"The SNAP Program makes a vital contribution to the armamentarium of best practices addressing the unique needs of special populations and their ability to thrive and participate in the community. It will become a time-honored component in the first responders' toolkit." – Rick Rader, MD, Medical Liaison, SNAP Program

Even under the best of circumstances, it is challenging to be a good parent, but when your child has special needs, it gets even harder. These caregivers must attend to those challenges every day. To cope, they read articles, books, and attend training classes when they can. They also learn from other caregivers. In fact, many will tell you that they often learn more from each other about day-to-day living with a diagnosis than they can get from professional medical personnel.

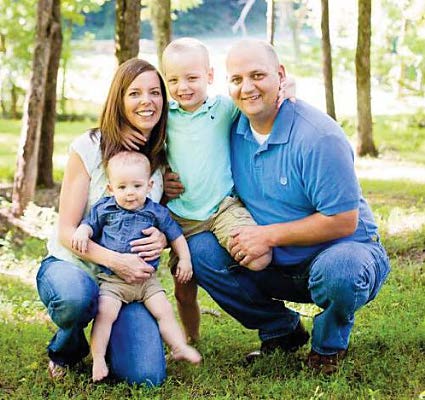

People with special needs may have physical, developmental or intellectual disabilities, such as autism, Down syndrome, epilepsy or a wide variety of mental illnesses. According to Cornell University's Disability Status Report for 2015, roughly 40 million of the 317 million residents in the US reported having one or more disabilities. Captain Skyler Phillips with the Chattanooga Fire Department has a lot of experience with caring for someone who has special needs. His six-year-old son Noah has autism. Together with his wife Melissa, they have learned a great deal about how to recognize and care for someone who has autism. They also have a two-year-old son, Elliott. Sure, they love both kids dearly, but when Noah "has a meltdown," it can be a trying experience. Just recently, with help from extended family, friends and the Chattanooga Fire Fighters Association, Local 820, the family acquired a service dog, which has helped Noah tremendously in navigating life with autism. Like Noah, there are many people across the country with autism or any number of other special needs. So what happens when first responders encounter them on an emergency scene? Phillips has been through extensive training, but there are gaps. "I've been through a lot of training: EMT, paramedic, six months in the fire academy, thousands of hours with Urban Search and Rescue and hazardous materials," said Phillips. "I've had all of this training over my 14 years with the department, but not one class related to special needs."

That gap in training for special needs is now closing. Phillips teamed up with Lisa Mattheiss, founder of LifeLine, Inc., a nonprofit organization based in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and created a four-hour training class called the Special Needs Awareness Program, or SNAP. They developed the curriculum for this training with input from current and former police officers, military and civilian emergency medical personnel, and parents. The class addresses more than 30 different diagnoses, or special needs, within the SNAP curriculum. Captain Phillips taught the class for the first time in the Chattanooga Fire Department's annual in-service training program earlier this year, and he also has taught the class for several nearby agencies. SNAP is comprised of two parts. Phillips will be handling the First Responder Training, and Mattheiss will be handling the Family Emergency Preparedness Training.

SNAP provides instruction that other training programs do not cover. "This program teaches first responders how to assess the people they encounter," said Phillips. "When you arrive on a scene and you see someone who may look or behave differently from what you expect, you will be better equipped to recognize if that person has a developmental or intellectual disability." The idea is to equip first responders so that they can identify people with special needs, to interact with them in a way that calms the situation and prevents escalation. When someone is being difficult or not appearing to comply, first responders need to think about why they are acting that way. "People with special needs are not necessarily trying to be difficult," said Phillips. "They may do some things that may look different or appear to be unusual to us, but it's not always a sign of non-compliance or aggression."

On emergency scenes, such as house fires or car wrecks, people with special needs may be experiencing what experts call "sensory overload." It can be chaotic on emergency scenes, with first responders showing up in uniforms, wearing masks and gloves. Then there's the noise, with sirens and people talking loudly, or even shouting. All of these can trigger certain behaviors, such as the urge to run, fight, withdraw or even get sick and throw up. It's up to the first responders to recognize what's going on with someone who has special needs.

First responders need to look for visual and verbal cues to identify someone with special needs, and then act accordingly. "For example, when you interact with someone, look for echolalia, where they repeat what you say," said Phillips. "If you see things like that, then you know that this might not be your typical call and you might have to think outside the box."

