CHRISTINA LLANES MABALOT

"I" In Aniridia

In December of 2013, I gave in to my husband's suggestion of having my eyes enucleated. After recovery, my outer appearance reflected the inner beauty of a heart that had courageously thrived through pain, especially from people's adverse reactions to someone who looked different.

My rare disease, aniridia (Greek for the absence of the iris), made me feel like an outcast. My eyes were dull and strange-looking, not only because of the involuntary movements (nystagmus) but also due to my habit of sticking my face into whatever I needed to see, just like a cartoon detective would, but without a magnifying glass. Don't get me wrong; it's not as if I would have easily blended among my peers without it; I'm an oddball by nature. Sadly, I did not have a lot of people to talk to. I'd usually have mental conversations with myself, and there were times when I answered audibly, which made me appear crazy.

"Why are you kissing the paper?" my second-grade homeroom teacher asked me on the first day of school. Born with a gift for annoying people, I retorted, "Because I love it!"

I knew I was in trouble! My furious teacher commanded me to stand facing the wall at the backside of the classroom. I wondered why my teacher asked me that question in the first place, even though my mother previously had a long conversation with her about my extremely "nearsighted" vision, which everybody thought was my only disability. My visual acuity classified me as legally blind, which is familiar to most people with aniridia, but deep inside of me, I knew for sure that I had other eye-related problems.

I felt self-conscious of the involuntary eye movement, so I rehearsed keeping my eyes still in front of a mirror. I did not know that the practice made my eyes appear like they had no pupils, so children may have thought I was a ghost. I had photophobia, and the glare from some lights made me blind as a bat at daytime. Every Monday morning, when the school's flag ceremony was held at the grounds instead of the corridors next to the classrooms, I would close my eyes to ease the pain caused by the sunlight. One time, I was left behind on the grounds, not realizing that all the students had marched to their respective classrooms. On another occasion, several years later, I was at a cocktail party wherein strobe lights made me squint. A young man in that party even tried to pick me up saying, "You look like you've had one too many drinks."

"Every Monday morning, when the school's flag ceremony was held at the grounds instead of the corridors next to the classrooms, I would close my eyes to ease the pain caused by the sunlight. One time, I was left behind on the grounds, not realizing that all the students had marched to their respective classrooms."

Later, I learned that "aniridia syndrome" is a rare disease. With aniridia, while lack of an iris may cause light sensitivity, the real problems are the conditions which "make up" this syndrome that can cause loss of the remaining vision and other complications.

Frequent headaches eventually landed my name in the school's regular absentees list. My headaches were so severe I imagined the angel of death locking my head under his feet. I was so immobilized I couldn't get up nor open my eyes. I found out later that "glaucoma," or high intraocular pressure (IOP) was the culprit for this killer pain. Glaucoma, one of the multiple eye conditions of aniridia syndrome, is one of the leading causes of blindness among patients. Thus, it is essential to have all aniridic children's eye pressure checked at birth and every six months after that to keep it under control, because escalated eye pressure can eventually damage the optic nerve.

I was about nine years old when my siblings and I started taking pills and applying eyedrops to keep our eye pressure under control. We were prescribed "Diamox" (brand name for Acetazolamide), a medication that has several side effects including electrolyte imbalance. Diamox made me urinate every ounce of energy in my body. Initially, I loved how it made me skinny, so that it was hitting two birds with one stone; regulating eye pressure and weight loss – but eventually, I hated that the treatment made me emaciated and dysfunctional after some time.

The doctors also warned that while eyedrops regulate our IOP, its long-term use would eventually cause the opacity of lenses, consequently reducing the passage of light to our eyes and, sooner or later, our vision. It was a "damned if you do, damned if you don't" situation, but I'd risk my lenses over suffering through killer headaches anytime.

At some point, my parents chose to discontinue the eyedrops, supposedly to prevent opacity of our lenses, but what we did n't know then was that since we were all born with subluxated (dislocated) lenses, opaque lenses shouldn't have bothered us. Nevertheless, the outrageously expensive medications and visits to the ophthalmologists were draining our finances.

