PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS TO THE AAIDD ANNUAL MEETING

There is always a solution to any problem; some solutions take time, some solutions take money, some solutions require collaboration, some solutions require courage, some solutions require logic, some solutions require divine inspiration; nevertheless, a solution is there.

BY ELIZABETH A. PERKINS, PHD, RNLD, FAAIDD, FGSA

There has been justifiable concern that principles and values, and hard-fought rights and key legislation that directly impacts the disability community, have all come under significant threat, due to fundamental shifts in the priorities of the current administration.

It is an honor to be here today to welcome you to the 142nd annual meeting of AAIDD and to discuss the conference theme of "Reaffirming Diversity and Inclusion." This statement can conjure up many different meanings, hopes, and wishes – and I would like to share my thoughts for how we can collectively contribute to promoting diversity and inclusion, so that it becomes more of a reality tomorrow than it is today.

I am confident that you will find the presentations and posters that you will see during the course of the conference to be informative. Hopefully, they will give you new ideas and alert you to resources that you can utilize in your workplace. You will have the opportunity to learn about new research findings, innovative programs, evidence-based practices, policy considerations, and new interventions that can be applied across many domains. The common thread is that they are all ultimately aimed at improving quality of life. And beyond that, if you haven't already become a member of the AAIDD family, or this is your first time you've attended our conference, we will be doing everything in our power to convince you it should be the first of many!

The theme Reaffirming Diversity and Inclusion was chosen in reaction to troubling events, actions, and divisive rhetoric – leaving many of us with considerable anxiety. There has also been justifiable concern that principles and values, and hard-fought rights and key legislation that directly impacts the disability community, have all come under significant threat, due to fundamental shifts in the priorities of federal agencies under the current administration. Unfortunately, there are several examples – the continuing efforts to dismantle the Affordable Care Act, or possible limita tions to be introduced to the Americans with Disabilities Act, and even proposed funding cuts for Developmental Disabilities Act entities such as State Developmental Disabilities Councils. Unfortunately, these are a small sample of many more.

Through effective and persistent advocacy, I am relieved that some of these challenges have not yet come to fruition. However, we can never have the luxury of letting our guard down. Underscoring many of these issues, is the need to reaffirm our commitment to the diversity and inclusion of all people, but especially the civil and human rights and supports of the people for whom we are all here today, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities…our friends, our family.

SPEAKING SENSE: Dr. Liz Perkins at the 142nd Annual Conference of AAIDD; "[We] need to reaffirm our commitment to the diversity and inclusion of all people, but especially the civil and human rights and supports of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities."

My Story

But first – Who is this person standing before you? I realize as I look around that I see many familiar faces, but many more I do not know. So before I speak directly about diversity and inclusion, please permit me some time to introduce myself. I am a great believer in the power of storytelling. I developed a love of musicals from my mother from watching American musicals as a youngster. Don't be alarmed, I shall not be using interpretative dance, but perhaps you may have heard of a hit Broadway musical called Hamilton? So let me begin… "How does an armless, gray-haired, big gay nurse, from Kingswinford, a town in Middle England no one's heard of, by providence, emigrates to Florida, and shocker, is now a PhD, and a scholar?" Yes – I too was born this way, and I was born that way too, and perhaps that's enough! As I clearly can't sing as well as CHARIS – I'll spare the rest of the Hamilton-esque rap. But let me elab orate. as I am incredibly humbled that you, the AAIDD membership, elected an English gay nurse with a disability to serve as the President of this prestigious association that was founded in 1876. It is certainly not something I ever expected when I arrived here twenty years ago!

So let's think about expectations and the power of expectations. When I was born, I was quickly whisked away by the nurses, and my mother didn't see me for several hours. Eventually, the doctor came on the ward and said, "Mrs. Perkins have you seen your daughter yet?" After she replied that she hadn't and was obviously worried, the doctor quite dismissively informed my mother that, "well she has one arm a little shorter than the other," and promptly had me brought to her. My mother upon seeing me, who was already a little disturbed by the turn of events, was shocked. Her expectation from the doctor's unfortunate and imprecise choice of words had led her to believe that I had two arms, with one just a little shorter (with a hand, elbow etc.) and certainly not the absence of most of it! A few days later, my mother was given sage advice from a nurse who told her that everything would be fine, "just let her find her own way of doing things," she said. And because of that – I grew up to be fiercely independent and did not shy away when something challenged me. It was never, no I can't do that, rather it was, "well, let's figure this out."