Phillips cited his own son as an example. "Noah does not have fine motor control," said Phillips, "so he wears pants and shoes with Velcro. Those are things you can look for." Phillips trains responders to observe the way certain people with disabilities speak, which will help first responders spot the difference between someone who is drunk, or high, from someone who has a disability. Before a first responder assumes an individual is non-compliant, they are encouraged to consider if there could be other factors at play. SNAP training is designed to help first responders filter what they are seeing, based on what they have learned from caregivers and those affected by disability.

Surprisingly, people with disabilities may not want to call 911 for help, even if they need it. "Their lives look different from other people," said Phillips, "so they may not be comfortable calling strangers to their home." In a home that has someone with special needs, you may see door knobs turned around backwards, locks on refrigerators, and even bars on windows. "These people may not want to explain it to you for fear of someone calling child protective services," said Phillips. "There are a lot of things they have to do in their lives to protect their children that first responders may not understand."

Mattheiss agrees, saying that many special needs families have kids who are "runners." "They may just walk out of the house and disappear without telling anyone," said Mattheiss. "Parents may place multiple locks on their doors to keep that from happening." For these families, there is concern and anxiety that first responders may not understand what's going on. Obviously, using locks to prevent "runners" presents its own unique challenges. Mattheiss says an emergency plan needs to be in place to react quickly. In the event of a fire, for example, everyone needs to know how to unlock the doors and get everyone out together as quickly as possible, to an agreed upon meeting place.

Mattheiss will be handling the Family Emergency Preparedness Training part of SNAP. "This training will include emergency preparedness for major community crisis or catastrophic events as well as preparation for personal emergencies that may occur at home, in a car, or in the community," said Mattheiss. "Parents and caregivers will be equipped with information about how they can prepare to promote safety for themselves, the ones they care for, and the first responders in a crisis situation where emergency personnel are called to their home, car wreck, car breakdown, or medical emergency."

MEETING OF THE MINDS: Captain Phillips (standing, center) teamed up with Lisa Mattheiss of LifeLine, Inc., a nonprofit organization based in Chattanooga, and created a four-hour training class called the Special Needs Awareness Program, or SNAP.

Like Captain Phillips, Mattheiss can speak firsthand about special needs. She and her husband Jeff are the parents of a child with special needs. Emily Christene Mattheiss was born with spina bifida and hydrocephalus and has now accumulated almost 30 diagnoses altogether. Eighteen years and 16 surgical procedures later, Emily has multiple disabilities including mobility impairments, multiple medical diagnoses, developmental disabilities, and learning disabilities.

For six years, Mattheiss served on the National Council on Disabilities and traveled all over the country, learning a lot about how people deal with disabilities. She traveled with a team to New Orleans two years after it was devastated by Hurricane Katrina, and listened to testimony from families with disabilities and first responders. "That was one of the most emotionally draining, gut-wrenching three days I've ever experienced," said Mattheiss. Why was it so bad in New Orleans? Mattheiss attributed many of the problems to a lack of planning and resources. "The local government was not ready and the residents were not prepared," said Mattheiss.

Why was it so bad in New Orleans? Mattheiss attributed many of the problems to a lack of planning and resources. "The local government was not ready and the residents were not prepared," said Mattheiss. "People who couldn't evacuate themselves were stranded. Normal communication was knocked out. It was just horrible," said Mattheiss. "You just wouldn't think that kind of bad stuff would happen in this day and age, but it did."

She was heartbroken to see first responders who did not know how to handle people with special needs, perhaps in part because they couldn't even identify people with special needs. "Some residents refused to leave their homes," said Mattheiss, "not because they were trying to be difficult, but because they were afraid to leave the one place they felt safe." When some of the people with disabilities were evacuated, the first responders would not allow them to bring their equipment. That's understandable when the first responders were using small boats and didn't have room, but they wouldn't allow

smaller things like walking canes and other smaller pieces of equipment that made the difference between dependence and independence for that person when they got to their destination. Even two years later, there were people who were triying to get by with out the equipement they lost in the hurricane. In many cases, they simply couldn't afford to replace what they lost.

HOLDING OUT: "Sometimes we hesitate to call 911 because we don't know how the first responders will react then they arrive. "The Mattheiss family, (From left to right), Lisa, Emily, Caroline and Jeff.

