affecting Students with Disabilities: A Call to Action. ( njcdd.org/school-safety-issues-affecting-students-with-disabilities) The report includes tangible school safety solutions for students with disabilities. In addition, NJCDD worked with NJ Assemblywoman Mila M. Jasey (D) to introduce a bill (A5828). It requires documentation of students with disabilities' needs during school security drills and emergency situations and in school security plans. It also requires staff training on the needs of students with disabilities in emergency planning. This legislation will ensure that all students can fully participate in schoolwide and building-based emergency response, including full mitigation, practice drills, staff training, and an evaluation process to identify obstacles.

We've only just begun to move the needle on school safety for people with disabilities – we still have much more work to do locally and nationally on this critical issue. •

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Mercedes Witowsky, Executive Director, The New Jersey Council on Developmental Disabilities (NJCDD) was named executive director of the New Jersey Council on Developmental Disabilities (NJCDD) during July of 2018. Witowsky began her career more than 30 years ago as a part-time direct support professional while earning her degree. She is also the proud parent of Anthony and Tina, a young lady with multiple disabilities.