School life was a happy experience for me, both socially and academically. I actually had very little contact with, or awareness of, other children or adults with disabilities throughout my early years. And you may notice that I don't wear a prosthetic arm. I have always felt that they hindered me more than helped me. But the good doctors in the National Health System in England would insist on sending me for fittings every couple of years. And, yes, I'd wear them for a couple of weeks and then they'd end up in the back of the closet. Actually, I got more use from my prosthetic arm as a comedic prop. When my older sisters had friends over, I'd throw it into the middle of the room they were in and say "Can I lend you a hand?" – or hide it in the toilet bowl. My sisters, like Queen Victoria, were not amused. I distinctly remember a few times when a detached hand would be hurled back at me. The last time I had one fitted was when I was eleven, at which point I refused to go for any more appointments. I used to get annoyed and think to myself, why are you constantly trying to fix me? I'm not broken… this is me!

My first recollection of when I truly felt different, or recognized that others perceived me as being different, was during the first few months of high school. A new self-awareness dawned on me, due to a lot more gawking stares and some cruel remarks, but as I've often found – humor was my way of "disarming" people; don't groan! Humor was my way to make other people feel comfortable. I had also by that time realized that I was gay. Although my friends and family would find this hard to believe, I was actually very apprehensive about what my future would be having a disability and growing up gay in the 80's – not to mention having to contend with the 80's big hair! But seriously, I was certainly not aware of the term "intersectionality" back then and yet had three marginalized identities, a woman, who is gay, and disabled.

The brief career counseling I received in high school had encouraged administrative jobs and that I should register as disabled – playing it safe I daresay! So that's what I did for a while. My father, in seeking a new use for a property he had, that was currently used as a nightclub and Indian restaurant, had decided to open a small residential care home for older adults in 1986. I mourned the loss of the regular Chicken Tikka Masala, but it opened up a new career opportunity I hadn't considered before. It was to become the first registered nursing home in my hometown of Kingswinford. And it still remains the oldest operating in the area to this day. My sisters and several of my cousins worked there too…very much a family business, and being part of a family that became family to others was something we all strived for.

I loved being a care assistant, equivalent to what we know here as a direct support professional, and subsequently enjoyed the administration side too, as the company expanded. I was always acutely aware that I was a visitor to the home of people that used our services, and the positive daily impact we could make on their quality of life. My love for my job was so noticeable that the registered nurses I worked with had, on several occasions, told me that I should do my nurse training. So, wanting to pursue further education, the point came when I decided to give it shot.

In early 1989, I applied to the local nursing school for their general nursing course, and I was excited to be called for an interview. That excitement didn't last, and I felt I was the subject of mere amusement by my interviewer, who shared his concern that it might make him look bad if I couldn't complete the training. One of the most bizarre questions he asked was "Who dresses you on a morning?" For sure – I've never been a fashion victim – but I was in no doubt by what he meant by that remark. A few minutes later I was met with the same incredulity by the occupational health nurse, who immediately remarked that he anticipated many issues. He simply couldn't fathom how I would be able to do CPR? I went home very dejected, and couldn't quite believe how curtly I had been treated. I was not a potential student. I was not even a person. I was, in fact, a potential problem!

Call it fate, or just an amazing coincidence, but within a couple of weeks of the anticipated – but very politely worded – rejection letter, there was an advertisement in the local newspaper for student nurse applicants for training at Lea Castle Hospital, in Kidderminster, in Worcestershire – yes, where the original Worcestershire sauce comes from! This was training to work specifically with people with intellectual disabilities, what is referred to as learning disabilities in the United Kingdom. It is a branch of nursing that is actually celebrating 100 years in 2019. I wrote another application and anticipating similar reservations, wrote the most compelling a letter that I could muster. It was basically asking just for the opportunity, the opportunity to prove myself capable. The interview I had couldn't have been more of a contrast. And perhaps that was my first real experience of being an advocate.

