Ideally, children should have their feet on the floor or support and sit up without slouching (within the constructs of their physical abilities).

As children become comfortable sitting together, gradually introduce the concept of eating at the table. Try to stick to set times for eating as much as possible. Aim for three meals and one snack per day, with no more than 2-4 hours between meals depending on your child's age (note: determine the ideal number of meals/snacks per day with your dietitian). If a child experiences hunger between meals, this provides a learning experience to tune into their bodies. By establishing set times for eating, children can learn to accept food at the appropriate times, and they will come to anticipate their daily routines.

Be a role model! Meals are a powerful time to model ideal behaviors. So, parents, eat a varied diet and demonstrate how you would like your child to behave.

ADDRESSING FOOD SELECTIVITY

Children's food selectivity comes from a place of fear. It is essential to recognize that new foods are very anxiety-provoking and a source of discomfort for many children with ASD.

Gradual exposure may help improve acceptance of new foods and ultimately improve nutritional intake. If a child is fearful of oranges, start by having the child look at an orange from across the room. Over time, move the orange closer and have them touch and play with it. As their comfort increases, show them an orange in different ways; cut into chunks, slices, and orange juice.

juice. Try food-chaining! Food-chaining is an approach where you introduce new foods to your child while building on previously

accepted and successful foods. Dietitian Jenny Friedman, RD, has developed helpful visuals if you need ideas transitioning to new foods. (check her out at jennyfried- mannutrition.com).17

Expand on already accepted foods. If your child accepts McDonald's french fries, try substituting oven-baked fries, then work towards transitioning to zucchini fries. You can also try swapping foods with similar textures (e.g., swap yogurt for pudding).

Focus on the food not the behavior. — Jenny Freidman

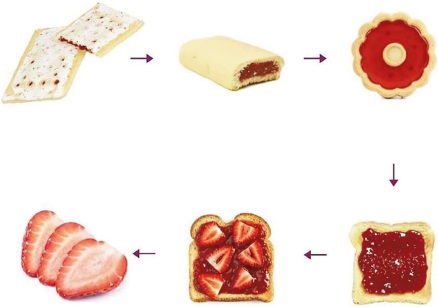

POPTART TO STRAWBERRIES: LEARNING TO ENJOY FRUIT

Food chaining is a way to get your selective eater to try new foods. It takes into account the sensory properties of foods that your child likes and builds on his/her preferences. Essentially, it's a tool that helps you identify which new foods your child is most likely to eat. The chain is created by making gradual changes to the accepted food.

MEALTIME MATTERS : A RECAP

Enlist Support: Find a dietician: eatingright.org/find-a-nutrition-expert Meal Environment: Ease into meals with an anxiey lowering activity • Sit at the same table, consider assigning seats • Establish set meal times • Model ideal behavior. Food Selectivity: Understand fear of new foods is similar to fear of spiders or heights • Try exposure therapy • Consider food chaining to move children away from less nutritionally desirable foods.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Heather Seid, MS, RDN, CPS, CNSC, CLC, is a registered dietitian specializing in pediatric and maternal health, and she is a 2021-2022 Fellow in the New Jersey Leadership Excellence in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities program. She oversees the Bionutrition research core at Columbia University and is a Doctor of Clinical Nutrition student at Rutgers School of Health Professions. Dr. Jane Ziegler, DCN, RDN, LDN is Interim Chair, Associate Professor and Director of the Doctor of Clinical Nutrition Program in the Department of Clinical and Preventive Nutrition Sciences at Rutgers School of Health Professions. She is a faculty mentor in the New Jersey Leadership Excellence in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities program.

References

- Verhage CL, Gillebaart M, van der Veek SMC, Vereijken C. The relation between family meals and health of infants and toddlers: A review. Appetite. Aug 1 2018;127:97-109. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2018.04.010

- Hammons AJ, Fiese BH. Is frequency of shared family meals related to the nutritional health of children and adolescents? Pediatrics. Jun 2011;127(6):e1565-74. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1440

- Association AP. The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. 2013.

- Ledford JG, D. . Feeding problems in children with autism spectrum disorders: a review. . Focus on autism and other developmental disabilities 2006;21:16-27.

- Chistol LT, Bandini LG, Must A, Phillips S, Cermak SA, Curtin C. Sensory Sensitivity and Food Selectivity in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. Feb 2018;48(2):583-591. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3340-9

- Curtin C, Jojic M, Bandini LG. Obesity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. Mar-Apr 2014;22(2):93-103. doi:10.1097/hrp.0000000000000031

- Gray HL, Sinha S, Buro AW, et al. Early History, Mealtime Environment, and Parental Views on Mealtime and Eating Behaviors among Children with ASD in Florida. Nutrients. Dec 2 2018;10(12)doi:10.3390/nu10121867

- Sharp WG, Berry RC, McCracken C, et al. Feeding problems and nutrient intake in children with autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis and comprehensive review of the literature. J Autism Dev Disord. Sep 2013;43(9):2159-73. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1771-5

- Evans EW, Must A, Anderson SE, et al. Dietary Patterns and Body Mass Index in Children with Autism and Typically Developing Children. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2012;6(1):399-405. doi:

- 1016/j.rasd.2011.06.014 ILLUSTRATION COURTESY JENNYFRIEDMANNUTRITION.COM 10. Hill AP, Zuckerman KE, Fombonne E. Obesity and Autism. Pediatrics. Dec 2015;136(6):1051-61. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-1437

- Austin GL, Ogden LG, Hill JO. Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and protein intakes and association with energy intake in normal-weight, overweight, and obese individuals: 1971-2006. Am J Clin Nutr. Apr 2011;93(4):836-43. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.000141

- Tyler CV, Schramm SC, Karafa M, Tang AS, Jain AK. Chronic disease risks in young adults with autism spectrum disorder: forewarned is forearmed. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. Sep 2011;116(5):371-80. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-116.5.371

- Zheng Z, Zhang L, Li S, et al. Association among obesity, overweight and autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. Sep 15 2017;7(1):11697. doi:10.1038/s41598-01712003-4

- Ausderau KK, St John B, Kwaterski KN, Nieuwenhuis B, Bradley E. Parents' Strategies to Support Mealtime Participation of Their Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Am J Occup Ther. Jan/Feb 2019;73(1):7301205070p1-7301205070p10. doi:10.5014/ajot.2019.024612

- DeGrace BW. The everyday occupation of families with children with autism. Am J Occup Ther. Sep-Oct 2004;58(5):543-50. doi:10.5014/ajot.58.5.543

- Jenny L. Clark OL. 3 Deep relaxed breathing exercise to help children with sensory processing disorder and autism. . Accessed January 8, 2022, 2022. jennylclark.com/3-deep-relaxed-breath- ing-exercises-to-help-children-with-sensory-processing-disorder-and-autism/

- Friedman J. Jenny Friedman Nutrition- Guide to Food Chaining. Accessed January 10, 2022, 2022. jennyfriedmannutrition.com/food-chaining-for-autism-picky-eating