ANNUAL HEALTH CARE ISSUE

HEALTH DISPARITIES REVISITED

BY LAUREN AGORATUS, M.A.

Health disparities affect underserved populations more than their peers, resulting in increased morbidity and mortality. This article will examine health and other related disparities, from a Life Course perspective (i.e. over the lifespan).

According to AMCHP (Association of Maternal/Child Health Programs), the Life Course "is a theoretical model that takes into consideration the full spectrum of factors that impact an individual's health, not just at one stage of life (e.g. adolescence), but through all stages of life."1 It is noted that both race/ethnicity and disability status are factors that put children and adults at risk for health disparities.

Let's start at the Beginning

According to MCHB (Maternal/Child Health Bureau),2 black infant and maternal mortality is three times higher than peers. Recent state and national initiatives are seeking to address this. In addition, the NJ Hospital Association national conference on the uninsured found that families without coverage were AfricanAmerican followed by Hispanic families. This means that children and adults with serious illness are diagnosed on average 2-4 years after their insured counterparts, when a disease is costlier to treat or in some cases untreatable. In early intervention, which covers children with disabilities from birth to age three, underserved families were Hispanic followed by Asian families according to NECTAC (National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center, now the Early Childhood TA Center).3 Research shows that early intervention is key to best outcomes throughout the lifespan.

moving through chiLdhood

Additional disparities exist in the diagnosis of autism and other developmental disorders. Blacks followed by Hispanic children are diagnosed much later than peers, when intervention would have had better results earlier.4 In schools, African American children are more likely to be misclassified as needing special education. They do not receive services under I&RS (Intervention & Referral Services) prior to classification, do not receive as many services, or receive services for a shorter time. Black children are more likely to be sent to separate settings rather than the "least restrictive environment" required by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.5 The GAO (Government Accounting Office) Report showed that black children, especially boys, and students with disabilities are subjected to unequal disciplinary procedures. This also includes the inappropriate use of restraints, seclusion, and other aversive interventions, which result in injuries or even death.6

aduLts and disparities

The Commonwealth Fund noted that the three main indicators of health were heart disease, breast cancer, and stroke. Although it is noted that longitudinally mortality rates decreased overall, the gap between black and white patients increased.7

A recent article in Health Affairs cited that the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in more than twice the mortality rates for black and Hispanic families.8 During the pandemic, recently the Washington Post article highlighted race and disability in Covid treatment. Visit the site: washington- post.com/health/2020/07/05/coronavirus-disability-death.

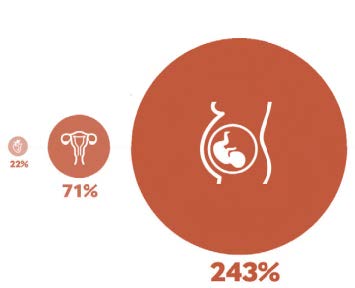

WIDENING GAP: A black woman is 22 percent more likely to die from heart disease than a white woman, 71 percent more likely to perish from cervical cancer, and 243 percent more likely to die from pregnancy- or childbirth-related causes.

The National Council on Disability issued a statement on the passing of an African American man who was denied care due to his disability perceived as lacking "quality of life".9 There is discrimination in consideration for organ transplants based on race,10 sex, age, and disability.11 Lastly, even for palliative or end-of-life care, including hospice, there are disparities.12

puLLing it aLL together: sociaL determinants of heaLth

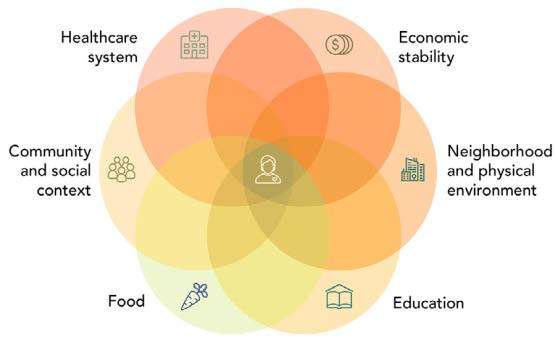

The upshot of all this is that disparities can occur literally from birth to death. One consideration that adversely affects health disparities are the Social Determinants of Health. Besides access to health care, other factors affecting health include "socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks".13 The American Academy of Pediatrics recently recognized the importance of these factors particularly affecting children with special needs. In addition, children and adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities have been recognized as an underserved population affected by health disparities. Various studies have shown that expectations and bias affect outcomes.

