CHRISTINA LLANES MABALOT

Where It All Began

The noblest outcome of my physical blindness is that I've learned to perceive life and the world with my heart. While the heart is usually associated with love and warm fuzzy feelings, the deeper meaning of having heart is connecting one's physical state with something greater beyond ourselves, something that makes our heart beat.

I am the fourth of five children, four of whom have aniridia (underdeveloped iris) and have been legally blind since birth. Often kept in the house by our mindful parents, I didn't really realize that I was "different" and the ironic thing is that my only sighted sibling felt he was the quirky one.

One of the hardest decisions that my parents had to make revolved around our education. My overprotective father demanded that we go to a residential school for the blind. Anxious about what people would think about us, he said, "I don't want my kids to be mocked and ridiculed when they hold a book or paper next to their eyes when they read." In rebuttal, my mother said, "I don't want my kids to be any more different from most people than they already are."

In the 1960's, when mainstreaming was unheard of, my mother fought for us to be admitted in a private school for girls. Mainstreaming almost cost my parents' marriage.

My mother literally begged the nuns at the school to accept my oldest sister into kindergarten. Little did they know then that there would be three more visually-impaired children to follow. Thus, began the evolution of a visually-impaired student, blending into a sighted world.

It felt so different from home with the family wherein visually-impaired kids were the majority. Initially, I felt that family was my refuge and school would be my Waterloo. I grew up in a developing country, the Philippines, where educational services for children with disabilities at that time simply didn't exist. It was sink or swim for me which, it turned out, was good, because it taught me survival skills which saved me in numerous impossible situations. My touch typing skills were self-taught. Since I couldn't see the blackboard, I entreated seatmates to make carbon paper copies of Math and Science notes which my mom would later read to me at home. To make my seatmates feel good about the job, I'd call them my "execut i ve assistants."

Understanding my lessons took extra steps, and the tape recorder was my best friend. There were no short cuts. I once tried cheating in a Science quiz by asking my seatmate the answer, but our teacher caught me and was asked to stand at the back of the classroom facing the wall. So, I was determined never the to cheat again. Eventually I learned Braille through Hadley Correspondence Course and I availed myself of the services of the National Library of Congress' Talking Books Services. At the end of the day, however painful acade mic struggles were, I felt that hanging out with school friends was the best part of coming to school. I was convinced that the sighted world wasn't that bad after all.

I learned that to keep good friends, I had to be one. Early on, I yielded to the truth that attitude is everything – especially because there were those who acted blind-o-phobic, and the only way I could blend into the community was by being pro-active. Being a chatterbox with an incredible ability to laugh at the faintest sneeze made things easier for me. A stream of faux pas became a part of daily living and led to skill-sharpening. From those experiences I have collected a throve of the funniest stories ever told. If I learned how to keep a poker face while telling the funny stories, I'd be a wealthy stand-up comedian.

Laughter and optimism come in handy when facing barriers in the world out there, the biggest of which are cultural and social. Seemingly, the greatest advantage of being blind is to not "see" barriers. After all, "what is essential is invisible to the eye." All my life, most people would tell me, "You can't…" I couldn't "play with other kids because I might hurt myself… I couldn't attend a regular school because I wouldn't be able to cope…I couldn't get employed because I couldn't work… and, I wouldn't be able to get married because I couldn't be a wife and a mother…" Good thing I knew better than to be confrontational but still be able to demand for my rights. I had to feel my way through one obstacle at a time and prove that "he who overcomes is he who perseveres and believes he can."