Mishandling people with special needs doesn't have to involve a widespread disaster. It can turn tragic with a one-on-one encounter. Mattheiss cited an incident that occurred last year involving a young man in his early 20s with developmental disabilities who had an aide with him. They were out in the community and the young man started having a meltdown. Mattheiss said the police were called in and, rather than work with the aide who knew him very well, the police officer shot him because he considered the young man a threat. "The aide pleaded with the officer to allow him to work with the young man," said Mattheiss, "but rather than work with the aide, the officer shot him." This happens more often than most people realize. "This is the fear that our families have," said Mattheiss. "Many of our kids have severe and extreme behaviors. They can be fine some of the time, and then suddenly, they are not. So, sometimes we hesitate to call 911 because we don't know how the first responders will react then they arrive."

The situation can be even worse on emergency scenes, where conditions are far from normal. "We want to prepare not just the first responders, but the families as well," said Mattheiss, "so that when they come together on emergency scenes, all parties are trained and know how to handle the situation better. It could mean the difference between life and death."

With or without the added challenge of special needs, Mattheiss says everyone should plan for an emergency. "I have a list of all my documentation about my daughter, and I sent a copy of that list to my parents in Ohio," said Mattheiss. "It's just an email that I send so that if my laptop dies or my house burns with my hard copies, I have a backup somewhere else." These are simple, little things that can make a huge difference. If you wait for the emergency, you may not be able to tell someone the exact medications you or a loved one takes, from memory, especially if you have special needs and you're alone. "We all think it's not going to happen to us, and then it happens." Lisa's class will help families prepare for emergencies. That could include contacting your doctor and asking for an additional five more pills to go in that emergency kit. Once you compile all the important medical information, you keep it in a safe place for yourself, and then send a copy to a relative or close friend elsewhere in the state, or out of state. If something catastrophic destroyed your home, you would still have that information somewhere else.

With help from Dr. Rick Rader, director of rehabilitation at Orange Grove Center, SNAP was adopted state-wide earlier this year by the Tennessee Fire Commission. The Orange Grove Center is a private, non-profit organization that serves adults and children with intellectual disabilities. Tennessee is believed to be the first state in the country to mandate SNAP training for every firefighter.

The Chattanooga Fire Fighters Association, Local 820, is paying for the creation of "sensory kits" that will be placed on all the apparatus in the department. It will have things like Legos, balls, coloring books, crayons, Play-Doh and stickers; things that are sensory friendly for children who are seeking sensory input. "If their home was on fire and all their stuff burned up, they're not going to have that stuff with them," said Phillips. "So, our firefighters will be able to pull this kit out give the child something that will make them feel better." The firefighters will also get manuals on their fire apparatus that will have quick reference summaries of how to interact with people with specific disabilities. These manuals were developed by the Center for Development and Disability at University of New Mexico. LifeLine will also the be distributing stickers that have the letters "SNAP" on them. They can be placed on cars and homes to let first responders know that someone inside has special needs. their fire apparatus that will have quick reference summaries of how to interact with people with specific disabilities. These Finally, LifeLine will also be distributing "bio forms" that can be kept in their car's glove compartment. These bio forms may also be submitted in advance to 911 dispatch centers in some areas that have the database capacity to enable it. First respon ders can receive this information while responding to the scene, which will better prepare them to interact effectively with those they will be serving.

ASSESS FOR SUCCESS: "SNAP teaches first responders how to assess the people they encounter." The Phillips family, (From left to right) Two-year-old Noah, Mellissa, Elliott and Captain Phillips.

Mattheiss is scheduled to begin teaching her part of the SNAP class to families in September. She will also continue her work with LifeLine, Inc. Mattheiss says LifeLine is an organization that serves families with all types of disabilities. "One of the challenges families face when their child receives a diagnosis is the feeling of being alone," said Mattheiss. "LifeLine has a parent mentor program called ParentLink. It's not just for biological parents, but anyone who gives care to someone with special needs or disability." LifeLine also provides training and support for parents, educators, and professionals on navigating the special education system and resources and referrals within community service delivery systems. Special Needs Ministry development within local churches is a growing component of LifeLine's work as well. SNAP is the most recent addition to LifeLine's services. Lifeline is a 501(c)(3) non-profit, volunteer-driven organization. Donations are tax deductible.