ANCORA IMPARO

RICK RADER, MD ■ EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

It Was a Dark and Stormy Night

Exceptional Parent Magazine has evolved. What was once exclusively dedicated to parents is now universally read by all the stakeholders in the disability community.

"It was a dark and stormy night."

That phrase was frequently used by cartoonist Charles M. Schulz in the popular comic strip Peanuts. Ever since I first read it, I wanted to open an article with it. Schulz often depicted Snoopy as an aspiring author sitting on top of his dog house, typing out: "It was a dark and stormy night." Now that I have done that, I guess it's another check off my bucket list.

In actuality, the phrase predated Peanuts. It stands as the universal cry for bad writing and it comes from the first phrase of the opening sentence of English novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton's 1830 novel Paul Clifford. In its entirety, "It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents – except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness."

THE WORLD FAMOUS AUTHOR: In one strip, Linus says Snoopy's stories all begin the same way, and tells the beagle he should change that. Snoopy responds by writing, "It was a stormy and dark night."

Writer's Digest described the sentence as "the literary posterchild for bad story starters." On the other hand, the American Book Review ranked it as No. 22 on its "Best first lines from novels" list. So much for universal agreement on anything.

"It was a dark and stormy night" describes most nights, and most days for parents of children with special health care needs at the dawn of the disability rights movement.

In the early 1970's, the landscape for children with disabilities (adults with disabilities were invisible and off anyone's radar) and their families was bleak, uninviting, and inhospitable. While there were pioneering advocacy efforts prior to that, most families opted to send their children to institutions or keep them isolated at home. Credit has to be given to those progressive organizations that were formed to give a voice to those desperate families. United Cerebral Palsy in 1949, The Arc in 1950, The National Association for Down Syndrome in 1960, and Special Olympics in 1968 were beacons of hope and models for families that had hoped for opportunities for their children to be respected, welcomed, and included in the community.

But, the reality was in the early 1970's, the rights of people with disabilities were not actively promoted or protected by the Federal government. It wasn't until 1973 that the landmark Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act was enacted. The Americans with Disabilities Act did not become law until 1990, and the Olmstead Act was not passed until 1999. Rosa's Law, which addressed the need for appropriate descriptive language, did not appear until 2009.

Part of the reason for the "dark and stormy nights" experienced by families in the early 1970's was the lack of resources for information, places to go for answers to their questions, a network to learn from others and a trusted and supportive "mother ship."

That changed in 1971. It was certainly a dynamic year on all accounts. The year had three partial solar eclipses and two total lunar eclipses. It was the year they banned cigarette advertising on radio and television. Apollo 14 landed on the moon. Rolls Royce went bankrupt. Satchel Paige became the first Negro League player to be voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame from the Negro League. The United Kingdom switched to decimal currency. Evel Knievel set a world record and jumped over 19 cars on a motorcycle. The Ed Sullivan Show aired its final episode. Starbucks, the mega coffeehouse power, was founded. President Nixon declared the U.S. War on Drugs. Federal Express was a start-up company. The hit movie, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, hit the theatres. Two new magazines were started: Ms. Magazine and Playgirl. The voting age was lowered from 21 to 18. Walt Disney World opened in Orlando, Florida. The U.S. dollar was devalued for the second time in history. Hundreds of thousands of Americans protested the war in Viet Nam. The start of the digital age took place with the invention of the microprocessor… And three Boston psychologists saw an opportunity.

