BY DAVID ERVIN

I was recently asked to give a talk to a conference of nurses who specialize in supporting kids and adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (IDD). Easy enough. There's plenty to talk about, that's for certain.

People with IDD continue to experience stubbornly persistent barriers to accessing quality, culturally competent healthcare, and the result is that people with IDD experience high rates of morbidity. Completely preventable and treatable conditions like obesity, hypertension and high cholesterol, diabetes, and mental health concerns like anxiety and depression are found among people with IDD at far greater frequency than among people without IDD. Modern medicine knows how to interact with these conditions; however, our systems of care seem unable or unwilling to do so when it comes to people with IDD.

Developmental Medicine and Dentistry, and the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities are all working on achieving health equity for people with IDD. Superb and innovative models of care are appearing across the country, such as the Lee Specialty Clinic in Kentucky, the Developmental Disabilities Health Center in Colorado, and others are delivering specialty primary care to literally tens of thousands of adults with IDD that is improving health and quality of life. More and more medical schools are formally incorporating elements into their curricula that teach physicians-in-training about people with IDD and their health and healthcare needs.

In late June, Special Olympics International held a one-day summit in Seattle, as part of the 2018 US National Special Olympic Games, which drew thousands of athletes, families, coaches, advocates, health science professionals and others, that focused on health and healthcare. None other than Tim Shriver, the Chairman of Special Olympics International, spoke about the need to contemplate optimal health as a fundamental human right withheld from people with IDD for far too long. So, there was much to talk about with those nurses at that conference. I titled my talk Health Advocacy. •

What are we Buying?

First, I talked about the size of the issue. There are more than 7 million Americans with IDD. Medicaid spending for those 7+ million is between $65 and $70 billion. With a 'B'. Of that, nearly $5 billion – also with a 'B' – is for healthcare. Sounds like a lot of money to me. And since we spend a lot of money, I thought we should talk about the return on that investment. So I did.

I pointed out that men and women with IDD, on average, experience – brace yourselves – between eight and 14 co-occurring health conditions. According to the National Core Indicators, over the seven-year span between 2009 and 2015, an average of 62% of American adults with IDD were overweight or obese. (It's usually at this point that I point out that obesity is not genetically or physiologically inevitable for people with IDD. There are exceptions, of course, as there are for people without IDD, but we have to stop assuming that obesity is the inviolate result of living with an IDD.) People with IDD who experience such unnecessarily high rates of obesity are far more likely to experience unnecessarily high rates of heart disease.

I highlighted extraordinary rates of treatable but largely ignored mental health concerns such as depression. I cited a study that shows that nearly 22% of people with IDD experience some form of mental illness, compared to only 4.3% of people without IDD. And, of course, what do we do with such high rates of mental illness? We medicate. Even as research tells us that polypharmacy – the use of four or more medications or the use of more medications than is medically necessary – is directly related to higher mortality rates, we medicate. A lot.

In 2002, then-US Surgeon General, Dr. David Satcher, published a watershed report called Closing the Gap: A National Blueprint to Improve the Health of Persons with [Intellectual Disability]. (I've taken some editorial liberty by inserting the bracketed words, as I just can't bring myself to using the 'R' word, which was indeed used in the actual title of the report.) In it, Dr. Satcher observed the following:

Compared with other populations, adults, adolescents, and children with [intellectual disability] experience poorer health and more difficulty in finding, getting to, and paying for appropriate health care. Many health care providers and institutional sources of care avoid patients with this condition.

Damning. And unequivocally true. Perhaps more damning still, the report goes on to identify only a smattering of healthcare initiatives across the country dedicated to either primary or specialty care built with and around the needs of people with IDD. We continue to see high levels of treatable chronic disease, poorer health, higher mortality rates, and lower health related quality of life owing to lack of access to culturally competent primary and specialty care long experience by people with IDD. We're spending close to $5 billion on healthcare for people with IDD. What's the return on investment?

Hope. . . and Outcomes

Sixteen years later, there has been progress. More healthcare delivery systems are being built across the US and around the world. From Colorado Springs, CO to Culver City, CA, to Louisville, KY, clinics are being developed to deliver culturally competent, specialty primary care to improve health status and health outcomes experienced by people with IDD.

