CHRISTINA LLANES MABALOT

The Heart of a Special Needs Mom

What if mother hadn't modelled selfless love in our everyday life? Then I would not have had the heart or courage to raise my own children in a similar fashion, especially my visually-impaired girl. Needless to say, I built on mom's successes.

My hand found hers. It was shockingly cold and bony. The strong hands that used to hold, guide and teach me how to do things had become shriveled and deformed. Seventeen years before we were reunited, those hands could still drag me out of bed whenever I had lazy-itis. Now they felt like they could break with a mere handshake. I lifted her out of her rattan chair to hug her. The frail, tiny woman in my arms did not feel like my mother at all.

Suddenly, she shrieked my name in delight. Already totally blind and in the advanced stages of Alzheimer's, mom amazingly discerned it was me – enough evidence that this mother's memory of her child withstood mental and physical feebleness.

I was guilt-stricken, thinking of all the pains I had caused her in the past which may have resulted in her extreme deterioration. I teased her, "What did your children do to you?"

"You mean, look what YOU did to me!" she snarled accusingly.

She rambled on about her children, which conjured for me mental pictures of this frail woman's significance in her accomplished children's lives. Flashbacks flooded my mind, along with admiration and wonder: what if my mother, Isabel, had not chosen to have more babies because her first child was visually impaired? I thought of my oldest sister, who would become a social worker for the vocational rehabilitation center in her hometown. I thought of my two brothers who are Adaptive Technology experts; and yours truly, one who lives to advocate for excep tional people. My only sighted sibling helped mom support all of us through college when he served and progressed in the US Navy. With mom's choice to have us all, one could say the special needs community is a little better today.

What if my mother didn't advocate for our admission to regular schools? She certainly wouldn't have burned the candle at both ends. Likewise, her visually-impaired kids wouldn't have struggled as much – but perhaps we may not have turned out as well rounded.

My mother would rise early each day to help four visually-impaired children get ready for school. Preparation included fixing a good breakfast, ironing uniforms, packing lunches and snacks, and the most challenging – getting us out of bed. Then when all her children had left for school, she'd tackle household chores. She, an elementary school teacher, barely had time to write lesson plans for her classes. She made dinner in the evenings when the family was reunited. Then she would read to all her four visually-impaired kids in the order of good behavior. I was always the last to be read to. Reading times extended sleep. This was her back-breaking routine. Occasionally mom had to go to school to meet with teachers to explain how her son or daughter needed more time to fin ish a project or paper due to visual impairment. School field trips sometimes required her presence when we were younger, and she would be absent from work to be our sighted guide. "Blind dates" with mother as a chaperone was a reality in our family. She took us to most of our have had the heart or courage to raise my own children in a similar fashion, especially my visually-impaired girl. Needless to say, I built on mom's successes.

MY TURN

"How are her eyes?" I slurred. I was fighting the paralyzing effect of anesthesia through 16 hours of labor pains, delivering my second child. My husband cleared his throat to conceal the truth. He said, "She'll be alright. You need to rest." I just knew then that my baby girl inherited aniridia, my visual impairment. The news pulled me into a vortex of fear for my child, denial, despair and utter darkness. There was no anesthesia for this heartache that left me dead inside for what felt like years.

THE WAKE UP CALL

"When in the dark, I follow my heart to the invisible light which only the heart can see."

"I have four, you only have one!" mom yelled back at me over the phone. "You yourself are visually impaired, so you have no excuse!" Mom's voice and wisdom shook me back to reality.

My trained response set me to work. My husband and I agreed on how we were to raise our daughter. We decorated Jem's crib with brightlycolored mobiles, anything that lit up and made a sound. I recruited my sighted son to constantly engage her in play and to assist her whenever she asked. I applied everything I learned from my life, school, and career. However, because I myself have no vision, I often felt that I fell short of imagination and resourcefulness to ensure that my little Jem would not be missing out on visual information vital to her development.