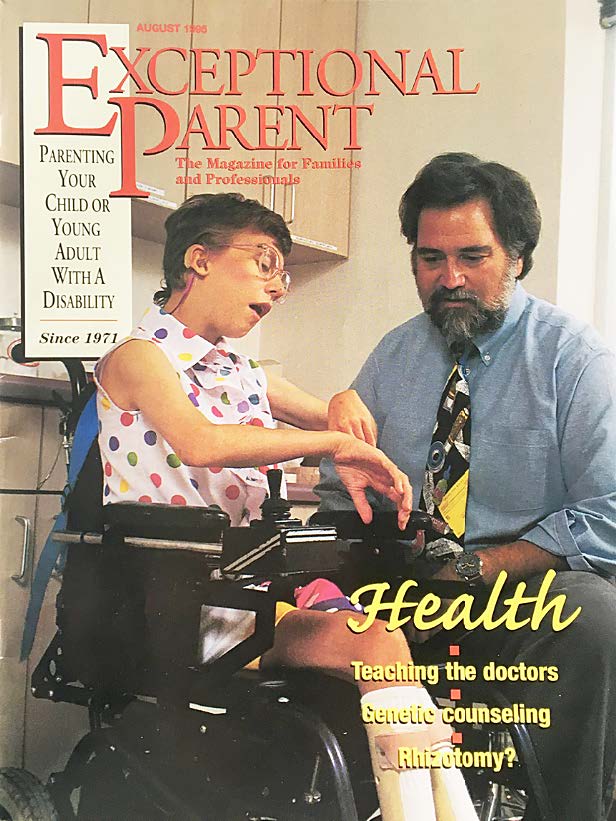

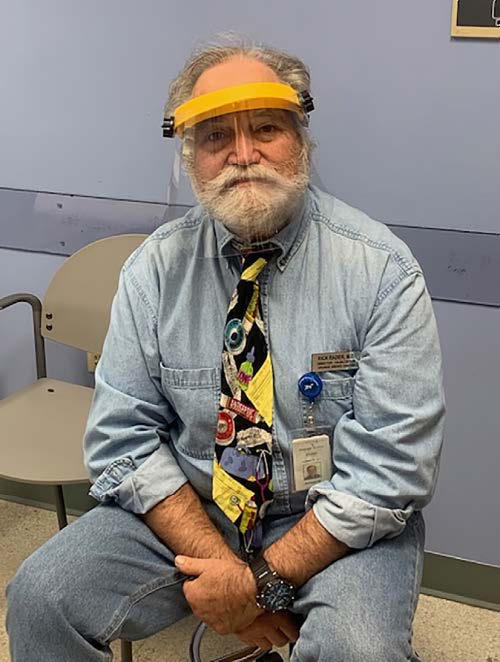

TIES THAT BIND: (Left) Dr. Rader appears on the August 1994 cover of EP alongside Orange Grove Center patient Kelly Bankston; (Above) A recent photo featuring the same necktie from his extensive collection. While EP is celebrating its 50th anniversary; Dr Rader is celebrating more than 25 years at EP Magazine.

In 1971, the dark and stormy nights began to fade. The three founding editors of Exceptional Parent Magazine found a mission, "to provide practical guidance for the parents of exceptional children." Dr. Maxwell J. Schleifer, Dr. Lewis B. Klebanoff, and Dr. Stanley D. Klein described their venture:

"This is The Exceptional Parent… a magazine created to deal with the issues many of you have been struggling with for long and so patiently – the frustrations, disappointments and yes, the triumphs of raising a child with a disability. For many years, we, the editors of Exceptional Parent, in our clinical and administrative work with disabled children and their families, have experienced similar frustrations, disappointments, and triumphs. At the same time, each of us has attempted to share our experiences at parent and professional meetings, on radio and television, and in published reports. More than two years ago, The Exceptional Parent was conceived as a forum for the mutual sharing of the acquired knowledge of both parents and professionals. Their enthusiasm encouraged us in our knowledge. To the best of our knowledge, a magazine of this nature has never been attempted. From our struggles with the first issue, we are aware that we need your help. We need your suggestions, criticisms, and contributions, where you are as a parent, a professional, a person with a disability – or perhaps, all three. We believe that we need to share with each other, to learn from each other, and to grow together."

State of Editorial Purpose: "Child-rearing is a vital and difficult task, unrecognized as such and unsung, perhaps, because it is so universal. Even more vital and much more difficulty is the task of raising a child with a disability. Much progress is being made in the understanding and habilitation of those afflicted with all of the major disabling conditions of childhood. Sadly lacking in these efforts is any coordinated system of translating these findings into meaningful form for parents. Practical, human, daily questions as well as issues of longrange, planning, care and financing are what you will find in the pages of The Exceptional Parent. Technical information stripped of professional jargon and practical advice on day-to-day care will share these pages with many special features, including ideas from our readers. Our goal is to help you to share with us the view that the child is our main concern, that disability, however severe, is secondary."

In 1994, I read a seductive ad in the Journal of the American Medical Association. An unidentified community agency was interested in supporting a physician to help forge the future of healthcare for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Like most (all) physicians at the time, I did not receive any formal training in treating patients with disabilities. We saw them in our clinics, but not because of their disabilities, but as a consequence of them (deferred care, misdiagnosis, diagnostic overshadowing, and indifference). It was intriguing, challenging and attractive.