When eyedrops were available, administering them were bonding sessions for me and my three siblings with aniridia. The four of us, side-by-side on my parents' kingsized bed, teased and mocked one another; our laughter buffered the sting of the medication.

I felt that my absenteeism was certified once the root cause of my headaches was medically established. I remember pretending to suffer from a glaucoma attack on days when I couldn't get up for school because I was talking to my boyfriend on the phone overnight. My unsuspecting parents would write an excuse letter and I'd get off the hook. My baby brother, however, didn't have it that easy. Like me, he frequently couldn't get up for school because of his escalated eye pressure, although some days I think it was because he watched TV all night. I knew, because we frequently ran into each other at dawn, both doing our own thing. Regardless of the real reason, my parents brought him to the ophthalmologist every time he suffered headaches.

One unforgettable day, the ophthalmologist suggested laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI), a surgical procedure to decrease my brother's IOP. It entailed making an opening through the iris to allow fluid to flow directly to the frontal chamber of the eye. My father used to preach against surgical procedures, knowing from his extensive research that such may cause our loss of vision. Stuck in a loop of medical bills, doctor visits, and checkups, he desperately gave in. I am still bewildered to this day as to why he agreed that my brother go through the surgery; this was a bitter pill to swallow for my father. The complexity of our medical condition was beyond us. Summing up having no iris, legal blindness, subluxated lenses, nystagmus, corneal scarring, close angle glaucoma, cataracts meant that we had only a small chance of surgical success. After the unsuccessful surgery, my father's interaction with the family slowly declined. He distanced himself from us, distressed by the new reality he and his family had to face.

It was one thing after another from that point. Since my brother never recovered from that surgery, he had to drop out of high school. Finally, ophthalmologists had to enucleate (remove) my brother's eye to restore his quality of life. Only then was he able to continue his education. This incident scarred my heart to believe that aniridia is a "catch-22" situation; I either maintain low vision and deal with its miser able complications or I give up my eyes for a pain-free life.

A turning point for me was when I finally decided to come to terms with aniridia years later, when I had my own family. We participated in the 2007 "Make a Miracle" medical conference and the "Make a Difference" clinic hosted by the Aniridia Foundation International (AFI). Aniridia Foundation International is a 501(c)3 nonprofit charitable organization dedicated to assisting those with low vision or blindness due to aniridia. On the first night of socialization, I was astounded to shake hands with so many "aniridics" in all forms and stages of life. Before that night, I felt our family's case was isolated because I hadn't ever met anyone else with aniridia. It was both a comfort and a pain to realize that these people could identify with my experiences. The mystery that enshrouded aniridia slowly unveiled as I confronted this sphere of reality in my life.

The free clinic did make a difference when Dr. Edward Holland declared that my left eye, which was then blind but still had a healthy optic nerve, may have a chance to see again through the stem cell transplant technology – but the procedure required the stabilization of the intra-ocular pres sure. Nevertheless, this ray of hope compelled me to preserve my eye by resuming medication for a good six years.

It was around 2010 when my left eye started bulging out—and, my right eye, as if in rebellion for not getting as much attention, simultaneously began to shrink. My face appeared so lopsided I never left home without my sunglasses, even when it was dark. The angel of death was resurrected, oppressing me with headaches more severe than those I suffered during childhood. My cockeyed appearance slowly took over my inner self and my disposition went back and forth from congenial to depressed while my heart became sick from deferred hope.

Finally, in December of 2013, I gave in to my husband's suggestion of having my eyes enucleated. After recovery, my outer appearance reflected the inner beauty of a heart that had courageously thrived through pain, especially from people's adverse reactions to someone who looked different.