I met with the then Senior Nurse Tutor, Sue Carmichael, at Lea Castle School of Nursing. She admitted that my application was unusual, no surprise there, but then suggested a plan to see if this was feasible, was this possible? The plan was to hire me as a nursing assistant for two weeks during which time I would work on the ward with the most medically complex people with intellectual disabilities. I was as unfamiliar with people with severe and profound disabilities, and people with significant physical disabilities, as you could imagine. Yet here I was assisting with their activities of daily living and personal care, for which my nursing home experience had prepped me well. But I still remember feeling unprepared, shocked even, my first time bathing a person with cerebral palsy, with spastic quadriplegia, with severe scoliosis and contractures, who was non-verbal with profound intellectual disability. That shock I felt soon abated, and having exposure to many people with different types of disability, soon familiarized me, and galvanized in me the determination to become a nurse with a disability for people with intellectual/developmental disabilities. This mission resonated deeply within me. This experi ence also taught me a valuable lesson of how it felt to be apprehensive when first interacting with a person with a significant disability. I had always been on the receiving end of that dynamic before.

During that two weeks I was certainly put through my paces, as I was concurrently assessed by the ward sister, charge nurse, occupational health nurse, and the occupational and physical therapists. They independently and collectively assessed how I would do certain things, such as my lifting techniques (I was actually very strong in my left arm), opening glass vials, drawing up injections, etc. The Friday afternoon of my first week, Sue contacted me and said "You're in." I was elated! And a few months later I was in the August 1989 cohort of RNLD student nurses beginning our training. Oh, and by the way, along with my cohort, I got my CPR certificate in the first month of training. In 1992, I had apparently become one of the first registered nurses to qualify with my type of disability in Great Britain. Sadly, Sue had been promoted to a new position and had moved away by the time I actually started my training. She went on to be the lead for Complex Health Needs of Britain's Valuing People initiative for the UK's Department of Health. We were reunited after 21 years at a Health Summit in Washington, DC, where Sue was an invited speaker. She told me she had often recounted my story. She also confided that she actually had felt bad about the mini-work trial and she had learned from other colleagues that I had emigrated to the USA. I guess keeping track of the "one-armed nurse" was easy to do!

It's a small world, and I know for a fact that some of you in the audience today were also present at that very meeting. The point is that Sue was the disability professional that gave this disability professional with a disability, dignity and respect. She is entirely responsible for setting me along on my career path and giving me the "dignity of risk" (Perske, 1972), and giving me the opportunity to prove myself.

Training was no cakewalk, but the thing I found to be most frustrating was that wall of uncertainty I was met with at the start of each new placement. However, as it became common knowledge, the novelty of the "Liz – the one-armed student nurse" wore off, and I eventually became just "Liz – the colleague" and the "Liz – the staff nurse" and so on. It was the repetitive process of making the unfamiliar become familiar; making the unfamiliar familiar. This is a mantra I have taken through my professional life with me.

Making the Unfamiliar Familiar

So let's fast forward – one aspect of my current role includes educating health professionals about appropriate care and support to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. I know firsthand (never second hand, mind you – another groan) about how attitudes and stigma result in preconceived and inaccurate beliefs and knowledge about what people with disabilities can and cannot do. All too often the focus is on what cannot be done. Folks with disabilities are a creative group of people because we have to constantly find alternate solutions for completing a task. We have to use tools or navigate environments that have often overlooked or not even considered abilities that differ from their design parameters. Any left-handers in the audience – raise your hand. My fellow lefties, you can agree how awkward is it to use scissors designed for right-handers? Am I right?

