ANCORA IMPARO

RICK RADER, MD ■ EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

On the Sensibility of Playing at an Off-Off-Off Broadway "Production"

Off-Off-Off Broadway "Production" Out of the 40 dentists who enthusiastically came into the lecture hall, 35 were already actively seeing and treating patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities. They came to see who else joined the camp… and they came to identify themselves as dentists who knew the joy of embracing this marginalized patient population.

I have always been amazed at how music impacts and manipulates the emotion, energy and pulse of a theatrical production. For years they have released the music score from plays, musicals, and movies. Sometimes the music becomes better known than the production it was created to enhance.

Since the earliest days of the theatre, music has been the cornerstone of the theatrical enterprise. Theatrical music has changed the heart rate and rhythm of the audience. Everyone is familiar with their own experience with the "earworm," a song or melody that you can't get out of your head. They typically enhance the dramatic narrative and the emotional impact of the scene in question. In its own way, music from Broadway has been a mainstay in the chronicles of leading us to somewhere else.

So I get into my car to drive to the Chattanooga airport to catch a flight to New York City. I turn on the radio and it begins,

They say the neon lights are bright On Broadway They say there's always magic in the air On Broadway But when you're walking down the street And you ain't had enough to eat The glitter rubs right off and you're nowhere On Broadway

And of course I'm no stranger to the Drifter's version of the popular song "On Broadway." It was a major chartbuster in the early Sixties. And while the song reveals the harshness of trying to become a Broadway star, it has a positive upbeat ending.

They say that I won't last too long On Broadway, on Broadway I'll catch a Greyhound bus for home, they all say On Broadway But no, no they're wrong, I know they are I can play this here guitar And I won't quit till I'm a star On Broadway I'm gonna make it, yeah On Broadway I'll be a big, big, big man On Broadway I'll have my name in lights On Broadway

And while I was not on my way to Broadway I was on my way to the Big Apple, the West Side of town, 11th Avenue to be precise. I was going to the Jacob Javits Convention Center, the mother of all conference centers. The Javits Center is a goliath. It has over 760,000 square feet of exhibit space and neverending rows of classrooms, conference and meeting rooms and it certainly can be considered the "Broadway" of exhibit, trade and educational conferences. And while it's "off-Broadway" it certainly doesn't take a back seat to anywhere else.

The term "Off-Broadway" is actually a precise term; and not restricted to any specific address or location. An Off-Broadway theatre is any professional theatre venue in Manhattan with a seating capacity between 100 and 499. Some shows that premiere Off-Broadway are subsequently produced on Broadway. Originally the term "Broadway" referred to any theatre that was within a defined geographic box on or around Broadway. The switch to the term "Off-Broadway" was related to paying a lower salary to the union members for performing and working in smaller venues. Its history dates back to the 1950's and according to theatre historians, "Off-Broadway" offered a new outlet "for poets, playwrights, actors, songwriters, and designers."

PREACHING TO THE CHOIR: Out of the 40 who enthusiastically came into the lecture hall, 35 were already actively seeing and treating patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

And then there's "Off-Off-Broadway." This category of theatres started in 1958 with a "complete rejection of commercial theatre." Off-Off-Broadway theaters are smaller than Broadway and off-Broadway theatres, and usually have fewer than 100 seats. In a way, I was slated to appear in an "Off-Off-Broadway production."

I had both the honor and challenge of co-presenting at the Greater New York Dental Society's Annual Meeting. This is not a local, regional or state meeting. This is, in fact, the largest dental conference in the world. It typically attracts over 50,000 dental health providers who come to learn the newest procedures, techniques and treatments for dental and oral health. There are over 600 companies that exhibit the latest in materials, equipment, diagnostics, appliances, tools and strategies designed to improve the outcomes for people with oral health needs.

I was part of an all-star quartet including Dr. Jack Dillenberg, the doyen of Public Health Dentistry and a driving force in teaching dental students about special needs dentistry; Maureen Munnelly Perry, DDS, MPA, MAEd, Professor of Special Care Dentistry and the Director of the Center for Advanced Oral Health at the Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health; and Neal Romano, the Chairman of the National Council on Disability.

We were charged with promoting, encouraging and incentivizing dentists and dental hygienists to treat patients with disabilities, especially those with intellectual and developmental disabilities. This was no small task considering that few dental schools in the United States mandate or provide any formal, competency-based training in this high-risk population.

Of course, our three-hour session was not the only option for the 53,000 dentists. The 200-page meeting guide listed an array of courses, lectures, workshops and seminars on a variety of topics. There was a myriad of subjects and presented a ton of options for the dentists to choose from.