THE SEEING "I"

In hindsight, looking through the eye of aniridia, I saw a world distorted by optical filters of different ocular conditions. From afar, people looked similar, varying only in height, clothing, size, bearing, and length of hair, while places were merely outlined by structures, streets, lights, and concrete objects that looked abstract. In that world of optical illusions, I would run to hug a strange woman whom I thought was my mother, mistake a clump of hair for a dead rat, frequently board a wrong bus or vehicle, and accidentally invade the men's restroom. It was a life marked with pain, shame and obstacles which reminded me of a society where I didn't belong.

Beyond aniridia, however, the seeing "I" perceives through my heart. It is a world beyond vision, one with exciting challenges, opportunities for growth, golden lessons, and life that aims for significance.•

SETTING SIGHTS HIGH: The author's daughter Jem was born with aniridia. "She was blessed to have talented doctors, as well as being introduced to the Aniridia Foundation International, a non-profit organization committed to studying and researching aniridia, to stop the progression of the condition and help people who are visually and medically affected by it."

A WORLD BEYOND VISION : UNDERSTANDING ANIRIDIA

According to VisionAware.org, the term aniridia is Greek for "without iris." It is a congenital, bilateral (both eyes) condition characterized by the complete or partial absence of the iris. Doctors usually spot aniridia when the newborn has dark eyes with no color in the iris, the ring around the pupil.

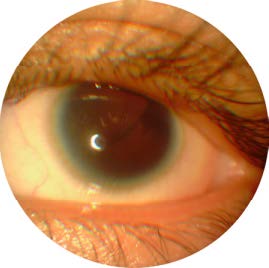

EYES HAVE IT: (Above) A close of photograph of Jem Mabalot's eye reveals the partial absence of the iris. Treatment of aniridia prioritizes maintaining the patient's residual vision.

Growing up, my siblings and I were diagnosed as legally blind and sensitive to lights. However, as we matured, many other eye issues were identified, like subluxated lenses, nystagmus, corneal scarring, closed-angle glaucoma, and cataracts, conditions which are associated with aniridia. With several eye issues found in a single patient associated with aniridia, these complicating factors make it challenging to achieve the primary goal of the treatment of aniridia, which is to maintain the patient's residual vision.

Aniridia results from a genetic mutation that affects the PAX6 gene, which is responsible for the formation and maintenance of the eye. However, now we also know that it plays a significant role in the development of many parts of the body, including the pancreas, central nervous system, olfactory system and parts of the brain. Thus, some patients with aniridia syndrome live with medical issues such as diabetes, autism spectrum disorders and metabolic problems, among others, which usually occur in their childhood.

The mutation of the PAX6 gene may occur sporadically, which means that neither of the parents has the aniridia syndrome, but once it occurs, it may be passed down into each successive generation. Every person with aniridia syndrome will have a 50 percent chance of producing a child with aniridia.

This unfortunate statistic became true for my daughter, who was born with aniridia. But despite having the same visual impairment as mine, her circumstances have been favorable here in the United States. She was blessed to have talented doctors, as well as being introduced to the Aniridia Foundation International, a non-profit organization committed to studying and researching aniridia, to stop the progression of the condition and help people who are visually and medically affected by it. Visit make-a-miracle.org to learn more about aniridia.

HEARTSIGHT Christina Llanes Mabalot is physically blind from aniridia, but has a vision. She enjoys touching people's lives to bring out the best in them. "Heartsight" explains her ability to see with her heart. Christina earned her B.A. degree and Masters in Education from the University of the Philippines, Diliman, specializing in Early Intervention for the Blind. She later received Educational Leadership training through the Hilton-Perkins International Program in Massachusetts, then worked as consultant for programs for the VI Helen Keller International. She has championed Inclusive Education, Early Intervention, Capability Building and Disability Sensitivity programs. She was twice a winner in the International Speech contests of the Toastmasters International (District 75) and has been a professional inspirational and motivational speaker. Christina is blissfully married to Silver Mabalot, also physically impaired, her partner in advancing noble causes. Their children are Paulo and Jem, who has aniridia.