COVID AND MENTAL HEALTH:

CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS MOST IMPACTED

BY LAUREN AGORATUS, M.A.

Students with disabilities had the most learning loss during the pandemic. Some children with special needs also developed mental health issues.

SO HOW BAD IS IT?

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has declared a national pediatric mental health emergency. The AAP notes that "Children and families across our country have experienced enormous adversity and disruption. The inequities that result from structural racism have contributed to disproportionate impacts on children from communities of color."

The Surgeon General also issued an advisory on the same issue. This report stated that "the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically altered young peoples' experiences at home, at school, and in the community. The pandemic era's unfathomable number of deaths, pervasive sense of fear, economic instability, and forced physical distancing from loved ones, friends, and communities have exacerbated the unprecedented stresses young people already faced."

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES?

Data shows that children with disabilities were impacted the most from challenges due to COVID.1 It is also important to note that there is often comorbidity with mental illness.2 Besides learning loss, students with disabilities also may not have received necessary related services such as: physical, occupational, and speech therapies, resulting in skills loss. Like all children, children with special healthcare needs may have developed mental health issues. Some students who never had mental health issues do now; others who had mental health challenges have seen those challenges exacerbated. Many children with developmental disabilities have regressed and demonstrate more challenging behaviors.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

There has been a movement to integrate behavioral health into primary care. Pediatricians and family providers can do quick

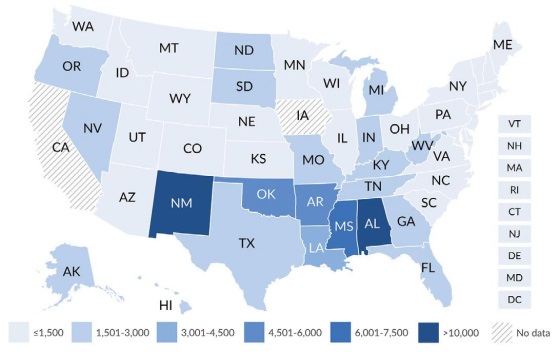

screenings and then refer if needed. However, there are sometimes long wait lists for pediatric mental health providers. In some states, behavioral health integration uses a PCP (primary care provider) in a consultative telehealth model with a mental health provider (see Project LAUNCH grantee states healthysafechildren.org/project-launch-grantees).

Another successful approach is addressing mental health in schools. Since students spend so much time in school, providing mental health services where they are, makes sense. Some states, like NJ, have developed mental health guides with resources and effective practices. Schools can also do mental health screenings and give families referral resources. In addition, schools can help eliminate stigma associated with mental illness and raise awareness. Positive school climate which includes: bullying prevention programs or Schoolwide Positive Behavior Supports, can help. The Center for Parent Information and Resources lists mental health organizations, finding help, and information on specific disorders. The National Federation of Families (for Children's Mental Health) also has information on useful resources. Programs such as: NAMI's (National Alliance on Mental Illness) In

A SHORTAGE OF SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGISTS: The National Association of School Psychologists recommends one professional for every 500 students. Maine is the only state that meets that standard. The current U.S. average of students per school psychologist is 1,211 to one. 3