Congress recently put about $12.7 billion toward enhancing state Medicaid programs for home- and community-based services for people with disabilities, but that money will be available only through March 2025. The Build Back Better Act, which died in Congress, would have added $150 billion, and funding was left out of the Inflation Reduction Act, which became law this summer, to the disappointment of advocates.

Jeneva Stone's family in Bethesda, Maryland, has been "flummoxed" by the long-term planning process for her 25-year-old son, Rob. He needs complex care because he has dystonia 16, a rare muscle condition that makes moving nearly impossible for him.

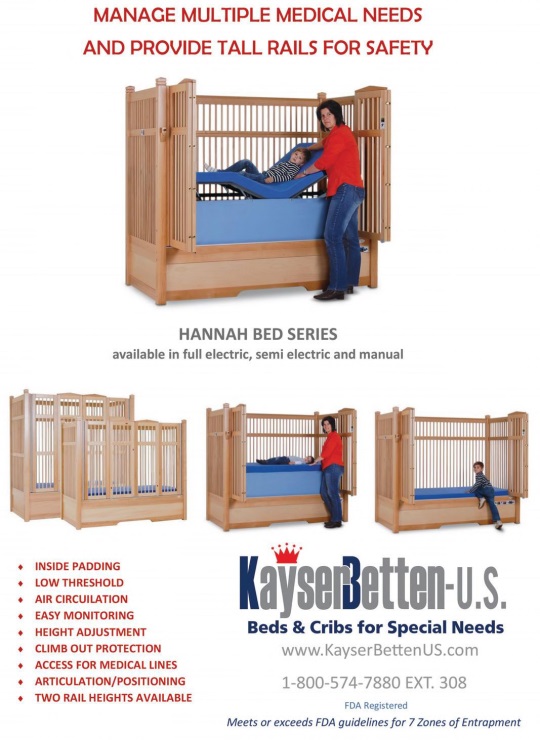

NARROW OPTIONS: Rob Stone was born with a condition that restricts much of his movement. His mother, Jeneva, says her family has been "flummoxed" by the process of planning for the future.

"No one will just sit down and tell me what is going to happen to my son," she said. "You know, what are his options, really?"

Stone said her family has done some planning, including setting up a special needs trust to help manage Rob's assets and an ABLE account, a type of savings account for people with disabilities. They're also working to give Rob's brother medical and financial power of attorney and to create a supported decision-making arrangement for Rob to make sure he has the final say in his care.

"We're trying to put that scaffolding in place, primarily to protect Rob's ability to make his own decisions," she said.

Alison Barkoff is acting administrator for the Administration for Community Living, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Her agency recently released what she called a "first ever" national plan, with hundreds of actions the public and private sectors can take to support family caregivers.

"If we don't really think and plan, I'm concerned that we could have people ending up in institutions and other types of segregated settings that could and should be able to be supported in the community," said Barkoff, who noted that those outcomes could violate the civil rights of people with disabilities.

She said her agency is working to address the shortages in the direct care workforce and in the supply of affordable, accessible housing for people with disabilities, as well as the lack of disability-focused training among medical professionals.

But ending up in a nursing home or other institution might not be the worst outcome for some people, said Berns, who pointed out that people with disabilities are overrepresented in jails and prisons.

Berns' organization, the Arc of the United States, offers a planning guide and has compiled a directory of local advocates,

lawyers, and support organizations to help families. Berns said that making sure people with disabilities have access to services – and the means to pay for them – is only one part of a good plan.

"It's about social connections," Berns said. "It's about employment. It's about where you live. It's about your health care and making decisions in your life."

Philip Woody feels as though he has prepared pretty well for his son's future. Evan, 23, lives with his parents in Dunwoody, Georgia, and needs round-the-clock support after a fall as an infant resulted in a significant brain injury. His parents provide much of his care. Woody said his family has been saving for years to provide for his son's future, and Evan recently got off a Medicaid waitlist and is getting support to attend a day program for adults with disabilities. He also has an older sister in Tennessee who wants to be involved in his care.

But two big questions are plaguing Woody: Where will Evan live when he can no longer live at home? And will that setting be one where he can thrive?

"As a parent, you will take care of your child as well as you can for as long as you can," Woody said. "But then nobody after you pass away will love them or care for them the way that you did."•

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sam Whitehead covers the South for KHN from his base just outside Atlanta. He previously worked as a health care reporter for WABE, where he chronicled the covid-19 pandemic as host of the award-winning podcast “Did You Wash Your Hands?” Before that, he was a general assignment reporter and fill-in radio host at Georgia Public Broadcasting. He co-founded a long-running nightly news program on WRFI Community Radio in Ithaca, New York. He’s a graduate of Emory University.