My husband, son and the community filled in for my perceived shortcomings. What's made this situation even more unique is the personality factor. Unlike my son, who has a steady disposition, Jem is either exploding with high-voltage energy, or withdrawn and moody. She knows what she wants and demands that every whim be accommodated. Often, emotions overtake my sensibilities, but Jem's infectious positive energy always sets me back on track. As most parents of a child with special needs will tell you, while there are burdens, there are also great sources of joy. Jem became class president in the 4th grade and was part of the student council in middle school. Except in Math and Science, the Waterloo of most students with disabilities, Jem consistently demon strated leadership and academic excellence. What about her conduct? Let's just say what I got was my own mom's payback for the pains I had caused her whenever she was called to the principal's office.

I stepped into my mother's shoes with the new era's gift of technology working to my family's advantage. Children's audiobooks, multi-sensory toys, time and labor-sa ving devices were available. When we moved to America, Jem was surrounded with Adaptive Technology. My son, who had become computer savvy, became key to digitizing information for his visually-impaired family. There were times when certain books and readings were not in a digital format and so, like my mom, I would stay up with Jem, in our case, helping her scan school materials through Kurzweil, a program which transcribed text to speech. Later, with the development of cell phones' accessibility features to magnify text, we would take a picture of each page of her required reading so that she'd be able to increase the font sizes and read comfortably. Technology afforded me the gift of time my mother never had.

As a mother, I mentored my daughter and her older brother to be introspective and self-directed, to know who they really are, and what they want to do and become in life. The best learning opportunities for my children came after they made the wrong choices or when they overlooked important things. When my son got into a bad accident as a new driver, I demanded that he write his learnings from the incident. When my daughter was bullied in her Junior Reserve Training Corps and she slapped the bully, I demanded from her a reflection paper. I would rarely get angry, but I was firm in requiring honest reflection papers.

Though my children hated these exercises, I always reiterated that to waste one's pains is the worst mistake. Negative feelings, I advised, are the sonar that detects issues of the heart that needed to be sorted out. It's funny how I developed a third eye (in my case my only eye) – a mother's extrasensory perception that enabled her to know what was going on with her children. I like to think, much like my own mother had.

IT ALL BEGAN WITH MOM

Deep in my thoughts during that memorable mother-daughter reunion years ago, I was interrupted by my mom's highpitched, forceful voice. "Who's going to take you to school today?" she asked. She never ceased to amaze me. Though her mental capabilities had diminished significantly, mom still remembered that when I was a young student, someone had to drive me to school. I teared up as I realized that a mother's heart had the will to continue caring and nurturing beyond illnesses and, through lessons passed down, beyond physical death.•

MOTHER AND CHILD REUNION: The author during a trip with daughter Jem (above left), and the three generations sharing a close moment (right). "As a mother, I mentored my daughter and her older brother to be introspective and self-directed, to know who they really are, and what they want to do and become in life."