While I was clueless about the field (or what passed for the "field" at the time) I had a track record in stress medicine, medical innovation and new medical initiatives (pharmacoeconomics, social medicine, medical informatics, physician education). I couldn't resist, and luckily, neither could they. I found myself as the new Director of the Morton J. Kent Habilitation Center at the Orange Grove Center in Chattanooga; established in 1953 by parents who refused to accept the advice of the day, "Send him to an institution and concentrate on the normal ones." They didn't and created a celebrated and progressive community for people with intellectual disabilities, their families, and others who watched and imagined its potential for replication.

My role was like something from Star Trek – "go out into the world and beg, borrow, steal or create new ways to improve

A GOLDEN LEGACY : FIFTY YEARS OF INNOVATION, CHANGE AND TRIUMPH

In no special order (and with sole responsibility for anticipated omissions), we have seen the following "big ticket items" that have brought new heights to people, families and communities with disabilities:

Universal newborn screening • Recognition of people aging with disabilities • Evolution of the medical model to the social model • The rise of the Direct Support Professional • The Orphan Drug Act • National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities • Surgeon General's Conference of Health Disparities of People with Mental Retardation • Special Olympics Healthy Athletes Programs • The American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry • Recognition of autism and its growth • Dementia and Down syndrome • National Council on Disability • Self advocates movement • Family Voices • Recognition of mitochondrial disease • Financial Planning • Project DOCC • Katie Beckett • "Voice of the Retarded" • Boy Scout Merit Badge on Disability Awareness • President's Committee on People with Intellectual Disabilities • National Leadership Consortium on Developmental Disabilities • Individual Education Plan • ANCOR • Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association • National Association on Dual Diagnosis • Special Care Dental Association • Montreal Declaration • Willowbrook State School scandal • Social Role Valorization • Normalization • Ableism • University Centers of Excellence in Developmental Disabilities • American Association on Health and Disability • Golisano Foundation • WISH Foundation • Settings Rule • Self-determination • Supported Living • Assistive technology •Sensory Processing Disorder • Unfunded mandates • Hyperbaric oxygen therapy • Inclusion • Mainstream education • Council for Exceptional Children • Autism Speaks • UN Declaration for the Rights of People with Disabilities • Supported Decision Making • Autism Self-Advocates Network •Applied Behavioral Analysis • Christmas in Purgatory • Organ Transplants in People with Intellectual Disabilities • Americans with Disabilities Act • Olmstead Act • Cochlear implants • Crisis Intervention Training for Law Enforcement • Implantable medical devices • Not Dead Yet • Mothers From Hell • Recognition of U.S. Military Exceptional Family programs • World Congress on Disability • Human Genome Project • The Fetus as Patient • Unified Sports of Special Olympics • Brain Banks • Simulated patients with disabilities • Positive Exposure • National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practice • Multi-Sensory Environments • American Academy of Developmental Medicine • Project Accessible Oral Health • Physician Decision Making • End-of-Life Care for People with Disabilities • Desensitization • Retirement • Sex Education for People with Disabilities • Genetic Testing • HIPPA • Adaptive Sports • Recognition of Fragile X •The Arc of the United States • AUCD • College Opportunities for Students with Disabilities • Simon Foundation for Continence • Religion, Spirituality for People with Disabilities • Positive Behavioral Supports • Robotic Education in Autism • "Meaningful day" • Active Treatment • End of Sub-Minimal Wages • Habilitation Model • Sib Shops • American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities • Female Health Initiatives • Preventive Health Strategies for People with Disabilities • Programs to Document and Teach About Eugenics • Changing Faces • The rise of single syndrome support groups • College courses on Stigma • State Councils on Developmental Disabilities • The "Medical Narrative" • Pet therapy • Equine assisted therapy • Service animals • Practice Without Pressure • Music Therapy • Art Therapy • Dance Therapy • Play Therapy • Electronic Communication Devices • Medically Underserved Population Designation • Mobility Devices • Accessible Transportation • SMART Homes • Grief counseling for People with Disabilities • Transitions • The Patient Experience • Grandparents as Caregivers • Micro-enterprises • Inclusion International • Different Brains

And, to the other countless groups, movements, innovations, challenges, initiatives, programs and best practices which we have had both the pleasure and opportunity to report on over the past 50 years… thank you for allowing us the privilege of covering you in Exceptional Parent Magazine.

the lives of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities." The stipulations of my contract were indeed novel. I asked for a parking spot (being from New York, this was quite the perk), permission to wear jeans, and to act as a free-range chicken for a year to learn about the field, the culture of Orange Grove, needs, resources, challenges, syndromes, and how key champions in the field viewed obstacles, innovation, and sustainability. I had no time to waste and realized I needed to learn some key terms, phrases and history. I took advantage of attending a conference at the University of Wisconsin and signed up for as many sessions as I could. I was overwhelmed, intimidated, and relieved that my attendee badge announced that this was my first time at the conference. I probably didn't need the badge to announce my virginity; my bewildered expression was a dead giveaway.