A STARK CONTRAST: Families without healthcare coverage lead to children and adults with serious illness being diagnosed on average 2-4 years after their insured counterparts, when a disease is costlier to treat or in some cases untreatable.

recommendations

The Arc National has an excellent position statement on fairness in health care, which could apply to various underserved groups. The statement addresses:

- • Access: This includes wellness and physical accessibility to the office and testing equipment.

- • Discrimination: There is misperception on interventions or even denying care. For example, a parent of a three-yearold with Down syndrome was asked by doctors if they should give antibiotics to her toddler who had pneumonia, a completely treatable condition.

- • Affordability: Many individuals with disabilities live in poverty. Healthcare must be affordable or, if they rely on Medicaid, services must be comprehensive. • Communication and personal decision making: Some individuals with disabilities may have difficulty communicating but should still have supports that don't take away all their rights (i.e., use supported decision-making instead of guardianship). See resources for information on supported-decision making. Recommendations from other organizations include:

- • Providers must be aware of implicit bias while treating patients so that all are treated fairly. Some programs match medical students with families of children with special needs from diverse backgrounds to help improve their understanding of the challenges faced by families from different backgrounds and with different cultural expectations and practices.

- • Pediatricians can screen for social determinants of health at regular visits.

- • Data must continue to be collected on existing disparities to enhance quality improvement.

- • Families and self-advocates can advocate for their needs (See EP "How Self-Advocates and Families can Deal with Health Disparities Affecting People with Disabilities," reader.mediawiremobile.com/epmagazine/issues/204297/viewer?page=57).

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH: The American Academy of Pediatrics recently recognized the importance of these factors particularly affecting children with special needs. In addition, children and adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities have been recognized as an underserved population affected by health disparities. The upshot of all this is that disparities can occur literally from birth to death.

The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health14 cited systemic strategies to reduce racial inequalities in healthcare. These included creating communities of opportunity by focusing on early child development, reducing childhood poverty, enhancing employment opportunities, and improving housing. Another strategy was addressing delivery of healthcare, including enhancing access and focusing on primary care, quality of care, social risk factors, and a diversified health workforce. Thirdly, building policy to address inequities includes raising awareness, building political support, increasing public concern, enhancing individual and community capacity, and finally, dismantling racism and discrimination.

Health disparities based on race/ethnicity or disability must be addressed. This can be done on both an individual and a systemic basis. Only then will disparities and discrimination be eliminated, improving healthcare and health outcomes for all.•

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Lauren Agoratus, M.A. is the parent of a young adult with multiple disabilities. She serves as the State Coordinator for Family Voices-NJ and as the central/southern coordinator in her state's Family-to-Family Health Information Center. FVNJ and F2FHIC are both housed at the SPAN Parent Advocacy Network (SPAN) at spanadvocacy.org

References

- 1. amchp.org/programsandtopics/LifecourseFinal/Pages/default.aspx

- 2. mchb.hrsa.gov/maternal-child-health-initiatives/healthy-start

- 3. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3138901

- 4. cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/addm-community-report/differences-in-children.html

- 5. understood.org/en/community-events/blogs/the-inside-track/2018/05/23/faqs-on-racial-disparities-in-special-education-and-the-significant-disproportionality-rule

- 6. gao.gov/products/GAO-18-258

- 7. commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2018/sep/focus-reducing-racial-disparities-health-care-confronting

- 8. healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200625.389260/full/?utm_source=Newsletter &utm_medium=email&utm_content=Racism+++COVID-19&utm_campaign=HAT+7-2-20&

- 9. ncd.gov/newsroom/2020/ncd-chairman-statement-michael-hickson-death

- 10. unos.org/news/racial-equity-in-transplantation

- 11. aappublications.org/news/2020/04/20/transplant042020

- 12. sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/12/171218090939.htm

- 13. kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/

- 14. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6406315