Normal's time is up. It has got to go. In truth, the only normal people are people you don't know very well. The moment you get to know another human being – really know them, see them, not how they should be, but how they actually are – it is not their normality that matters. It's their differences, eccentricities, fallibilities, strengths, and weaknesses that constitute their humanity.

BY JONATHAN MOONEY

When I was a kid, I was the round peg that did not fit in the square hole that is school. I was the kid who had such a hard time sitting still in elementary school, I grew up chilling out with the janitor in the hallway; I couldn't keep my mouth shut so I grew up on a first name basis with Shirley the receptionist in the principal's office. I also had such a hard time with reading, specifically reading out loud, that I spent most of the day hiding in the bathroom with tears streaming down my face. I did not learn to read until I was 12; I was diagnosed in third grade with a whole bunch of language-based learning disabilities and attention disorders. I left school for a time in sixth grade. I struggled with anxiety, depression, and had a plan for suicide.

Like many young people who don't fit a narrow definition of "the normal student" or human, I faced a lot of low expectations. I was told I would never graduate from high school, would be unemployed, and even at one point was told I would end up incarcerated. I beat those odds. Opposed to being a high school dropout, I became a college graduate. Opposed to being unemployed, I ended up writing books, the first of which I wrote as an undergraduate in college. Instead of being an inmate, I became an advocate on behalf of people with atypical brains and bodies.

This journey of transformation often raises a valid question in people's minds. I'm asked all the time by parents, teachers, and people with differences how did I do it? What drugs did I take and where can they buy some? While the answer to that question is multifaceted and complicated, I do know that I transcended these low expectations in large part because of my mom. To give you a mental image of Colleen Mooney: my mom is not a tall woman. On a good day in high heels on her tippy toes, she is 4' 11". My mom also has a very high-pitched voice like Minnie Mouse. And, by the way, she curses like a truck driver.

So if you were a teacher, principal, or a counselor not doing right by her son, you did not want cursing Minnie Mouse in your office! But when I was having a hard time in school that's where my mom was every day. How did I know she was in that office? Because every dog in the neighborhood was running away! Glass was shattering! Only bats could hear her high-pitched obscenities.

My mom understood that I didn't need somebody in my life to fix me; I needed somebody in my life to fight for me. There is a deeply held cultural belief that has become institutionalized in schools and the helping professions, that people with atypical brains and bodies are deficient and in need of fixing. This belief stems directly from the myth that there is a normal brain or body that everyone should have and if you deviate from this mythical human something is wrong with you. My mom fought against the relentless focus on my deficits and the relentless emphasis on fixing me.

When I was a kid, like many people and atypical brains and bodies, I had many variations of an individualized education plan or IEP. The NSA, the KGB...they got nothing on the IEP. They did deep intel on me, flew drone missions over my house, and it wasn't good news in that file. Many researchers, including Thomas Hehir, Director of Special Education at the U.S. Department of Education, and now a professor at Harvard, have shown that these documents are relentlessly deficit oriented. For every strength or talent cataloged there are often 20 weaknesses. This systems orientation to what's wrong with atypical children leads to a pedagogical and "rehabilitation" practices and interventions that are all about fixing them.

My mom fought against this fix-the-kid mentality in every way but nothing was a bigger fight then spelling. Every Friday when I was in elementary school was spelling test day. What a wonderful way to end the week. Every day, leading up to Friday, was fix-my-spelling day. What a wonderful way to spend the week. I got my words on Monday and did two hours of flashcards; Tuesday I drew the words in the sand; Wednesday I built the words with blocks; and Thursday… I did interpretive dance to get the words in. Come Friday… I failed the test. My mom constantly advocated for me to have accommodation on these tests. It did not happen. So on Friday we ditched school and went to the zoo because I loved animals, to construction sites because I loved building, and to the movies because I loved stories. She called this focus-on-what-is-wight-with-you day. Cumbersome title, I know, but it saved my life.