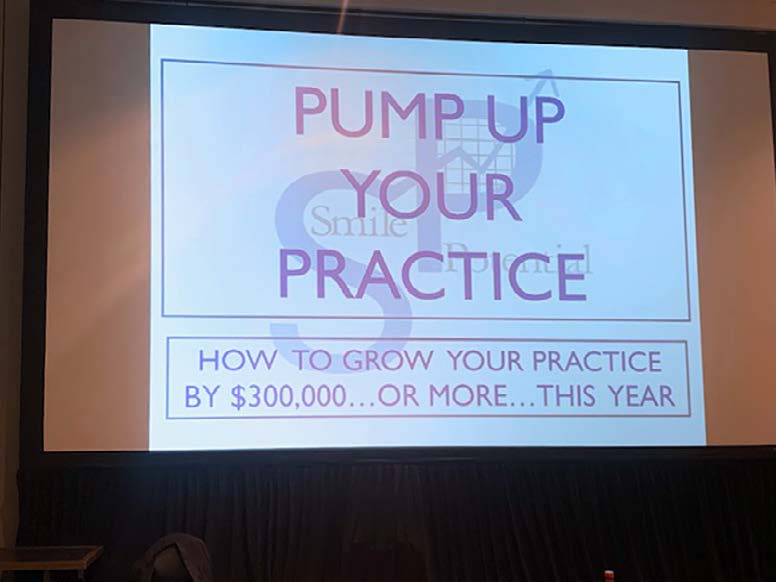

When our session was ready to begin, I left our meeting room to get a cup of coffee to get through the morning. On the way back to begin our presentation, I put my head into the room adjacent to ours and gasped when I saw the title slide for the scheduled class:

"PUMP UP YOUR PRACTICE: HOW TO GROW YOUR PRACTICE BY $300,000…OR MORE…THIS YEAR"

MIGHT VS RIGHT: How do you compete with an invitation to the road to riches versus the obstacles of treating complex patients?

It dawned on us what we were up against; a true David vs. Goliath ordeal. How do you compete with an invitation to the road to riches versus the obstacles of treating complex patients? Patients who may not understand you, cooperate with you, appreciate you, pay you, remember you, and who may assault you. But before we made our pre sentation, we realized we needed an audience. The very thing the producers of "Off-Broadway" and "Off-Off- Broadway shows" needed. If "Off-Off-Broadway" shows had room for under 100 and under 50 respectively, we were thinking this might be considered, "Off-Off-Off Broadway." While there were 53,000 potential attendees, the grim reality of low attendance was palpable.

While it was no surprise, it was still disappointing that only 40 dentists showed up. That is .75% (less than one percent). Out of the 40 who enthusiastically came into the lecture hall, 35 were already actively seeing and treating patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities. They came to see who else joined the camp, they came for camaraderie, they came for validation, and they came to identify themselves as dentists who knew the joy of embracing this marginalized patient population. That left us with a target audience of five dentists who we had the opportunity to encourage learning more about these folks, their needs, and their lives.

This is certainly not a condemnation of dentists. Their training and dedication provide them with the right to earn an attractive living. In fact, the high overhead of operating an active practice requires it. I want this to be thought of more like a "cautionary tale." If dentists don't take up the mantle to care for, and about this population, it will eventually become a condemnation of dentists for not honoring and committing to the code of ethics that distinguishes the practice of dentistry.

The four of us performed like troopers. We were as enthusiastic in sharing our passion, our experiences, and our vision as if all 53,000 dentists crowded into that room. Our reward, our justification, and our motivation were all based on the hope, the feasibility, and the potential that we converted all five of those curious dentists. Perhaps we succeeded, and perhaps all five of them will eventually encourage five more dentists to climb aboard.

All four of us left the lecture room, as a quartet, harmonizing like the Drifters, from our first performance in an "Off-Off-Off Broadway production."

And I won't quit till I'm a star on Broadway, on Broadway On Broadway (on Broadway) I'm gonna make it, yeah (on Broadway) I'll be a big, big, big man (on Broadway) I'll have my name in lights (on Broadway) Everybody, everybody's gonna know me, yes (on Broadway) All up and down Broadway (on Broadway)•

ANCORA IMPARO

In his 87th year, the artist Michelangelo (1475 -1564) is believed to have said "Ancora imparo" (I am still learning). Hence, the name for my monthly observations and comments. – Rick Rader, MD, Editor-in-Chief, EP Magazine Director, Morton J. Kent Habilitation Center Orange Grove Center, Chattanooga, TN