I also know that apprehension, and fear of the unknown, can result in feeling uncomfortable around someone who is perceived as being "different" or "unusual" or "atypical" for whatever reason. Unfortunately, such discomfort can go to an extreme, especially when the differences are heightened by others' fears, ignorance, and, yes, bigotry. The result is people become prejudiced, phobic, and intolerant – stigmatizing people with IDD, with ableism, along with racism, sexism, ageism, homophobia, religious intolerance or fundamentalism. Ignorance and bigotry distort perspectives of what is the true reality of a person, or groups of people – denying them equality, dignity, and respect. It is tragic that the true reality of their talents, and the contributions they can make to our society educationally, socially, vocationally, and politically, are sidelined. When one views the world simply as "them and us", it is a world that can never be truly united and inclusive. But often awkwardness, fear, or prejudice can only be alleviated through experience and interaction, by communicating with each other, learning about each other, and learning from one another. We are all but the sum of our experiences and our knowledge and our own biases. To paraphrase Scottish empiricist David Hume, we are nothing but bundles of perceptions (Hume, 1739).

Technology is changing our world. Social media is a powerfulforce, though we know it can be used and unfortunately abused. However, the connectivity it can create to bring people together, highlight injustice, organize and motivate advocacy, and increase visibility to include people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and issues that directly, and disproportionately impact them – the power to do that is invaluable. It can certainly serve as a proxy for real-world experience, especially where there has been limited opportunity for such interactions. The breakthrough for many people usually occurs from a personal experience, a personal connection, a friendship that forms, or circumstances that bring people together, in ways that wouldn't usually occur, and it is that experience that changes hearts and minds about someone who is perceived as different or other, from what our preconceived biases and stigmas may hold.

The Stigma Cycle

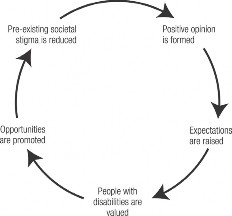

In my lectures, I present what I call the Stigma Cycle – very much informed by my personal experiences (see Figure 1). For whatever reason, a negative opinion has formed, which results in lowered expectations. If you have lowered expectations, the person with a disability is devalued; if you devalue the person, opportunities are denied or removed entirely, and the result is a self-sustaining personally held stigma, which collectively contributes to the maintenance of a larger societal stigma. And as we have witnessed throughout history, and continue to witness, if prominent people uphold such stigmas… it can continue to infect the minds of others and spread like a contagion.

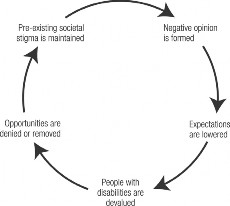

In my lectures, I present what I call the Stigma Cycle – very much informed by my personal experiences (see Figure 1). For whatever reason, a negative opinion has formed, which results in lowered expectations. If you have lowered expectations, the person with a disability is devalued; if you devalue the person, opportunities are denied or removed entirely, and the result is a self-sustaining personally held stigma, which collectively contributes to the maintenance of a larger societal stigma. And as we have witnessed throughout history, and continue to witness, if prominent people uphold such stigmas… it can continue to infect the minds of others and spread like a contagion. How do we break the stigma cycle (see Figure 2)? If we focus on the positive, on a person's assets and talents, rather than assumptions about the challenges, if we raise our expectations, a person with intellectual and developmental disabilities is valued. Opportunities are then promoted, and the result is that pre-existing societal stigma will be reduced. We all are potential advocates to do this, be it for ourselves, or on behalf of others. Just imagine the collective impact that has been made by everyone here today! Imagine the collective impact we can have tomorrow and continue to do so in the future…to eventually eradicate stigma.

As members of AAIDD, you represent a variety of professional disciplines; you represent every state in our great nation; you may represent many nations around the globe; you represent direct support staff, administrators of agencies and providers, policy makers, health care professionals, educators, and so on. The list is lengthy. My point is that you may be the person who raises the expectation and confronts the risk. You may have been the only person who could or would raise the expectation. And think of the ripple effect, the action one person can take, the difference one person can make! And don't ever doubt that one person can make a difference, or that one person can have courage against what may seem insurmountable odds.

FIGURE 1: The stigma cycle; As we have witnessed throughout history, and continue to witness, if prominent people uphold such stigmas, it can continue to infect the minds of others and spread like a contagion.