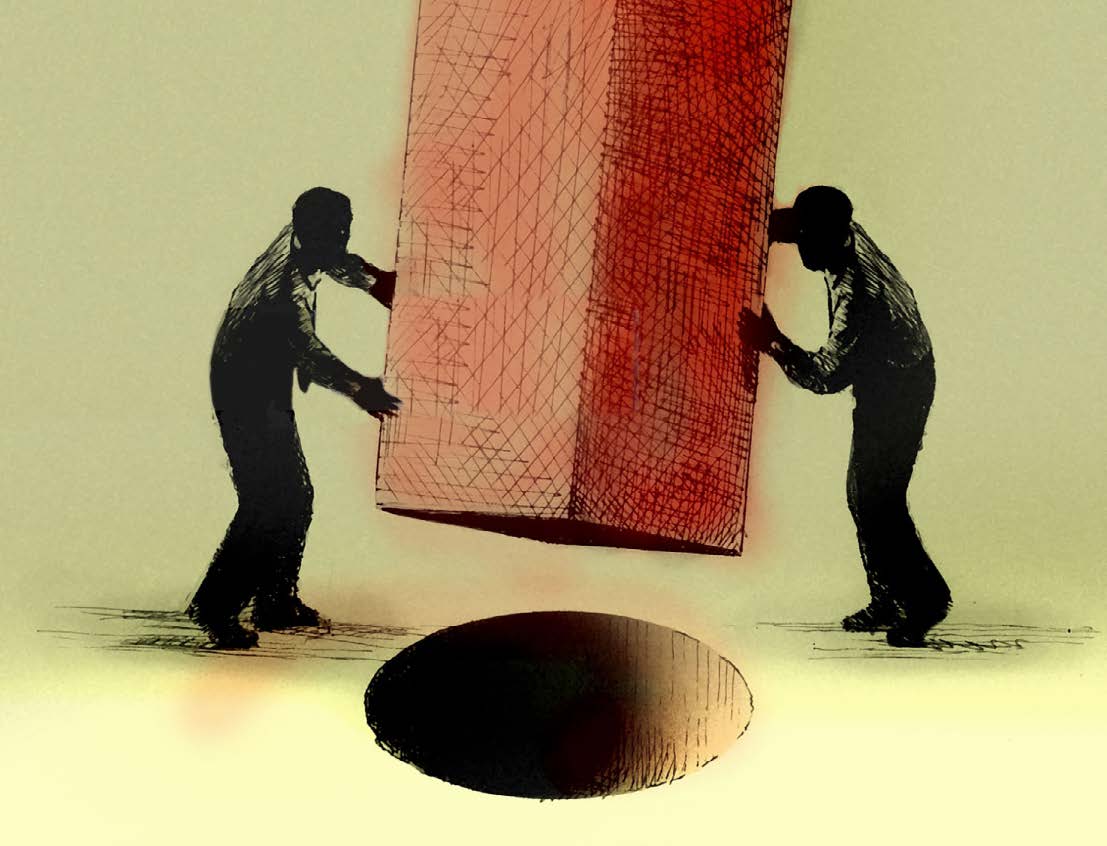

My mom rejected this medical deficit model. My mom fought for the idea that if a student doesn't learn the way they are taught, then it's the school's obligation to teach the way they learn. It's not the person that should change but the environment around them. It is wrong to ask anyone to be different than who they are. It is an act of violence to work to make the round peg fit the square hole. Every human being has the right to be different. We should demand that our systems and institutions include not just some human beings, but all.

My mom was fond of saying to me "normal sucks." She was right, because what is normal anyway? Look up normal in any English dictionary and the first definition is "usual, regular, common, typical." How did this become something to be aspired to and have the cultural force it has? Normal has a history and it is not a history of discovery, but a history of invention. It was born in the mid-1840s with the rise of standardization, industrialization, and statistics. I didn't do too well on my AP statistics class (ok, didn't even take it!) but I do know that averages are by definition abstractions. A statistical norm doesn't exist in the world—it is an aggregation of multiple differences on a curve. The normal or average birth rate for women in America: 2.5. Haven't seen many half babies in my life. Ian Hacking summed it up when he wrote, "The normal whispers in your ear that what is normal is also right."

Normal has been responsible for a great number of social injustices. Because of this idea, whole groups of people have been labeled as abnormal or sick and their subjugation justified as "treatment." In the 19th century, black folks who were enslaved and ran away to escape this injustice were diagnosed with "slave running away sickness." Up until the mid-20th-century, actual doctors and psychiatrists diagnosed women as suffering from hysteria and this diagnosis was used to justify their disenfranchisement; and homosexuality was listed in the DSM as a personality disorder until the 1970s. Oh yeah – one more – let's not forget eugenics. In the early 20th century a bunch of scientists, geneticists, doctors, and social workers were so enamored by the idea of normal that they decided to rid the world of "defectives."

Normal's time is up. It has got to go. In truth, the only normal people are people you don't know very well. The moment you get to know another human being – really know them, see them, not how they should be, but how they actually are – it is not their normality that matters. It's their differences, eccentricities, fallibilities, strengths, and weaknesses that constitute their humanity.•

From the book Normal Sucks: How to Live, Learn, and Thrive Outside the Lines by Jonathan Mooney. Copyright © 2019 by Jonathan Mooney. Reprinted by permission of Henry Holt and Company.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jonathan Mooney's work has been featured in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Chicago Tribune, USA Today, HBO, NPR, ABC News, New York Magazine, The Washington Post, and The Boston Globe, and he continues to speak across the nation about neurological and physical diversity, inspiring those who live with differences and advocating for change. His books include The Short Bus and Learning Outside the Lines.

- Title: Normal Sucks: How to Live, Learn, and Thrive Outside the Lines

- Author: Jonathan Mooney

- Publisher: Henry Holt and Company

- Publication Date: August 13, 2019

- Paperback: 233 pages ISBN-13: 978-1250190161

- Available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com