I happen to work at the Developmental Disabilities Health Center (DDHC) in Colorado Springs, an integrated, primary care clinic that is health home to about 800 patients. Turns out some pretty good things happen when healthcare is designed with and for the unique needs and experiences of people. Patients at DDHC are experiencing improvements in rates of things like depression, hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Risk weight among patients at DDHC is 34% lower than among patients who are not receiving their care at DDHC.

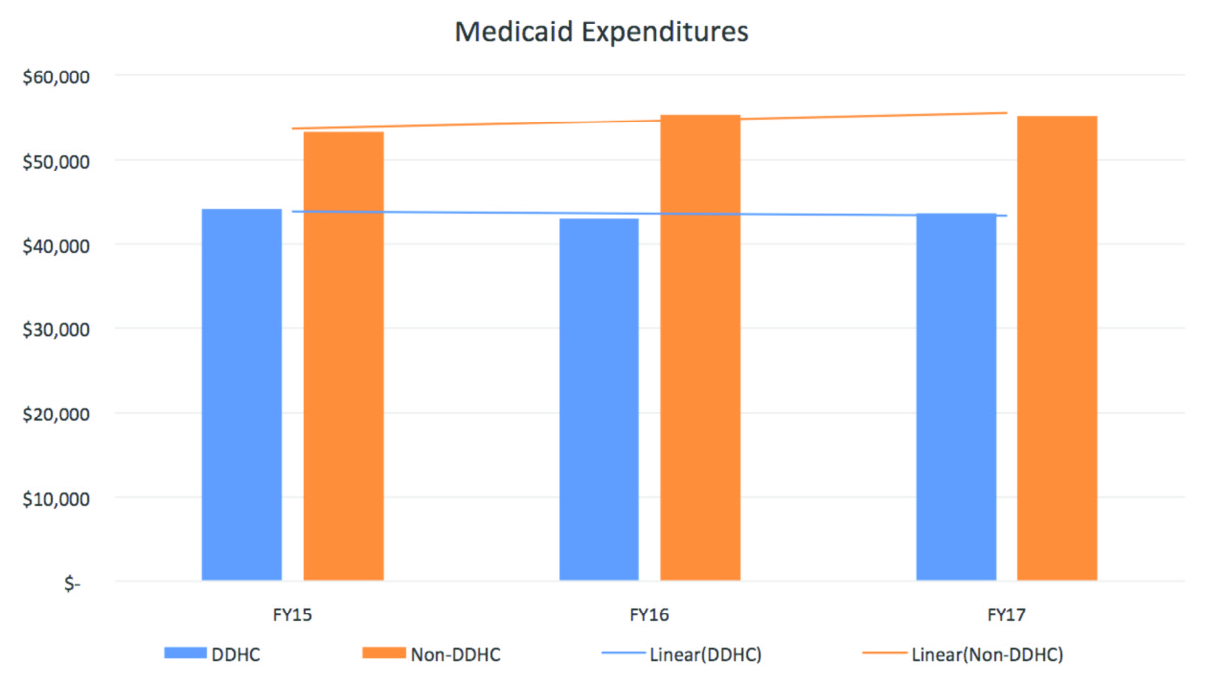

We're also seeing changes in the way people with IDD are accessing healthcare. Emergency department visits among people receiving their healthcare from DDHC are decreasing over time and when compared to people not receiving care at DDHC. Rates of inpatient admissions and of readmissions (for the same or related condition) are more significantly decreased among patients of DDHC. Predictably, when healthcare utilization changes like this, so too do costs associated with that healthcare. In 2017, total Medicaid expenditures among people receiving their healthcare at DDHC is – brace yourselves – 28% lower than among their peers not receiving their healthcare at DDHC. On their own, costs associated with prescription medication are just under 22% lower for people at DDHC! Impressive, right? We can improve health outcomes, make less use of more expensive healthcare resources that do little to improve health status. Now that's return on investment.

But here's the thing we think is the most worth noticing. We ask people if they're happy with their lives. I know, I know. Schmaltzy. But, we think, particularly in the context of a person's health status, that it's logical that people in good health are more likely to be happy with their lives that people in poor health. So, we ask people who receive their healthcare at DDHC if they're happy with their lives. Patients for whom the DDHC is their health home for six months or more report being happy with their lives at a rate that is 29% higher than

patients who are new or newer to DDHC. Lots of things are likely to influence a person's happiness with life, health being but one, but one which we believe worth paying attention.