Breaking Down Preconceived Expectations

I want to think back to when I started my training in the 1980s— do you think that the expectation would be that a person with Down syndrome would learn to drive a car? Far from it; the expectation from Jon's pediatrician was that he wouldn't even want toys to play with. Jon passed his driving test at the first attempt (Down Syndrome Center, 2013). Did we expect that a person with Down syndrome can be champion weightlifter? Or a fashion model? People with Down syndrome who have hypotonia (floppy muscle tone)? Well tell that to John Stoklosa (Hartman, 2013). He started out in Special Olympics, reached the pinnacle by being World Champion and now competes in regular competitions. Or Madeleine Stuart (McNab, 2015) who after losing 44lbs decided she would like to become a fashion model, and subsequently became one of the first models with Down syndrome to appear on the runway at New York Fashion week. In the 1980s would there be the expectation that people with Down syndrome would themselves become parents (Ewert, 2012), or become teachers of American Sign Language (Ortega-Cowan, 2017), or run a marathon (Goldberg, 2013), or even climb Mount Everest (Coughlan, 2013)? Probably not, and yet here we are!

FIGURE 2: Breaking the stigma cycle; Imagine the collective impact we can have tomorrow and continue to do so in the future to eventually eradicate stigma.

And by the way – this is not "inspiration porn" as the great and sadly missed Australian advocate Stella Young would say (and if you haven't seen her TedTalk on the subject you are missing a treat!). This is not a parade of people with disabilities who are so brave for merely being born this way, or having overcome their disability. They are examples to people to be applauded because of their notable achievements contrary to all expectation, or that lowered expectation. Each one has raised the expectation bar higher so just think of the future opportunities and future achievements we will see.

My Nephew Joe: The importance of raising expectations hit homes to me personally, professionally and with my family, too. As I mentioned earlier, prior to my nurse training, there was no one in my family with IDD. Then along came my nephew Joe. To be sure there have challenging times, and challenging behaviors, and as many with autism find, the teenage years were particularly difficult for him and my family. But Joe, along with his family, had high expectations, and he was determined to live independently as soon as he could.

Following school, Joe went to a small college for young adults with intellectual and behavioral difficulties. As part of that program, he started as a volunteer in general maintenance/gardening at a residential care home (not my family's), and he learned to ride public transport independently. He is pretty adept at taking selfies, too! He is now serving an apprenticeship at that care home and serves as a back-up bingo caller there too. He is furthering his education by taking horticulture classes at a local college. Joe lives independently in his own home. He will be 22 years old on Thursday. He expected to do the same things as his older brother and sister did. And as with all of us, he has tried things he didn't like, and the first place he lived independently, he didn't like. But having opportunities to try different things, to make different choices, and just being able to change ones' mind, these were key. I am truly proud of him and his achievements. He actually moved out of his parent's home at a younger age than both his brother and sister. He was determined to do so and achieved that milestone when he was 18! My family's personal caregiving experiences with Joe, along with our experiences of caring for our grandmother with Alzheimer's, have given me invaluable insights over the years that augmented my formal education and knowledge as a health care professional and future researcher.

Expectations of others can be limiting, but the expectations that we place on ourselves can be just as self-limiting. More so, if a society devalues us…We must therefore always encourage the people we support to have goals and dreams. Life is for living, but we need to have a motivation and drive. After all, dreams can't come true if we do not encourage them to exist in the first place. In the end, that's what we are all striving for – to improve the quality of life and well-being. These terms I have used often in my own research, for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. I really prefer "contentment" with life.

Diversity

So now let's consider diversity and inclusion. What is the definition of diversity? According to the Miriam-Webster Dictionary it is the condition of having or being composed of differing elements: variety; the inclusion of different types of people (such as people of different races or cultures) in a group or organization ("Diversity," n.d.).

Perhaps some of you recognize Kim Peek? Dustin Hoffman's character in 80's film Rain Man was based on Kim. He observed, "Recognizing and respecting differences in others, and treating everyone like you want them to treat you, will help make our world a better place for everyone," (as cited in Peek, 1996). The great Dr. Temple Grandin also had a succinct but very powerful point to make about being different. She said, "I am different, not less." And another famous doctor, Dr. Seuss said "Why fit in when you were born to stand out?"