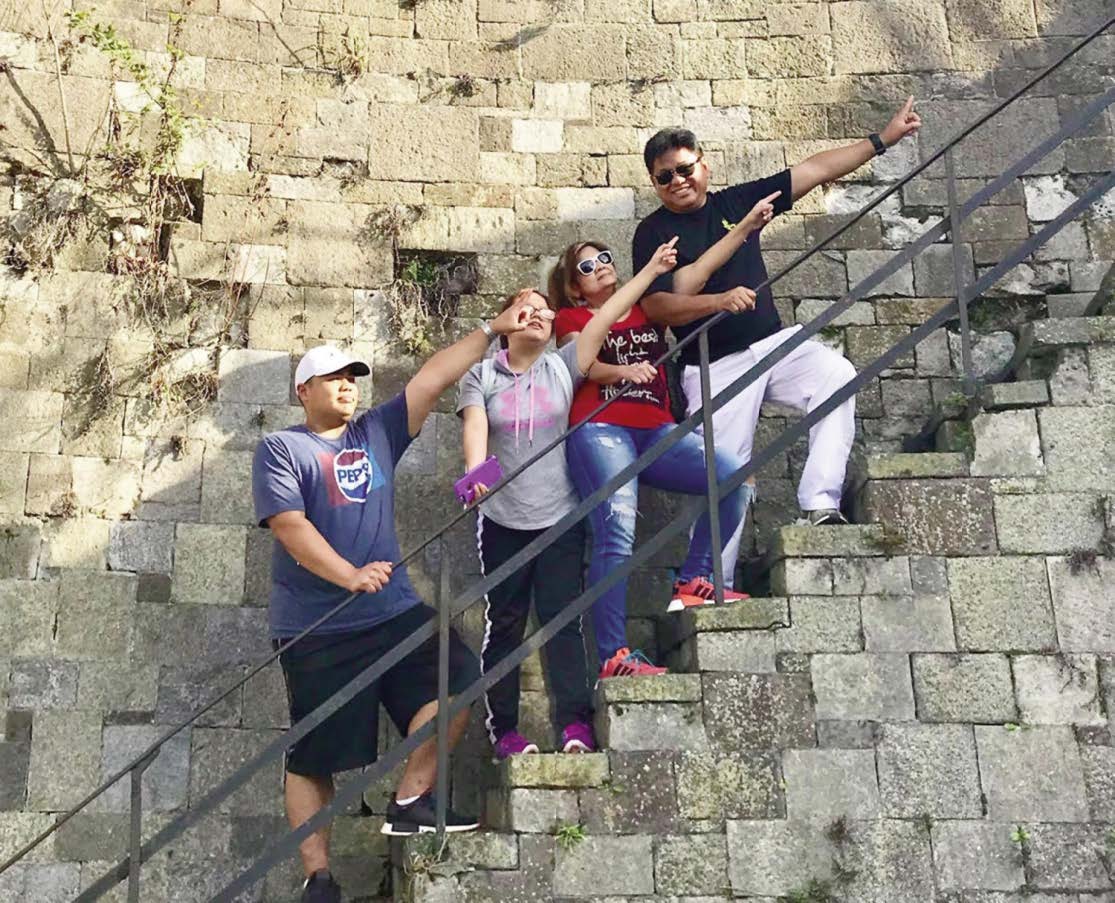

LOOKING UP: The Mabalot family (from left to right): Paulo, Jem, Christina and Silver. "The most valuable lesson I've learned through my condition is to live my life the way I want to – full of laughter, joy and endless jokes, which my family is absolutely fond of. Anyway, the world does not shut itself off from the blind, does it?"

In my obstacle-riddled life story, I have fallen and failed, I've been victorious and joyful, I've gained and lost relationships. All those times, I've learned how to bounce back because I believe that one's greatest obstacle might just be one's greatest miracle. One of my greatest miracles was raising my sighted son, Paulo, and our exploits together are part of a story best told for another day. I am proud to say that he is now is a Navy corpsman pursuing a career in Dentistry. My second great miracle is how the most wonderful sighted man stuck with me through almost 25 years of the oddest marriage.

The third miracle in my life involves my younger child, Jem, who is also visually impaired. Truth be told, the hardest thing in my life was, still is, and will always be having to endure the thought of Jem having aniridia. It is a million times harder for a mother who has suffered all the pains to know what her child has yet to discover. I fell into depression for some time when I learned of my daughter's special need. But, yet again, I bounced back and set out to conquer another course in my journey – what I call Life Application 101 – helping blend a visually-impaired child into the community. This has included making sure the sighted child (my son) is given as much attention as the child with disability – a painful lesson I learned growing up and witnessing my sighted brother turn bitter from the lack of my parents' attention.

Yet another miracle in my life: this year, my visually-impaired daughter is graduating college with an International Studies degree. Despite her disability, she has always been a diligent A student. As a mother who understands deeply how my daughter goes through life, I want her to be free and independent. She lived in Japan for a year as an exchange student and, following college, is aiming to work there as a coordinator for International Relations. The most valuable lesson I've learned through my condition is to live my life the way I want to – full of laughter, joy and endless jokes, which my family is absolutely fond of. Anyway, the world does not shut itself off from the blind, does it?

The noblest outcome of my physical blindness is that I've learned to perceive life, and the world, with my heart. While the heart is usually associated with love and warm, fuzzy feelings, the deeper meaning of having heart is connecting one's physical state with some t hing greater beyond ourselves, something that makes our heart beat. Once upon a time, my heart was blind too, because I was focused on my physical blindness! It was bad enough to be physically blind but, alas, it would've been more unfortunate to also be blind in one's heart. Why? All the issues of life spring from the heart.

Oh, how my heart desperately needed to be recreated to see right! As I labored through life's challenges, I birthed a transformed heart. "Heartsight" is what I call seeing with my heart. •

TRUE BLUE: The author with her sighted son, Paulo, now a Navy corpsman pursuing a career in Dentistry.

HEARTSIGHT

Christina Llanes Mabalot is physically blind from aniridia, but has a vision. She enjoys touching people's lives to bring out the best in them. "Heartsight" explains her ability to see with her heart. Christina earned her B.A. degree and Masters in Education from the University of the Philippines, Diliman, specializing in Early Intervention for the Blind. She later received Educational Leadership training through the Hilton-Perkins International Program in Massachusetts, then worked as consultant for programs for the VI Helen Keller International. She has championed Inclusive Education, Early Intervention, Capability Building and Disability Sensitivity programs. She was twice a winner in the International Speech contests of the Toastmasters International (District 75) and has been a professional inspirational and motivational speaker. Christina is blissfully married to Silver Mabalot, also physically impaired, her partner in advancing noble causes. Their children are Paulo and Jem, with aniridia.