Consider this Eventuality:

HEALTH BEHAVIOR

Question: Will your youngster with a disability 1) smoke, 2) be obese and 3) binge on alcohol when he/she reaches the early and later years of adulthood?

Response: Statistically speaking, compared to 18+ year olds with no disabilities, the answer is probably 1) YES, 2) YES, and 3) maybe NO?

Yes, we know that your youngster with special needs is now 10, 12 or 15 years of age. Given the complexities that must arise as you and your family struggle to raise your child at this age, do you really need to consider the theoretical difficulties that must be faced as he/she reaches the early years of adulthood? Unfortunately, the response is yes!

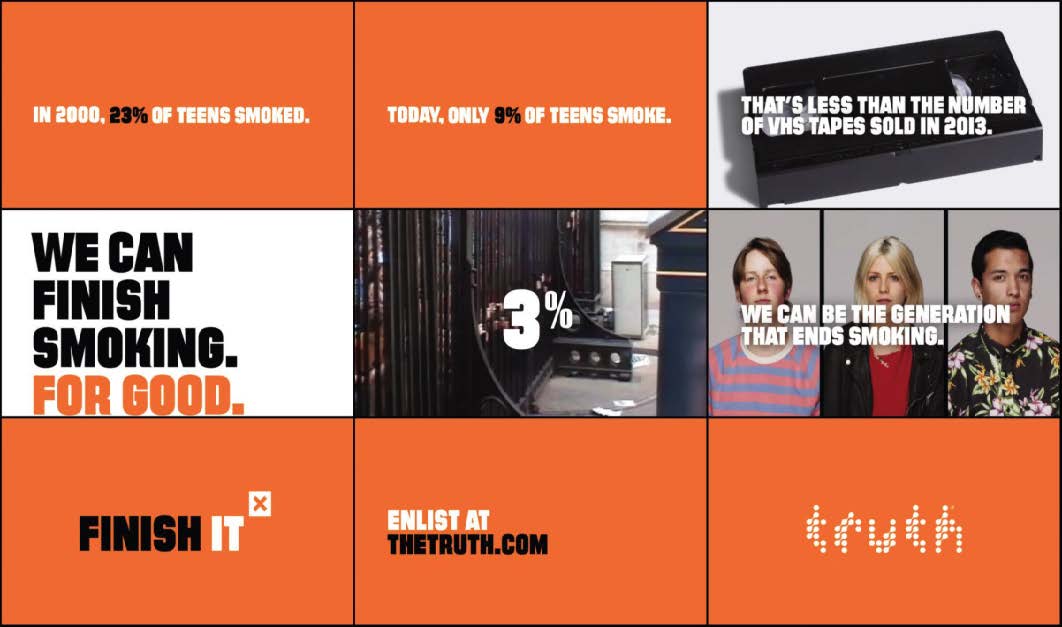

SMOKING

"From the beginning, there was deceit. In January 1954, the CEOs of every major US tobacco company gathered in New York City to plan a coordinated response to the devastating public reaction to a major smoking-and-cancer scare… the findings of a new research indicating smoking as a cause of lung cancer… in Reader's Digest article titled "Cancer by the Carton."… The industry was scared by the plummeting sales as smokers were (alerted) by news about lung cancer." 1 (See Graph 1) "The industry execs responded by publishing a 'Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers'… in more than 400 newspapers in the US, reaching more over 40 million people …asserted that there was no proof that smoking caused lung cancer." 1

When the incidence of smoking decreased in the mid-1950s, the tobacco industry responded by marketing filtered cigarettes, "letting the flavor through" while blocking the substances that caused cancer. Then in 1964, the government issued Smoking and Health, the first Surgeon General's report on the dangers of smoking. With few exceptions, smoking had declined annually in the next 50-plus years; aided by the establishment of tax increases, smoke-free workplace laws, restrictions on advertising, prohibition of sales to minors and litigation against the tobacco industry. "Today, America's smoking market place is dominated by those with less education and lower socio-economics. Notably, a disproportionate number of smokers are people suffering from mental illness and other forms of substance abuse." 1 Nevertheless, consider the attractive reasons for smoking by teenagers and young adults: 1) peer pressure, 2) social reward, 3) risk-taking behavior, 4) parental influence (they may smoke), 5) misinformation, 6) genetic predisposition, 7) advertising, 8) self medication, 9) media influence (movies and television) and 10) stress relief. 2

ISKY BUSINESS: Will your youngster with a disability smoke, be obese and binge on alcohol when he or she reaches the early and later years of adulthood? Statistically speaking, compared to 18+ year olds with no disabilities, the answer is probably yes.

These attracting reasons for smoking may well be intensified as teenagers and young adults with disabilities seek to fit in with "the crowd."

The 2017 Annual Disability Statistics Compendium details nationally and by state an extended range of issues between individuals with disabilities and no disabilities for those who are 18 years and over.3 Specifically, in the United States in 2016, the proportion of individuals 18 years and older with disabilities who smoked (24.8%) was almost double the rate for their counterparts with no disabilities (13.5%).