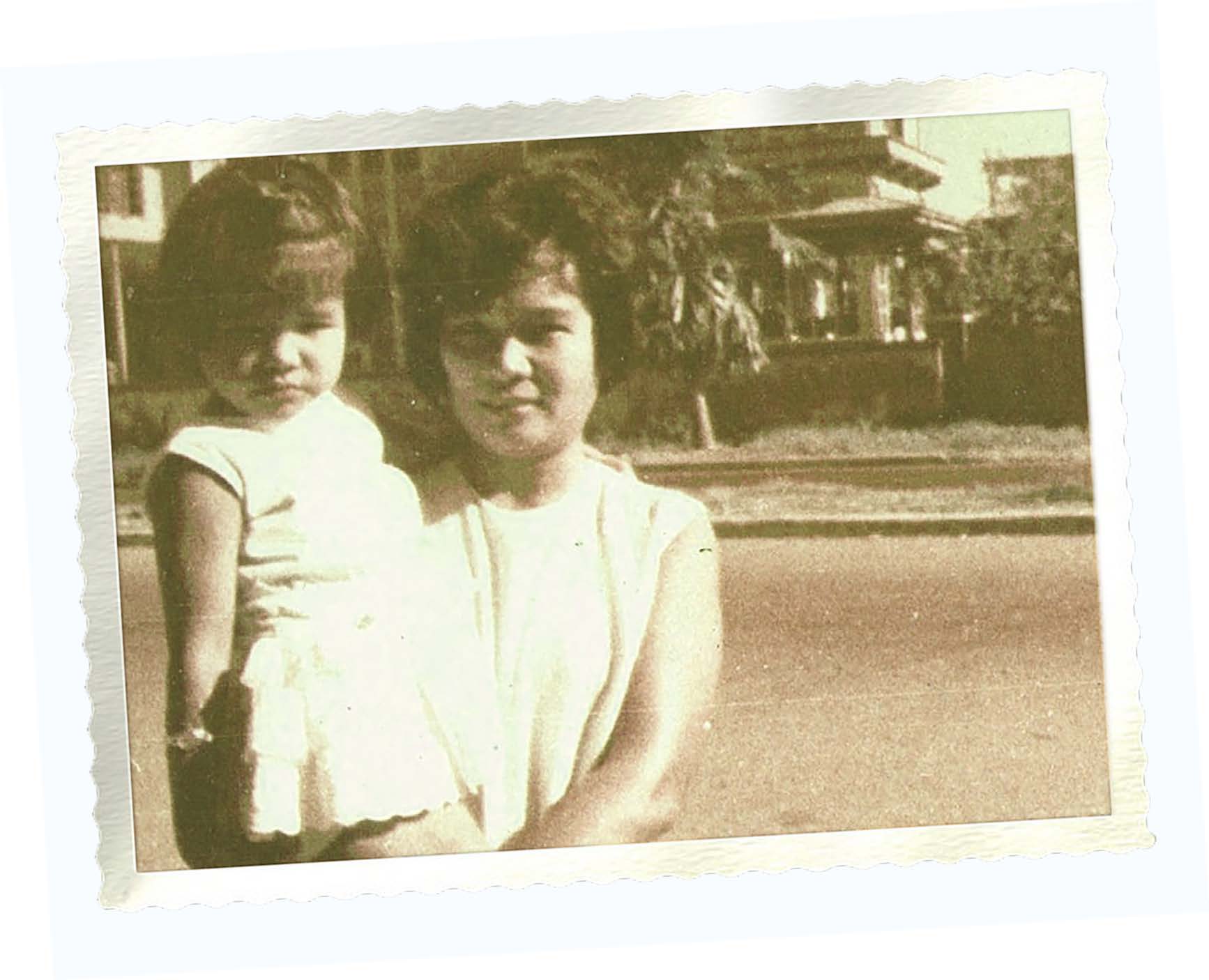

MOTHER KNOWS BEST: "What if my mother had not chosen to have more babies because her first child was visually impaired? With her choice to have us all, one could say the special needs community is a little better today."

HEARTSIGHT Christina Llanes Mabalot is physically blind from aniridia, but has a vision. She enjoys touching people's lives to bring out the best in them. "Heartsight" explains her ability to see with her heart. Christina earned her B.A. degree and Masters in Education from the University of the Philippines, Diliman, specializing in Early Intervention for the Blind. She later received Educational Leadership training through the Hilton-Perkins International Program in Massachusetts, then worked as consultant for programs for the VI Helen Keller International. She has championed Inclusive Education, Early Intervention, Capability Building and Disability Sensitivity programs. She was twice a winner in the International Speech contests of the Toastmasters International (District 75) and has been a professional inspirational and motivational speaker. Christina is blissfully married to Silver Mabalot, also physically impaired, her partner in advancing noble causes. Their children are Paulo and Jem, who has aniridia.