Health Advocacy

Quality, culturally competent healthcare does, it would seem, produce improvements in health status at a lower cost, and people appear to be living happier lives as a potential result. This is certainly the case in Colorado Springs at DDHC, but there's plenty of reason to believe it's also the case in Culver City and Lexington and anywhere else we choose to dedicate ourselves to addressing health and access to healthcare finally and fully. That's where the Health Advocacy comes in.

Did you know, for example, that following years and years of tireless advocacy, the National Council on Disability, in the Fall of 2017, published its first ever issue brief on the need for quality dental care by people with IDD? The brief, entitled Neglected for Too Long: Dental Care for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, came with a recommendation that "all dental students have more robust training in the care of [patients with] IDD," among a host of others.

Did you know that a small but growing number of US-based medical schools are focusing unprecedented attention on teaching medical students about IDD, common social determinants of health that characterize the life experience of people with IDD, and the chronic conditions that tend to accompany them, and how to appropriately interact with people with IDD? The April 2018 publication of the Core Competencies on Disability for Health Care Education is a gigantic step forward in teaching future physicians and other health science professionals about people with IDD and their health needs.

New primary and specialty care clinics that are developed with people with IDD are opening across the country and around the world. A new project in Montreal, Canada called Voyez les Choses À Ma Façon (See Things My Way), dedicated to delivering culturally competent healthcare to people with IDD, is being developed. A San Antonio, Texas-based Federally Qualified Health Center is exploring the development of a multi-disciplinary primary and specialty care clinic dedicated to the needs and health experiences of people with IDD. And more are coming.

These advances are the result of people with IDD, their families and advocates, healthcare providers, policy wonks and others pushing a policy agenda that demands that people with IDD have access to quality healthcare that delivers superb health outcomes. In that 2002 report, Dr. Satcher outlined six objectives in addressing the need for quality healthcare for of people with IDD. They are as relevant today, 16 years later, as when they were first published. • Integrate Health Promotion into Community Environments of People with IDD • Increase Knowledge and Understanding of Health and IDD, Ensuring that Knowledge Is Made Practical and Easy to Use • Improve the Quality of Health Care for People with IDD • Train Health Care Providers in the Care of Adults and Children with IDD

• Ensure that Health Care Financing Produces Good Health Outcomes for Adults and Children with IDD • Increase Sources of Health Care Services for Adults, Adolescents, and Children with IDD, Ensuring that Health Care is Easily Accessible for Them Much has changed since 2002, and we have come a long way. There remains much work to do.

There remains much work to do. We need financing systems that invest in people with IDD and their health. We need options and opportunities for physicians in medical school and other health science professionals-in-training to learn about people with IDD, and we need to cultivate students' interest in serving this community through designation of people with IDD as a Medically Underserved Population (MUP). We need a set of clinical guidelines, much like exists in Canada in the Primary Care of Adults with Developmental Disabilities: Canadian Consensus Guidelines, which establishes minimum standards of care for people with IDD. We need specialty and subspecialty boards to offer board certification in developmental medicine for adults with IDD – we have Board-recognized subspecialties in developmental and neurodevelopmental Pediatrics that focus on children with IDD, but no corollary for adults. And, we need health promotion and wellness resources that are culturally and linguistically competent and built with and for people with IDD. We surely need other stuff too, I said to those nurses, but this is a pretty good start. As I closed my talk with those nurses, I asked them two questions. If not us, who? And, if not now, when? It must be us. And, it must be now.•

BETTER OUTCOMES: "Turns out some pretty good things happen when healthcare is designed with and for the unique needs and experiences of people."

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: David Ervin is CEO of The Resource Exchange, a Colorado-based nonprofit serving children and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) across the lifespan. He has extensive professional experience in the IDD industry, having worked in and/or consulted to organizations in the US and abroad. He is a published author and speaks internationally on healthcare for people with IDD and other areas of expertise. In 2018, David was conferred Fellow status with the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. He is Associate Editor for the journal Frontiers in Public Health, and a Governor's appointee to and elected Chair of the Colorado State Board of Human Services. He is a Consultant to Exceptional Parent (EP) magazine.