At the state level, there were wide variations in the proportion of adults who smoked. At the high end, among individuals with disabilities, 34% smoke in Missouri; compared to 21.5% of individuals with no disabilities in West Virginia. At the low end, 15% of individuals with disabilities smoked in Utah and 7.2% of individuals with no disabilities smoked in the same state. (See Table 1)

OBESITY

"In the United States, we don't fear Plague as Europeans did in the 17th century. Instead, we have our own "plague," and its name is obesity. Obesity doesn't kill us as quickly as the Plague, but it does so just as certainly, and is capable of causing much human misery along the way (not to mention the costs to Society in lost productivity and health care costs). And because of the relatively slow onset of its damaging effects, we don't fear obesity like we should… obesity in America is now the second leading preventable cause of death, right there behind our old friend tobacco, and accounts for approximately 300,000400,000 deaths per year." 4 As with smoking, the 2017 Annual Disability Statistics Compendium details the obesity plague at the national and state levels between individuals with disabilities and no disabilities for those who are 18 years and over. 3 Specifically, in the United States in 2016, 38.9% of individuals 18 years and older with disabilities were obese, compared to 25.4% of their counterparts with no disabilities. Regarding the state levels, at the high end, among individuals with disabilities, 43.8% in Alabama and 43.7% in West Virginia were obese, compared to 34.2% of individuals with no disabilities in Mississippi. At the low end, 29.6% of individuals with disabilities were obese in Hawaii and 19% of individuals with no disabilities were obese in the District of Columbia. (See Table 2)

BINGING ON ALCOHOL

Binge drinking is the most common, costly, and deadliest pattern of excessive alcohol use in the United States. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines binge drinking as a pattern of drinking that brings a person's blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08 grams percent or above. This typically happens when men consume 5 or more drinks or women consume 4 or more drinks in a period of about 2 hours. Most people who binge drink are not alcohol dependent. Binge drinking is more common among people with household incomes of $75,000 or more and higher educational levels. Binge drinkers with lower incomes and educational levels, however, consume more binge drinks per year.5 (See Graph 2 for distribution of binge drinkers by age) Binge drinking has serious risks.

• "Unintentional injuries such as car crashes, falls, burns, and alcohol poisoning.

• Violence including homicide, suicide, intimate partner violence, and sexual assault.

• Sexually transmitted diseases.

• Unintended pregnancy and poor pregnancy outcomes, including miscarriage and stillbirth.

• Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

• Sudden infant death syndrome.

• Chronic diseases such as high blood pressure, stroke, heart disease, and liver disease.

ease, and liver disease. • Cancer of the breast, mouth, throat, esophagus, liver, and colon.

• Memory and learning problems. • Alcohol dependence. " 5

• Alcohol dependence. " 5

Contrary to the previous two examples (smoking and obesity), compared to individuals with no disabilities, a smaller proportion of individuals with disabilities who are 18 years and older, reported binging on alcohol.3

Specifically, in the United States in 2016, 13.1% of individuals 18 years and older with disabilities reported binging on alcohol, compared to 18.3% of their counterparts with no disabilities. At the state level, at the high end, among individuals with disabilities 21.6% reported binging alcohol in Wisconsin. In the same state, 25.4% of individuals with no disabilities reported binging alcohol. At the low end, 8.2% of individuals with disabilities reported binging alcohol in West Virginia, compared to 12.9% of individuals with no disabilities in Utah. (See Table 3)

Should parents be complacent that individuals with disabilities reported lower rates of binging on alcohol than their counterparts with no disabilities? Not really! There are 36.2 million individuals, 18 years and over, with severe disabilities. 6 The equivalent of 4.7 million adults with disabilities (13.1%) reported that they had experienced binge drinking.3

Recommended strategies to prevent binge drinking include:

• "Using pricing strategies, including increasing alcohol taxes.

• Limiting the number of retail alcohol outlets that sell alcoholic beverages in a given area.

• Holding alcohol retailers responsible for the harms caused by illegal alcohol sales to minors or intoxicated patrons.

• Restricting access to alcohol by maintaining limits on the days and hours of alcohol retail sales.

• Consistently enforcing laws against underage drinking and alcoholimpaired driving.

• Maintaining government controls on alcohol sales (avoiding privatization).

• Screening and counseling for alcohol misuse." 5

ONCE AGAIN

Do you need to consider the unforeseen difficulties that must be faced as your youngster with special needs reaches the early years of adulthood? Most advice for these complications often concentrates on economics, living arrangements and supervisory issues. But what of the issues of "life style?" Smoking, obesity and alcohol consumption are three issues that seem both far away and a low priority in the early formative years. But just as we seek to establish a wide range of patterns of life for our youngsters in their early years, so too must we consider their "living style." Have you considered these issues in your planning for the adult future of your child with special needs?

Director, Advanced Specialty Education in Pediatric Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics & Pediatric Dentistry, Stony Brook University, NY. Nevin Zablotsky, DMD is s Senior Consultant and Lecturer on Tobacco Curriculum Nova Southeastern University College of Dental Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, FL. Steven P. Perlman, DDS, MScD, DHL (Hon) is Global Clinical Director, Special Olympics, Special Smiles and Clinical Professor of Pediatric Dentistry, The Boston University Goldman School of Dental Medicine.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS: H. Barry Waldman, DDS, MPH, PhD - Distinguished Teaching Professor, Department of General Dentistry at Stony Brook University, NY; E-mail: h.waldman@stonybrook.edu Andrew G. Schwartz, DDS, FACD is Clinical Assistant Professor Director, Division of Behavioral Sciences and Practice Management, Department of General Dentistry School of Dental Medicine, Stony Brook University, NY. Charles D. Larsen, DMD, MS, is Assistant Professor