Are We Reaffirming Diversity and Inclusion?: For our association and the field, we need to truly embrace diversity – the inclusion of the different race/ethnicities, different cultures, different religious/spiritual communities, different generations, and the LGBTQ community, that is represented by the people with IDD that we assist, and we need to expand the diversity of professionals we have who support them. My old mantra – to make the unfamiliar familiar – is what we see with disability awareness training. But is awareness what we want? Do we want to be disability-friendly? We see initiatives that promote being autism-friendly, etc. But is friendliness what we want? Some programs are now promoting acceptance but is acceptance truly what we want?

I would like to see a world in which terms like diversity and inclusion are not a goal or a lauded ideal but a reality. Programs to promote awareness, friendliness, or acceptance are no longer needed and become irrelevant. We are here, we are who we are, no explanation beyond that is necessary. So what if we were born this way or became this way?

Labels that we are given by others or, indeed, that we attach to ourselves, should not be limiters but merely a descriptor of an important attribute, and shouldn't be considered our only identity. We also need to recognize that affiliations to such labels can wax and wane throughout our lives. We must be careful that these labels do not overshadow the person, or confine their actions. We shouldn't make assumptions.

I ask you – does our field truly acknowledge, consider, and embrace the diversity and intersectionality of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in every aspect of their lives where professionals can contribute to their contentment? What about minorities within minorities? We really should because we still have much to do to ensure equality. Let me illustrate with the following example.

As a gerontologist, I have an interest in life expectancy. One of the most glaring studies that highlighted disparity I have ever come across was by Yang, Rasmussen and Friedman that was published in The Lancet (one of the world's most prestigious medical journals) in 2002. The encouraging news was that for Americans with Down syndrome, between the years 1983 to 1997, their life expectancy had risen to 49 years of age overall. In fact, for White Americans with Down syndrome, it was 50. But for Black Americans with Down syndrome it was just 25 years, and other races, a mere 10 years. Such differences should be horrifying, and an outrage, and yet many in our field remained unaware, and remain unaware. And beyond our field – not a chance! As a professional organization, do we have diversity in our membership, do we have diversity in our leadership? If not, why not? AAIDD is a place where you can get involved and develop your leadership skills. This room has luminaries in the field, AAIDD past-presidents, board members, fellows, but who will come forward to serve the Association? Our board should represent you, but it can't if you do not put yourselves forward for leadership roles, Raise your expectation – you can do it! Take the risk! Some of us naturally seek leadership roles, but some of the best leaders have needed a nudge or two along the way.

Inclusion

So let's consider inclusion. For me, the true measure of inclusion is when someone's disability becomes irrelevant but their participation is expected and assured. The same with all those other aspects that make us different, diversity enriches our lives. When one views the world as "them and us," it is a world that can never be truly united and inclusive. What makes us different should not define us, and should never serve to divide or confine us!

So today reaffirm with me your commitment to diversity and inclusion and continue on our journey together. I am certainly no Pollyanna; yes, we are used to uphill battles; yes, we are used to diminishing resources; yes, we are used to the frustration that obvious needs are not being met; yes, we know that many supports are not readily available, that needed research is not getting funded or prioritized. We are also weary of changing political landscapes. We are weary that progress is incremental, never exponential. We long for a fair and equitable comprehensive health care system that provides continuous services across one's entire life without arbitrary age-defined interruptions and breaks in service. Not waitlists, not excuses, and certainly not penalizing people for pre-existing and lifelong conditions.

We need to recharge our determination to uphold fundamental human rights and the hard-fought gains and supports that contribute to improving life for people with IDD and their family caregivers. It is critical that we need to find renewed vigor to press ahead. We can use our collective voice for collective goodwill. We can help empower people with disabilities to advocate, share the knowledge professionals need to provide optimal supports, provide data to the policy makers, and though perhaps we are not all leaders, we can all certainly contribute, and all do our part to make a difference. On July 26, 1990, George H.W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) into law, He said, "Let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down!" Twenty-eight years later and there are still walls of exclusion. We still have many barriers to break, and furthermore, we must be vigilant to stop the creation of new walls. We need to continue staunch and sustained advocacy in whatever manner we feel that we can do that, one-on-one, in our workplaces, on a local level, state, regional, or national-level. Collectively, we will do so to support our friends, our families, our colleagues, and our community. We must make sure people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are never overlooked, or worse still, blatantly ignored, or WOMP, WOMP, openly ridiculed! There is always a solution to any problem; some solutions take time, some solutions take money, some solutions require collaboration, some solutions require courage, some solutions require logic, some solutions require divine inspiration; nevertheless, a solution is there. Let us not fall victim to apathy, or to anger, or fear – there is always a way! The solutions you find will change and improve lives, and it is our privilege to have the ability to do so. Be audacious with your ideas. Remember the late great Maya Angelou said, "If one is lucky, a solitary fantasy can totally transform one million realities."