On the afternoon of the last day, I attended a session conducted by Dr. Klein. During the Q & A session, I had posed several questions that announced I was both a novice and thirsty to know more. I insisted on responding to his answers with the question, "But why can't that happen?" At the end of the session, we sat down for a cup of coffee and I explained my new position and my excitement. I shared with him my latest venture of recruiting individuals with intellectual disabilities as "simulated patients" and having medical students and residents learn about their "conditions," their lives and their humanity. It was the first time this was ever attempted and Dr. Klein invited me to write an article about the project. He had me at "write."

Several months later, I was scheduled to present the results of my first year to the Orange Grove Advisory Board that was assigned to evaluate my contributions, my potential, and any accomplishments. They were true to their word of giving me unbridled free range for a year (it was a leap of faith for both of us) to get my footing in this new initiative. The day before the meeting, I received a package from Exceptional Parent Magazine. It was several copies of the latest issue. The cover story was my article of a "new twist to playing doctor" (See page 5). My debut of introducing "simulated patients with intellectual disabilities" at Grand Rounds at the Chattanooga Branch of University of Tennessee College of Medicine-Erlanger Hospital was a huge success. It resulted in the adoption of a curriculum for fourth year medical students during their rotations at Erlanger Hospital.

At the meeting with my Advisory Board, they posed the expected question, "Well it's been a year, why should we keep you?" I reached into my book bag and handed each of them a copy of the new issue of Exceptional Parent Magazine (with my cover story and picture). Along with the magazine were a stack of letters from prestigious medical schools interested in replicating the program. I started to publish articles in Exceptional Parent Magazine and, in 2000, following the passing of Dr. Maxwell J. Schleifer, was appointed as the Editor in chief, a position I continue to be both humbled and inspired to hold.

The year 2021 marks the 50th Anniversary of Exceptional Parent Magazine (now called EP Magazine for short). It is the oldest, most respected, and continuously published resource for the disability community. The magazine has "grown up" with the disability rights movement and has chronicled the progress, the luminaries and the achievements of the grass roots organizations, the mom-and-pop start-ups, and the inclusion of people with disabilities. The past half century has seen remarkable progress in medical achievement, legislation, technology, and human potential. Exceptional Parent Magazine has supported and reported on the key events, milestones and "mountain moving" movements that have reshaped the world for the disability community.

Exceptional Parent Magazine has evolved. What was once exclusively dedicated to parents is now universally read by all the stakeholders in the disability community. Parents started to tear out articles from the magazine and brought them to their appointments with doctors; they slapped them down on the desks and asked (often with tears in their eyes), "Why didn't you tell me about this?" This was cutting-edge information and often, even the doctors were unaware of these new programs, new treatments, and new potentials. They began to subscribe to Exceptional Parent Magazine, they began to submit articles, and began to provide those to their families. No longer primarily a magazine for "parents" the P began to reflect the physicians, the providers, the professionals, the partners… and even the payers.

Several years ago, I was reminded of just how significant EP Magazine was to countless families. A woman called me and introduced herself. She was a physical therapist and mother of a son with cerebral palsy. She recently retired from her practice (specializing in children with disabilities); her son had passed away in his early 40's but she continued to subscribe to EP for another 20 years. She wanted to donate her entire collection of EP Magazine, over 400 issues, and said that while EP Magazine was a great source for "new" information… every day, the parent of a child with newly–diagnosed, disabling conditions becomes an "exceptional parent." And much of the information is timeless, "new" to "new" parents, and worth their weight in reassuring them that they are not alone. Here's to another 50 years of insuring that exceptional parents do not have to face even one "dark and stormy night." •

ANCORA IMPARO

In his 87th year, the artist Michelangelo (1475 -1564) is believed to have said "Ancora imparo" (I am still learning). Hence, the name for my monthly observations and comments. – Rick Rader, MD, Editor-in-Chief, EP Magazine Director, Morton J. Kent Habilitation Center Orange Grove Center, Chattanooga, TN