My desire to have a conference theme devoted to Reaffirming Diversity and Inclusion, was to ask for your help, for you to present and demonstrate how you and your colleagues affirm diversity and inclusion in your work, in your programs, and in your research. I am so excited that so many presentations truly reflect this theme!

Last year I became a naturalized American citizen, and as an immigrant, I want to say that I believe in the goodness of the people of America, and I believe in the American Dream. Reaffirming diversity enriches lives, challenges our beliefs, sparks our creativity, celebrates our differences and connects us to each other. It is the cornerstone of promoting inclusion. So as I conclude my remarks, please know that we are your AAIDD family, and we are here with you, and we are here for you. Thank you for listening – and welcome again to our 142nd meeting! •

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Dr. Elizabeth A. Perkins, PhD, RNLD, FAAIDD, FGSA, is Associate Director and Research Associate Professor at the Florida Center for Inclusive Communities (FCIC), at the University of South Florida's (USF) - University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities. She is the current President of AAIDD (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities). She has a PhD in Aging Studies and a BA (summa cum laude) in Psychology, both from USF. Dr. Perkins is also an RNLD, a registered nurse from the United Kingdom, where she trained specifically in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). Her clinical experiences have been predominantly in the field of geriatric and residential care. Her current areas of interest include health aspects of aging with IDD, quality of life issues of older family caregivers of adults with IDD, and compound caregiving (when older caregivers have multiple caregiving roles). Dr. Perkins can be contacted at eperkins@mail.usf.edu.

References

Coughlan, M. (2013). 15-year-old Eli Reimer becomes first person with Down syndrome to reach Mt. Everest's base camp. Retrieved from people.com/celebrity/eli-reimer-is-first-person-with- down-syndrome-to-reach-mt-everests-base-camp/ Diversity. (n.d.)In Merriam-Webster's online dictionary. Retrieved from merriamwebster.com/dictionary/diversity. Down Syndrome Center. (2013). How Jon learned to drive. Retrieved from downsyndrome- centre.ie/how-jon-learned-to-drive Ewert, K. (2012). Mothering a child with a disability: The secret thoughts part one. Retrieved from kristaewert.com/2012/01/30/mothering-a-child-with-a-disability-the-secret-thoughts-part- one/ Goldberg, E. (2013). First runner with Down syndrome completes NY marathon, redefines word 'champion'. Retrieved from huffingtonpost.com/2013/11/04/new-york-marathon-down-syn- drome_n_4214496.html. Hartman, S. (2013). Meet a superhero with a soft touch. Retrieved from cbsnews.com/news/meet-a-superhero-with-a-soft-touch. McNab, H. (2015). 'If people could see that beauty is on the inside then most of the models in the world would have Down syndrome': Meet the inspiring young woman with a genetic condition determined to change the face of beauty. Retrieved from dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3081890/If-peo- ple-beauty-inside-models-world-syndrome-Meet-inspiring-young-woman-genetic-condition-determined-change-face-beauty.html Ortega-Cowan, T. (2017). Happy advocate. Retrieved from tcpalm.com/story/specialty-publi- cations/vero beach/2017/07/26/happy-advocate/454236001/ Perske, R. (1972). The dignity of risk and the mentally retarded. Mental Retardation, 10, 24–27. Peek, F. (1996). The real Rain Man. Salt Lake City, UT: Harkness Publishing Consultants Yang, Q., Rasmussen, S.A., & Friedman, J. M. (2002). Mortality associated with Down's syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: a population-based study. Lancet, 359, 1019–1025